He may have been overshadowed at times by the man whose crown he took, but former Russian world titleholder Vladimir Kramnik will go down in the annals of chess history as a class act, an underrated fighter and one of the most complete players to ever play the game.

Kramnik, who announced his retirement from competitive play last week at the relatively young age of 43, will be forever linked to compatriot Garry Kasparov, who first plucked the 16-year-old grandmaster from a Black Sea backwater town for the gold medal-winning 1992 Russian Olympiad team. The recruit would go on to beat the mentor in a memorable 2000 world title match in London, handing Kasparov — whom many consider the greatest ever — the only match loss of his fabled career.

Kramnik would hold the crown for seven years before finally being dethroned by India’s Viswanathan Anand. Despite battling health problems, Kramnik was one of the world’s top three players for nearly two decades, with a vast hoard of tournament victories, match wins and Olympiad and World Cup success. He’s also built a nice sideline as perhaps the best blindfold chess player of his era.

He was widely respected as a super-solid adversary, a defensive maestro who displayed his attacking chops only when necessary. But Kramnik also had an unexpected flair for the dramatic: His win over Kasparov was a masterpiece of match strategy and he retained his title in 2004 against Hungarian challenger Peter Leko by dint of a heart-stopping, must-win final game to knot the contest at 7-7.

It’s one of the most famous games of the new century and for good reason: Kramnik finds a way to keep his winning chances alive even as more pieces come off the board and his opponent seems perpetually on the verge of a match-clinching draw. Leko’s questionable opening choice allows White to achieve a dynamic, unbalanced position, and Kramnik hems in Black’s bishop with 18. Rac1! (a brave move allowing even more trades with the queens already off the board, but White banks on his knight outplaying the Black bishop) h5 19. Rhg1 Bc6 20. gxh5 Nxh5 21. b4 a6 22. a4!, when 22…Bxa4?! 23. Rc7 Rb8 (b5 24. Ke3 0-0 25. Rg5 g6 26. Bxg6!) 24. Ng5 0-0 25. Ke3 Bc6 26. Be2 g6 27. Bxh5 gxh5 28. Nxe6+ is great for White.

With 25. b6!, White secures the c7-square for his rook and the asphyxiation strategy works to perfection on 34. f4!! (a title-saving move; Black’s king is boxed in and White just needs one more attacker for the kill) Ra2+ (Rxd4 35. f5! exf5 36. e6 Re4+ 37. Nxe4 dxe4 38. Rc7, and if 38…f4, 39. Rxc6! bxc6 40. b7 Kc7 41. e7 wins) 35. Kf3 Ra3+ 36. Kg4 Rd3 37. f5! Rxd4+ 38. Kg5 (a Capablanca-like endgame, shedding pawns to win decisive tempi) exf5 39. Kf6 Rg4 40. Rc7 Rh4 41. Nf7+, and Leko conceded facing 41…Ke8 42. Rc8+ Kd7 43. Rd8 mate.

Dignified to the end, Kramnik is stepping away from the game he enriched for so long on his own terms.

“The life of a professional chess player was a great journey and I am very thankful to chess for all it has given me,” he said in a statement at the end of the recent Tata Steel Chess tournament in the Netherlands, adding he still might play in occasional blitz or rapid event.

“But I have also expressed in interviews before that I would like to try doing something else one day, and since my chess player motivation has dropped significantly in recent months, it feels like the right moment for it. I would like to concentrate on projects which I have been developing during the last months especially in the field of chess for children and education.”

