OPINION:

On Aug. 14, 1862, in what may have been the first time a “black-majority” meeting was held at the White House, President Abraham Lincoln welcomed a committee of free black ministers to discuss a proposition he was considering. He informed them that Congress had appropriated money “for the purpose of aiding the colonization in some country of the people, or a portion of them, of African descent.” Lincoln wanted the black ministers to help him sell the plan. The Great Emancipator wanted Americans of color emancipated to another country. Surprisingly, this wasn’t the first time such an idea was put forward.

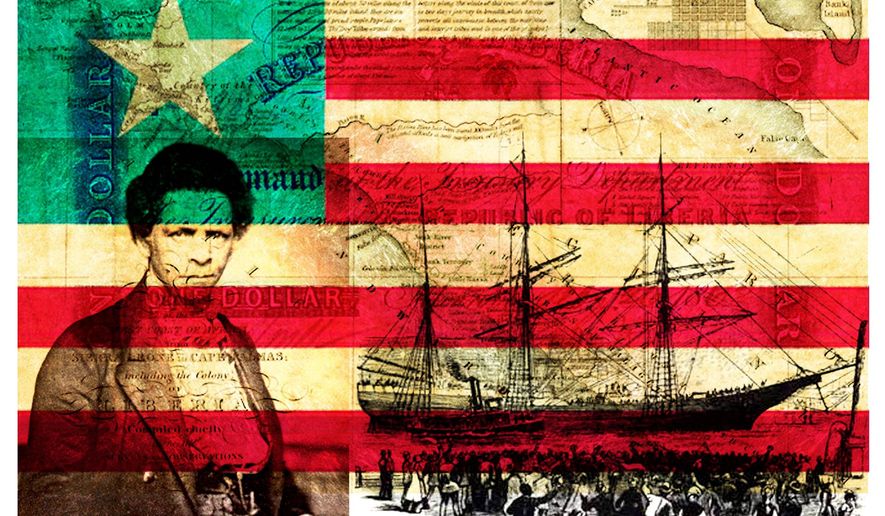

On the corner of Hamilton Street and Colorado Avenue in Washington, D.C., an embassy waves a familiar flag. At first glance you’d call it the “Red, White, and Blue” yet it’s short two stripes and about 49 stars. This is the Flag of Liberia. The Liberian flag takes obvious and direct inspiration from the United States. Its name, Latin in origin but American in conception, promised Americans of color something tragically denied to them: libertas, liberty, freedom.

Founded by the American Colonization Society, a group of men who believed that freed slaves had better chances closer to their roots, Liberia became a beacon for the freed slave. Presidents of the Colonization Society included James Madison and Henry Clay. “There is a moral fitness in the idea,” said the latter, “of returning Africa her children, whose ancestors have been torn from her by the ruthless hand of fraud and violence.”

The motivations for the members of the American Colonization Society varied widely. At best, they were abolitionists who genuinely believed the only way to correct the wrong of slavery was to return those forced into bondage to a country of their own. At worst, they were alarmists who feared that the freed slaves, if liberated, would slaughter their former slave masters and eradicate the agrarian way of life.

On either side, there seemed to be the view that former oppressors and the oppressed would never live in peace. Few took greater exception to this than freed slave Frederick Douglass. On Jan. 26, 1849, on the front page of The North Star, an anti-slavery publication, he wrote:

“For two hundred and twenty-eight years has the colored man toiled over the soil of America, under a burning sun and a driver’s lash — plowing, planting, reaping, that white men might roll in ease, their hands unhardened by labor, and their brows unmoistened by the waters of genial toil; and now that the moral sense of mankind is beginning to revolt at this system of foul treachery and cruel wrong, and is demanding its overthrow, the mean and cowardly oppressor is meditating plans to expel the colored man entirely from the country. Shame upon the guilty wretches that dare propose, and all that countenance such a proposition. We live here — have lived here — have a right to live here, and mean to live here.”

Despite these protests, the colony of Liberia was founded and, if Lincoln had his way, there would be more “Liberias” to come.

Abraham Lincoln was a big supporter of the “colonization” of former slaves. During the Lincoln-Douglas debates in 1858 he said, “If all earthly power were given me, I should not know what to do as to the existing institution. My first impulse would be to free all the slaves and send them to Liberia — to their own native land. But a moment’s reflection would convince me that, whatever of high hope there may be in this, in the long run, its sudden execution is impossible.”

It was a matter of practicality, not ideology. “The enterprise is a difficult one,” he had said in a speech in Springfield, Illinois, a year earlier, talking of interracial marriage, “but ’when there is a will there is a way;’ and what colonization needs most is a hearty will.”

Two years later, and the issue of slavery, no matter how much President James Buchanan tried, was not going away. The Civil War was fought singularly on whether the states had the right to enslave other human beings. Yet Lincoln still had that idea of “colonizing” freed men, and on April 16, 1862, Lincoln signed the District of Columbia Compensation Act, which emancipated all slaves in the District, and slaveholders, in compensation, would receive $300 per slave. Additionally, $100 were given to each slave should he or she choose to leave the United States.

The issue came to a head on Jan. 1, 1863, with the Emancipation Proclamation, in which all slaves in the Confederate-controlled states and territories were to be freed. What next? According to earlier drafts of the famous document, colonization. To that group of black ministers he met with in August, he said; “better for us both, therefore, to be separated.” The plans drew so little support that Lincoln quietly put them in a drawer. Without a doubt, Lincoln was well-intentioned. He earnestly wanted what was best for all, but perhaps he should have heeded the words of Frederick Douglass:

“We live here — have lived here — have a right to live here, and mean to live here.”

• Craig Shirley, a presidential historian, is the author of four books on Ronald Reagan. Andrew Shirley is the director of operations for Citizens for the Republic.

Please read our comment policy before commenting.