OPINION:

In a 2008 case called District of Columbia v. Heller, and again in a 2010 case called McDonald v. City of Chicago, the U.S. Supreme Court definitively interpreted the Second Amendment.

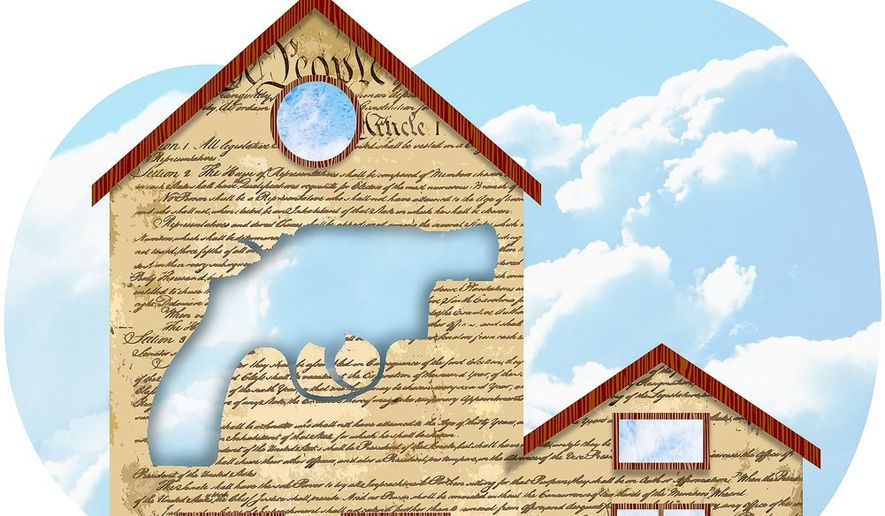

That amendment was written, the court ruled in both cases, to mandate the obligation of the federal government, as well as cities and states, to recognize, respect and permit the exercise of the right to self-defense, using the same level of technology as might be used against someone in the home. Stated differently, the high court twice held in the past 11 years that the right to own and keep and — if necessary — to use a gun in the home is a personal pre-political right.

“Pre-political” has a long and fascinating history. Its literal meaning is that whatever it is describing — here, the right to own a gun — pre-existed the political order. It pre-existed the government and the U.S. Constitution. So, where did it come from? That’s like asking where free thought and free speech came from. The right to self-defense is a natural human right, like thought and speech. We cannot be complete human beings enjoying life and liberty and pursuing happiness without the right to repel those who would harm us.

The court also ruled that the Second Amendment would be meaningless if it failed to protect the right to own and use weapons for self-defense of the same level of sophistication as an adversary — whether agents of a tyrant or a mob of thugs or a deranged killer.

One would expect that cities and states should have enacted laws to facilitate the exercise of that right. Instead, many have done the opposite, and none as absurd as New York City. There, the government enacted a bizarre ordinance that prohibited lawful gun owners from transporting their guns to any place outside city limits. The practical effect of such a law prohibited the transportation of an unloaded gun to a shooting range or gun shop or private home outside the city. It also forced those gun owners who wished to remain skilled in the use of guns to practice their use only at any of three dingy, poorly equipped and out-of-the-way gun ranges in the Bronx.

A group of New York City gun owners challenged the law as a material interference with their Second Amendment rights. Some of the owners had second homes in New Jersey and elsewhere in New York state where the ownership of their New York City-licensed guns is legal, but they could not lawfully transport their guns out of New York City.

After the ordinance challenge failed in a federal district court and again in a federal appellate court in Manhattan, the gun owners asked for permission to appeal to the Supreme Court, which was granted. Then the city, fearing a reversal and invalidation of its ordinance, repealed the ordinance and enacted a new one in its place. The new ordinance permitted transportation of New York City-licensed guns to places outside of the city where the guns are lawful, but required the owners to transport them there without stopping, in one complete trip. Can one stop for coffee, or for nature, or to visit mom? No.

Does any of this sound as if the government of New York City recognizes and respects the right to keep and bear arms? Of course not. So, why did the city change its gun ordinance? Why did it give the gun owners at the last minute before their case was to be heard almost all they sought? Because of the doctrine of “standing.”

“Standing” is a constitutional requirement of the existence of real adversity between litigants. Federal courts do not hear theoretical cases. They are required by the Constitution to hear cases and controversies in which the moving party can show that real harm has been caused by the responding party.

So, at the time of oral argument in the Supreme Court earlier this week, there was no such adversity between the gun owners and the city because the ordinance that the owners challenged no longer exists. Thus, the city asked the court to dismiss the appeal. Under usual circumstances, the court would do so.

In a famous New Jersey case, the lawyers finished oral argument before the Supreme Court and on their way out of the courthouse settled the case. That quick and amicable settlement divested the court of jurisdiction over the case because there was no longer a controversy and no one had standing to bring the appeal.

Will the New York City gun owners suffer the same fate? Perhaps not. There is a little-known and rarely used exception to the standing requirement — a judge-made exception — which holds that if a dispute repeatedly comes to the Supreme Court or if lower federal courts are repeatedly misinterpreting a Supreme Court decision, the Supreme Court will hear an appeal to stop the repeated appeals or to correct lower court misunderstandings, even if there is no adversity between the parties.

Have lower federal courts been misinterpreting the Heller and McDonald cases? Yes. By one study, they have ruled 96 percent of the time in favor of city and state gun restrictions in the home and against the pre-political nature of the right to self-defense.

Are there constitutional implications in this case beyond standing? Yes. Heller and McDonald uphold the right to keep and bear arms only in and around one’s home. If the gun owners in this New York City case prevail, that right could be extended to public places outside the home, where police acknowledge that armed and well-trained civilians are most valued today. Even New York City would need to respect that.

• Andrew P. Napolitano, a former judge of the Superior Court of New Jersey, is a regular contributor to The Washington Times. He is the author of nine books on the U.S. Constitution.

Please read our comment policy before commenting.