—-

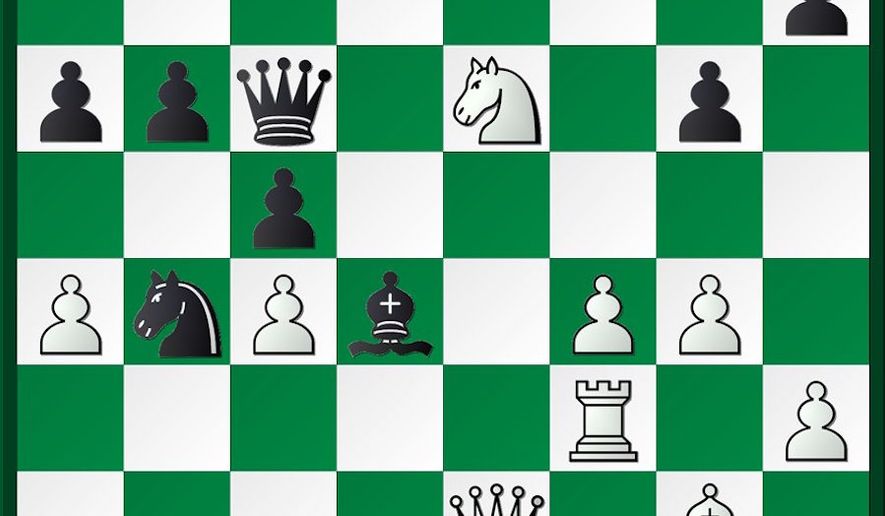

With Kramnik stepping aside, the hunt is on for what one wag called the NGV — the “next great Vlad.” Twenty-year-old Omsk GM Vladislav Artemiev may have the inside track with his surprise win at the 2019 Gibraltar Chess Festival last week over a world-class field. He got a big boost with a Round 7 upset of U.S. star Hikaru Nakamura, which we pick up from today’s diagram.

The tension gets to both players before Black commits the fatal mistake: 27. f5!? Qxa4 28. fxg6 Rxf3 29. gxh7+ Kh8?! (with silicon sangfroid, the computer prefers 29…Kxh7 30. Qe4+ Kh8 31. Qxf3 Kg8 32. Nxd4 Re3! 33. Qxe3 [Qa8+ Re8 is equal] Qxd1+ 34. Kh2 Qxd4) 30. Bxf3? (better was 30. Qxf3!, when 30…Rxe6 loses to 31. Qf8+ Kxh7 32. Rf1 Bg7 33. Qf5+ Rg6 34. Be4 Qe8 35. Qh5+ Bh6 36. Bxg6+ Qxg6 37. Rf7+!) Nc6?? (meeting the threat of 31. Rxd4 cxd4 32. Qe5+, but walking into another shot) 31. Nxc5!, and Black resigned because of 31…Rxe2 32. Nxa4 (the Black rook and knight hang and the bishop is loose, too) Rc2 (Re6 33. Bxc6 Rxc6 34. Rxd4) 33. c5! (far less convincing is 33. Bxc6? Rxc4 34. Bd7 b5 35. Bxf5 Rxa4) bxc5 34. Bxc6 and wins.

Kramnik-Leko, World Championship Match, Game 14, Brissago, Switzerland, October 2004

1. e4 c6 2. d4 d5 3. e5 Bf5 4. h4 h6 5. g4 Bd7 6. Nd2 c5 7. dxc5 e6 8. Nb3 Bxc5 9. Nxc5 Qa5+ 10. c3 Qxc5 11. Nf3 Ne7 12. Bd3 Nbc6 13. Be3 Qa5 14. Qd2 Ng6 15. Bd4 Nxd4 16. cxd4 Qxd2+ 17. Kxd2 Nf4 18. Rac1 h5 19. Rhg1 Bc6 20. gxh5 Nxh5 21. b4 a6 22. a4 Kd8 23. Ng5 Be8 24. b5 Nf4 25. b6 Nxd3 26. Kxd3 Rc8 27. Rxc8+ Kxc8 28. Rc1+ Bc6 29. Nxf7 Rxh4 30. Nd6+ Kd8 31. Rg1 Rh3+ 32. Ke2 Ra3 33. Rxg7 Rxa4 34. f4 Ra2+ 35. Kf3 Ra3+ 36. Kg4 Rd3 37. f5 Rxd4+ 38. Kg5 exf5 39. Kf6 Rg4 40. Rc7 Rh4 41. Nf7+ Black resigns.

• David R. Sands can be reached at 202/636-3178 or by email dsands@washingtontimes.com.

• David R. Sands can be reached at dsands@washingtontimes.com.

Please read our comment policy before commenting.