CAIRO | It’s an ancient worry facing a modern challenge.

Anxiety over water is growing in Egypt as Ethiopian leaders press forward with plans to build a massive dam that officials here fear will block the flow of the Blue Nile.

Addis Ababa started construction of the massive Grand Ethiopian Renaissance Dam in 2011 when Egypt’s leaders were consumed with the Arab Spring uprising that ousted longtime President Hosni Mubarak.

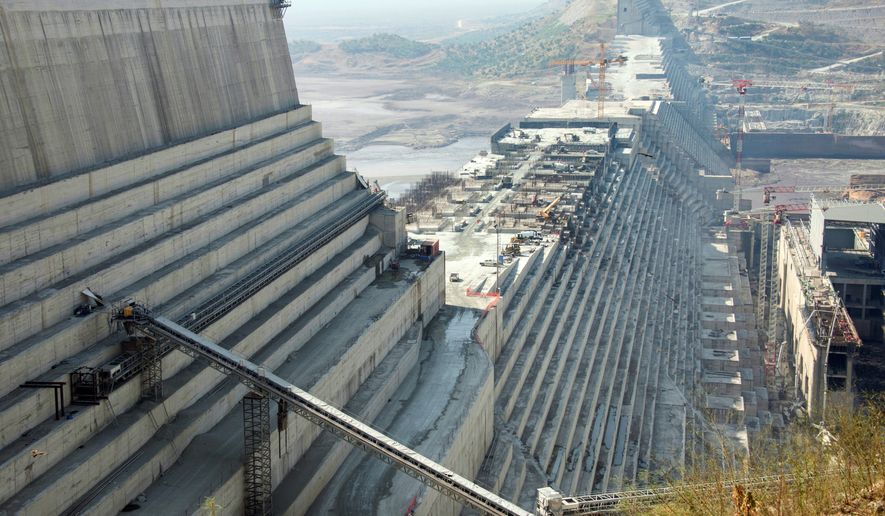

Slated for completion in 2022 — four years behind schedule — the $4.8-billion-dollar dam would be the seventh-largest dam in the world and Africa’s largest hydroelectric power plant. That makes it a priority for Ethiopian leaders despite the worries of downriver countries that depend heavily on the Nile.

“It’s one of the most important flagship projects for Ethiopia,” said Seleshi Bekele, the country’s minister of water, irrigation and electricity.

But the 510-foot-tall, 5,840-foot-long structure would give Ethiopia control over the headwaters of the Blue Nile, the source of 80 percent of Egypt’s water.

Egyptian concerns about potential water shortages have put the regional powers at loggerheads, said Mustafa Kamal, an analyst at the government-affiliated Al Ahram Center for Political and Strategic Studies in Cairo.

“The negotiations have been sputtered, and diplomats have not made any progress for almost nine years because Ethiopia will not back down from filling the reservoir and continues to move forward with the project without considering the concerns of the Egyptian side,” Mr. Kamal said.

Egyptian officials insist that international agreements signed in 1929 and 1959 give Egypt rights to 55.5 billion cubic meters of Nile water per year. Sudan, which lies between the two countries, receives 18.5 billion cubic meters annually under the agreements. The Blue and White Nile Rivers combine in Sudan, forming the Nile River that empties into the Mediterranean Sea.

Those agreements also gave Egypt a veto on any projects proposed on the river. Egyptians are angry that Ethiopia moved forward in 2011 without consulting them.

“It was upsetting to see the last Ethiopian prime minister take advantage of the chaos in Egypt to push ahead with this project at a time he knew there could be no consultation with anyone in Cairo,” said Ahmed Noubi, who owns a sugar cane farm south of Luxor.

The timetable for filling the reservoir is the most critical problem for Egypt. The faster Ethiopia fills the dam, the less water will flow to Egypt and Sudan. Ethiopia theoretically could fill the reservoir to full capacity in three years. But Egypt is insisting on a more extended timetable of up to a decade to ease the transition.

