Hillary Clinton operatives fed the FBI false information on President Trump and his aides in the months following his election, according to an analysis of an FBI agent’s interview with a key conduit.

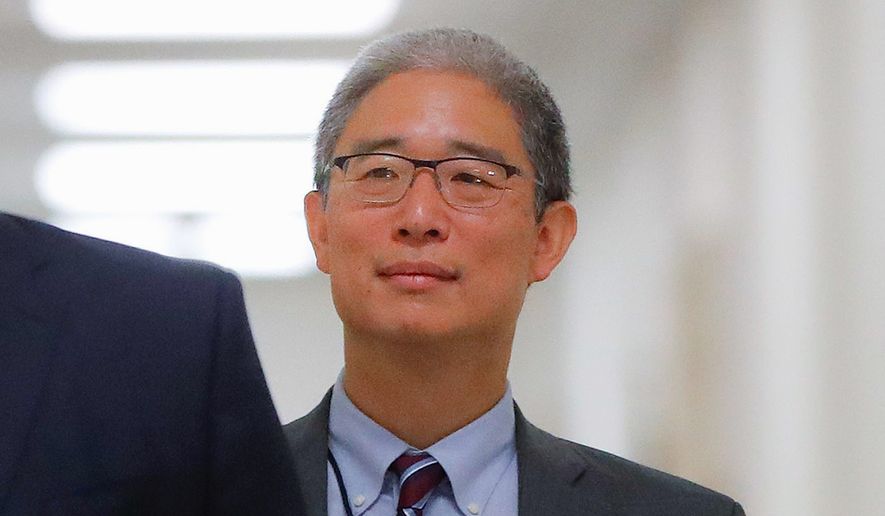

The agent’s interview notes (known as 302s) of Bruce Ohr, then an associate deputy attorney general in the Department of Justice, were obtained by the conservative investigative group Judicial Watch.

“These new Bruce Ohr FBI 302s show an unprecedented and irregular effort by the FBI, DOJ, and State Department to dig up dirt on President Trump using the conflicted Bruce Ohr, his wife, and the Clinton/DNC spies at Fusion GPS,” said Judicial Watch President Tom Fitton.

The 302s show Mr. Ohr regularly funneled material from Fusion GPS and its agent, ex-British intelligence officer Christopher Steele, directly to the heart of FBI headquarters, which was investigating Trump associates. Both Fusion GPS and Mr. Steele were paid with money from the Clinton campaign and the Democratic National Committee.

The final report of former special counsel Robert Mueller didn’t delve into the roles of Fusion GPS and Mr. Steele in framing the FBI investigation into a supposed Trump-Russia election conspiracy. Mr. Mueller said in March that his 22-month probe he didn’t uncover a conspiracy.

A Washington Times review of the Mueller report compared with Mr. Ohr’s 302s showed he was peddling false information. The FBI notes say that agents accepted Fusion material as official evidence.

For example, Mr. Ohr, conveying information from Mr. Steele and Fusion co-founder Glenn Simpson, told of a secret dedicated server at Trump Tower connected to Alfa Bank. Alfa is Russia’s largest commercial bank, run by an oligarch close to President Vladimir Putin.

The existence of such a server would be possible evidence of collusion. Mr. Mueller’s Justice Department written mandate told him to investigate “any links” between a Trump ally and Russia.

But Mr. Mueller’s report, while discussing Alfa Bank post-election efforts, makes no mention of a dedicated server. Mr. Mueller debunked the server tale during testimony last month before the House Permanent Select Committee on Intelligence.

Mr. Ohr also told his FBI handler that Sergei Millian, a Belarus-born U.S. citizen, used the server to communicate with the Kremlin.

“Millian may have overseen many financial transfers from Russia to assist the Trump campaign,” Mr. Ohr quoted Mr. Simpson as saying.

The Mueller report mentions Mr. Millian’s efforts to form professional ties with Trump campaign volunteer George Papadopoulos. But there the narrative ends. There is no description of any Millian-Trump-Russia financial ties.

Mr. Ohr also told the FBI that Michael Cohen, then Mr. Trump’s attorney, had become the messenger for a conspiracy with the Kremlin. He said Cohen replaced campaign adviser Carter Page and campaign manager Paul Manafort.

There is no evidence in the Mueller report that Manafort or Mr. Page knew each other or worked as election collusion conspirators.

Likewise, Cohen isn’t described as someone in a Kremlin election conspiracy, for which no Trump colleague was ever charged.

Some of Mr. Ohr’s actions were known through his testimony to a House task force last year.

But the 34 pages of 302s underscore how Mr. Ohr, an agent for Fusion and thus a Clinton operative, gained access to FBI decision-makers in 2016-17. He fed the bureau a steady diet of conspiracies as agents surveilled Trump allies. Mr. Ohr said he knew that Fusion allegations were being delivered to the Clinton campaign.

He delivered two tranches of anti-Trump data to the FBI via thumb drives. One was Mr. Steele’s numerous allegations against Mr. Trump, whom he was “desperate” to destroy. The other came from Mr. Ohr’s wife, Nellie, who worked at Fusion as a Russia expert. Both databases became official FBI evidence.

The 302s, acquired by Judicial Watch through an open records lawsuits, are heavily redacted. There appears to be a discussion about Mr. Steele’s sources.

In his infamous and discredited dossier, Mr. Steele says his information came from Kremlin intelligence sources. Republicans argue that the dossier amounts to foreign interference by the Clinton campaign into a U.S. election.

Mr. Ohr continued to speak with Mr. Steele, via phone calls, emails and Whatsapp, even though the FBI fired the intelligence contractor in October 2016 for talking to the press. At one point, the FBI had decided to pay Mr. Steele $50,00 to continue investigating Mr. Trump and his presidency.

Mr. Steele had not given up on reviving a deal.

By February 2017, as the Ohr-FBI relationship continued, Mr. Ohr said Mr. Steele worried about his private investigative business. He was preparing some type of proposal “to broker a business relationship with the FBI,” the 302 said.

“You may see me re-emerge in a couple of weeks,” he told Mr. Ohr.

Mr. Steele was “pleased about” a CNN article that said “U.S. government investigation had confirmed some of the reporting on his dossier.”

CNN regularly pushed the Trump-Russian conspiracy story for months.

But the government didn’t confirm any of Mr. Steele’s conspiracy allegations.

A month earlier, in a blow to Mr. Steele’s desire to shroud his work in secrecy, BuzzFeed posted his entire dossier. The press, with whom he was working so closely as a confidential source, outed him as the author.

Mr. Steele did gain new employment. According to a separate FBI document, he was hired by a former staffer for Sen. Dianne Feinstein, California Democrat, to keep investigating Mr. Trump.

By May, Mr. Ohr was negotiating to bring the FBI and Mr. Steele back together.

In early July 2016, an FBI agent visited Mr. Steele at his England home. The agent received a briefing on Mr. Steele’s shocking Trump-Russia allegations. The agent said he was taking them directly to headquarters.

Later, agents met with Mr. Steele in Rome.

Mr. Steele also briefed State Department officials during the Obama presidency. Other surrogates briefed the White House.

• Rowan Scarborough can be reached at rscarborough@washingtontimes.com.

Please read our comment policy before commenting.