OPINION:

When the Department of Justice designated Robert Mueller as special counsel to take over the FBI investigation of the Trump campaign in May 2017, Mr. Mueller’s initial task was to determine if there had been a conspiracy — an illegal agreement — between the campaign and any Russians to receive anything of value.

When former FBI Director James Comey informed Mr. Mueller that he believed Mr. Trump fired him because he had declined Mr. Trump’s order to shut down the investigation of Mr. Trump’s campaign and of his former national security adviser, retired Lt. Gen. Michael Flynn, Mr. Mueller began to investigate whether the president had unlawfully attempted to obstruct those investigations.

We now know why Mr. Trump was so anxious for the FBI to leave Flynn alone.

Flynn was charged and pleaded guilty to lying to the FBI about whether he discussed sanctions in a telephone call with then-Russian Ambassador to the United States Sergey Kislyak, before Mr. Trump became president. Such a communication could have been unlawful if it interfered with American foreign policy.

So, when Mr. Trump learned of the lie, he fired Flynn. Yet, in his plea negotiations with Mr. Mueller, Flynn revealed why he discussed sanctions with Mr. Kislyak — because the pre-presidential Mr. Trump asked him to do so. An honest revelation by Mr. Trump could have negated Flynn’s prosecution. But the revelation never came.

Last week, Attorney General William Barr released publicly a redacted version of Mr. Mueller’s final report. That report concluded that notwithstanding 127 confirmed communications between the campaign and Russians from July 2015 to November 2016 (Mr. Trump said there were none), the government could not prove the existence of a conspiracy.

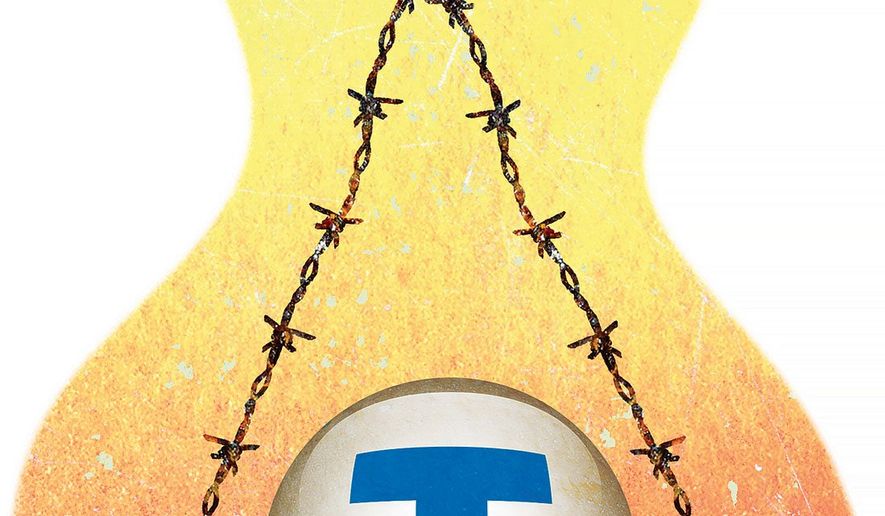

On obstruction, the report concluded that notwithstanding numerous obstructive events engaged in by the president personally, the special counsel would not charge the president and would leave the resolution of obstruction of justice to Congress. Congress, of course, cannot bring criminal charges, but it can impeach.

Mr. Trump initially claimed that he had been completely exonerated by Mr. Mueller — even though the word “exoneration” and the concept of DOJ exoneration are alien to our legal system. Then, after he learned of the dozen or so documented events of obstruction described in the report, Mr. Trump used a barnyard epithet to describe it.

The U.S. Constitution prescribes treason, bribery or other high crimes and misdemeanors as the sole bases for impeachment. We know that obstruction of justice constitutes an impeachable offence under the “high crimes and misdemeanors” rubric because both presidents in the modern era who were subject to impeachment proceedings — Richard Nixon and Bill Clinton — were charged with obstructing justice.

Obstruction is the rare crime that is rarely completed. Stated differently, the obstructer need not succeed in order to be charged with obstruction. That’s because the statute itself prohibits attempting to impede or interfere with any government proceeding for a corrupt or self-serving purpose.

Thus, if my neighbor tackles me on my way into a courthouse in order to impede a jury from hearing my testimony and, though delayed, I still make it to the courthouse and testify, then the neighbor is guilty of obstruction because he attempted to impede the work of the jury that was waiting to hear me.

Mr. Mueller laid out at least a half-dozen crimes of obstruction committed by Mr. Trump — from asking K.T. McFarland to write an untruthful letter about the reason for Flynn’s chat with Mr. Kislyak, to asking Corey Lewandowski and then Don McGahn to fire Mr. Mueller and Mr. McGahn to lie about it, to firing Mr. Comey to impede the FBI’s investigations, to dangling a pardon in front of Michael Cohen to stay silent, to ordering his aides to hide and delete records.

The essence of obstruction is deception or diversion — to prevent the government from finding the truth. To Mr. Mueller, the issue was not if Mr. Trump committed crimes of obstruction. Rather, it was if Mr. Trump could be charged successfully with those crimes.

Mr. Mueller knew that Mr. Barr would block an indictment of Mr. Trump because Mr. Barr has a personal view of obstruction at odds with the statute itself. Mr. Barr’s view requires that the obstructer have done his obstructing in order to impede the investigation or prosecution of a crime that the obstructer himself has committed. Thus, in this narrow view, because Mr. Trump did not commit the crime of conspiracy with the Russians, it was legally impossible for Trump to have obstructed the FBI investigation of that crime.

The nearly universal view of law enforcement, however, is that the obstruction statute prohibits all attempted self-serving interference with government investigations or proceedings. Thus, as Georgetown Professor Neal Katyal recently pointed out, former Detroit Mayor Kwame Kilpatrick was convicted of obstruction for interfering with an investigation of his extramarital affair, even though the affair was lawful.

Famously, Martha Stewart was convicted of obstruction of an investigation into her alleged insider trading, even though the insider trading charges against her had been dismissed. And a federal appeals court recently upheld the obstruction conviction of a defendant who suborned perjury in order to impede the prosecution of the sister of a childhood friend.

On obstruction, Mr. Barr is wrong.

So, the dilemma for House Democrats now is whether to utilize Mr. Mueller’s evidence of obstruction for impeachment. They know from history that impeachment only succeeds if there is a broad, national, bipartisan consensus behind it, no matter the weight of the evidence or presence of sophisticated legal theories.

They might try to generate that consensus by parading Mr. Mueller’s witnesses to public hearings, as House Democrats did to Nixon. Yet, when House Republicans did that to Mr. Clinton, and then impeached him, they suffered politically.

The president’s job is to enforce federal law. If he had ordered its violation to save innocent life or preserve human freedom, he would have a moral defense. But ordering obstruction to save himself from the consequences of his own behavior is unlawful, defenseless and condemnable.

• Andrew P. Napolitano, a former judge of the Superior Court of New Jersey, is a regular contributor to The Washington Times. He is the author of nine books on the U.S. Constitution.

Please read our comment policy before commenting.