Egypt is already near the U.N. threshold of water poverty, providing just 660 cubic meters of water per capita annually. The United Nations calls it one of the most water-stressed nations on the planet.

“In light of the continuous population increase in Egypt, it is certain that we will face many difficulties and a water disaster is in store during the period that Ethiopia fills the dam reservoir,” Mr. Kamal said.

Dire projections

With the Nile supplying 97 percent of Egypt’s water needs, the situation could grow dire in a relatively short time, according to a report released in March by the Geological Society of America.

“With a population expected to double in the next 50 years, Egypt is projected to reach a state of serious countrywide fresh water and energy shortage by 2025,” the geological society said.

Cairo traditionally has taken a stern view of any effort by upstream nations to moderate the flow of the Nile, Tobias von Lossow, a specialist on dams at the Netherlands Institute of International Relations, told the online news site Middle East Eye last week. But the political turmoil in Cairo in recent years provided an unexpected opening.

“Along came Ethiopia and, against all the odds and the doubts of many outsiders, including the Egyptians, the GERD has been built,” said Mr. von Lossow, noting that Sudan has sided with Ethiopia in the standoff.

Ethiopian leaders insist that the dam is necessary to power their fast-growing economy. Three-quarters of the country lacks electricity.

“It’s not about control of the flow but providing opportunity for us to develop ourselves through energy development,” said Mr. Bekele. “It has a lot of benefit for the downstream countries.”

Mr. Noubi responded by saying, “Ethiopia has a right to electricity, but they could have built a series of smaller dams and we would not be looking at years of drought as they fill the huge reservoir behind the Grand Renaissance Dam.”

The dispute could prove a foreign policy test for Ethiopian Prime Minister Abiy Ahmed, who won strong reviews after taking office in April with promises to tackle corruption, widen the political process and ease a bitter border standoff with Eritrea. Mr. Ahmed met with Egyptian President Abdel-Fattah el-Sissi in June to try to assuage Cairo’s concerns.

Mr. Ahmed also inherited a dam project dogged by scandals in the past year.

In May, a Nigerian executive and two employees of the company providing cement for the dam died in a roadside shooting as they were driving to Addis Ababa. The project’s former chief engineer, Simegnew Bekele, was found shot dead inside his car in July. About the same time, inspectors found defects in power turbines installed by the Metal and Engineering Corp., a company owned by Ethiopia’s military.

The Egyptian public has reveled in the setbacks.

“Allah is generous. This is a gift from God to the Egyptians,” popular TV talk show host Amr Adib said recently. “I tell our brothers in Ethiopia take your time and be patient, no hurry. Even better, dismantle the whole dam. We can send you engineers from here to do it.”

Despite the delays, Cairo has enacted stringent water-saving measures in anticipation of drier times to come.

Mr. el-Sissi late last month inaugurated several greenhouse projects with the ambitious aim of increasing Egypt’s agricultural output fourfold while reducing water consumption by about 60 percent. In October, the Egyptian Ministry of Housing, Utilities and urban Communities signed a contract with the U.S.-based Fluence Corp. to build three small seawater desalination plants for $7.6 million. Mr. el-Sissi has reduced water use in fields growing rice and sugar cane, two staples of local agriculture.

“I think the government is trying to do its very best,” said Hany Hamroush, professor of geology and geochemistry at the American University in Cairo.

Mr. Hamroush said he is worried about how Egypt will replace water that the dam might restrict but also is concerned about the stability of the dam, which lies near a fault line.

“Recent studies indicate that the rate of accumulation of mud in the reservoir behind the dam can be really very high and that eventually a huge amount of sediments can accumulate,” said Mr. Hamroush. “The accumulation of mud will exert real pressure on the base of the dam. This will make it a risk factor if, God forbid, there is an earthquake.”

Please read our comment policy before commenting.