OPINION:

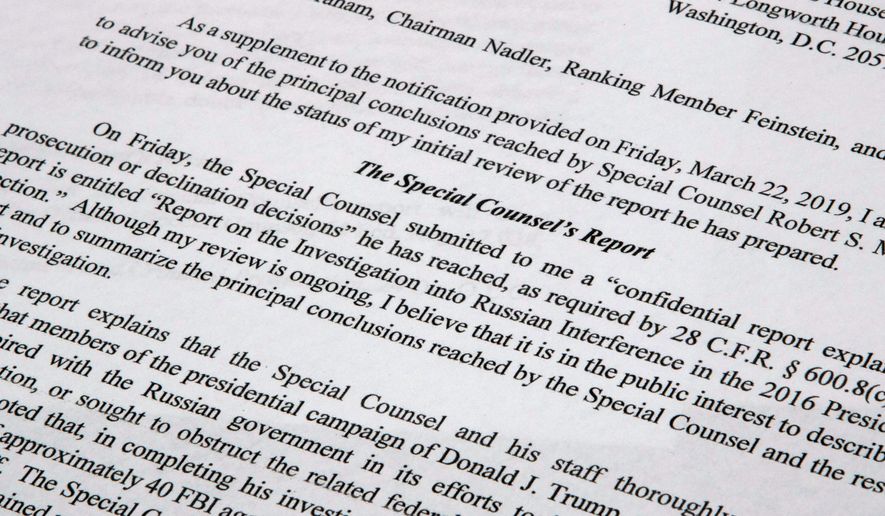

When Attorney General William Barr released his four-page assessment of Special Counsel Robert Mueller’s 400-page report, I was disappointed at many of my colleagues who immediately jumped on board the “no collusion” and “no obstruction” and “presidential exoneration” bandwagons.

As I write, Mr. Barr and his team are scrutinizing the Mueller report for legally required redactions. These include grand jury testimony about people not indicted — referred to by lawyers as 6(e) materials — as well as evidence that is classified, pertains to ongoing investigations or the revelation of which might harm national security.

Mr. Mueller impaneled two grand juries, one in Washington, D.C., and the other in Arlington, Virginia. Together, they indicted 37 people and entities for violating a variety of federal crimes. Most of those indicted are Russian agents in Russia who have been charged with computer hacking and related crimes in an effort to affect the 2016 presidential election. They will never be tried.

Some of the Americans indicted have pleaded guilty to lying to FBI agents, such as retired Lt. Gen. Michael Flynn, Rick Gates and George Papadopoulos. Papadopoulos told me personally that even though he pleaded guilty to lying to the FBI, he did not in fact lie to them. Do the innocent ever plead guilty? Answer: Yes, they do.

This is a dirty little secret of the American justice system. Often, the cost of defending oneself is so burdensome that a guilty plea — if not disabling to one’s profession, such as law or medicine — offers a tolerable and far less expensive way out. In my years as a trial judge in New Jersey, I accepted more than 1,000 guilty pleas. I always asked if the defendant was truly guilty, and the defendants always replied affirmatively. But the guilt of those pleading guilty is often a legal fiction, practiced every day in courthouses around the United States.

Paul Manafort was convicted of financial crimes by a jury and also pleaded guilty to other financial crimes. Roger Stone was indicted for lying to Congress and is scheduled for trial in the fall. Jerome Corsi, who was interrogated extensively by Mr. Mueller’s FBI agents, was threatened with indictment, revealed the threat and was never indicted.

I recount this thumbnail history to remind readers that Mr. Mueller delved into many more areas than President Donald Trump’s behavior. Knowing federal prosecutors as I do, I am comfortable suggesting that more people were swept up into this investigation and were not charged with any crimes. Under the law, Mr. Barr and his team must be told of all this, but the public has no right to know who these folks are or what they discussed with the FBI.

Now back to Mr. Barr’s four-page assessment. The Department of Justice (DOJ) is in the business of investigating crimes and determining if it has sufficient, lawfully acquired evidence to prosecute and to prove guilt beyond a reasonable doubt. The DOJ is not in the business of exoneration. In fact, the word “exoneration” and the concept appear nowhere in the U.S. Code or the Federal Rules of Criminal Procedure. To offer, as Mr. Barr has in his letter, that Mr. Mueller exonerated Mr. Trump is to offer nonsense. Jay Sekulow, one of Mr. Trump’s personal lawyers, acknowledged as much publicly last weekend.

In his letter, Mr. Barr did not write that Mr. Mueller found no evidence of a conspiracy. Conspiracy is an agreement to commit a crime, whether or not that crime is actually committed. This is what the media and the president have been calling collusion. “Collusion” also does not appear in the U.S. Code and does not describe criminal behavior. It was insinuated into our vocabulary by Mr. Trump’s television lawyer, former New York City Mayor Rudy Giuliani, after a successful but deceptive word game campaign.

As well, Mr. Barr did not write that Mr. Mueller found no evidence of obstruction of justice. Obstruction is not a crime that requires completion, only a serious attempt. If I tackle you on your way into a courthouse where you plan to testify against me, so as to impede your testimony, then I have committed obstruction, even if you subsequently give the intended testimony.

The reason for my criticism of the no collusion and no obstruction bandwagon riders is because we know that Mr. Mueller must have found some evidence of conspiracy and some evidence of obstruction — just not enough to prove guilt beyond a reasonable doubt. Mr. Barr tipped his hand to this when he wrote in his letter that the DOJ could not “establish” these crimes. That’s lawyer-speak for “could not prove them beyond a reasonable doubt.”

If Mr. Mueller had found no evidence whatsoever of conspiracy and obstruction, Mr. Barr would have said so in his letter. He didn’t. So, will we see whatever evidence Mr. Mueller did find?

We also know that, according to some on the Mueller team, the flavor of whatever Mr. Mueller found did not come through in Mr. Barr’s four-page letter, and some have voiced privately to the media their displeasure. This has caused the president to accuse Mr. Mueller’s team of unlawful leaking. That is not necessarily so.

Voicing displeasure is one thing — “wait for the full report to come out and decide for yourself if the Attorney General fairly characterized it” — revealing 6(e) materials is another. The former is protected free speech. The latter could be career-ending.

Where does all this leave us? In the hands of Bill Barr. The House Judiciary Committee wants to see the evidence, which Mr. Barr will argue the law requires him to keep secret. Yet, did the president waive his privacy rights when he called for the public revelation of the full Mueller report? A federal judge will soon answer that question, as well as this one: With respect to the president, which is the higher value — privacy or truth?

• Andrew P. Napolitano, a former judge of the Superior Court of New Jersey, is a regular contributor to The Washington Times. He is the author of nine books on the U.S. Constitution.

Please read our comment policy before commenting.