OPINION:

Faced with a 5-4 conservative majority on the U.S. Supreme Court, some liberal Democrats want to pack the court to reverse the balance. Once the Democrats regain control of the White House and the Senate, so the argument goes, the new Democratic president could create enough new seats on the Supreme Court to ensure a liberal majority.

The last time the Democrats tried that was in 1937. President Franklin Roosevelt had just been re-elected by the largest majority in American history. He carried all but two states, Maine and Vermont, and racked up unprecedented Democratic majorities in the Senate and House.

Not since Reconstruction had the nation been so close to one-party rule. The moment had finally arrived for FDR to square off against the Supreme Court — specifically, against the aging conservatives who had thwarted him by declaring huge chunks of the New Deal unconstitutional.

So FDR proposed to appoint one new justice for every sitting justice over the age of 70. That would allow him to add six new justices to the Supreme Court, raising the number from nine to 15. Such a court, he reckoned, would uphold the New Deal.

Yet despite the fact that he was now at the flood tide of his popularity and power, FDR failed at court packing. He failed for essentially three reasons: First, many Americans — even members of his own party — were alarmed at the power that his proposal would put into the president’s hands.

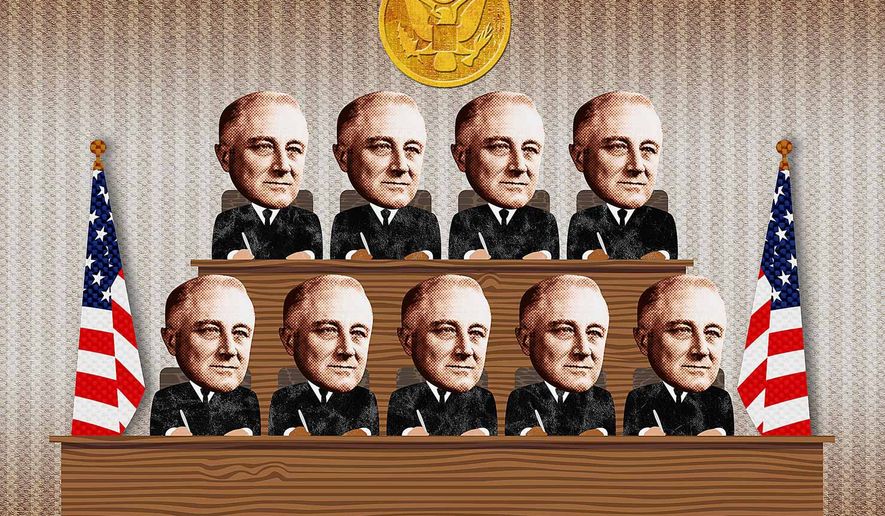

One political cartoon of the period depicted what the Supreme Court would look like if Roosevelt got his way. The cartoon showed the court’s nine sitting justices in the front row, and directly behind them were the six new justices — every one of whom was a clone of FDR. People got the point.

Second, it dawned on the New Dealers that they had overreached themselves. When, for example, the Supreme Court struck down the National Industrial Recovery Act in 1935, a crucial piece of New Deal legislation, the court was unanimous that the act’s delegation of legislative power to the Executive Branch was overbroad and therefore unconstitutional. Even liberal justices like Benjamin Cardozo and Louis Brandeis voted with the conservatives on that one, much to FDR’s chagrin.

Third, the tenor of the court changed. In 1937, Justice Willis Van Devanter, a leading conservative, resigned and was replaced by New Dealer Hugo Black. At about the same time, two swing votes, Chief Justice Charles Evans Hughes and Associate Justice Owen Roberts, made their peace with the New Deal and began finding it constitutional.

Their exact reasons for doing so are unknown, but it is likely that both feared for the independence of the Supreme Court if it continued to rule against the wishes not only of President Roosevelt but of the great majority of the American people. So the New Deal sailed triumphantly on and no more was heard about packing the court.

Will today’s court-packing schemes likewise peter out? Probably, if the liberals’ dire warnings of what an ideologically driven conservative court will do fail to materialize.

The conservatives sitting on today’s court are not firebrands. In her speech explaining her vote to confirm Justice Brett Kavanaugh, Sen. Susan Collins of Maine noted that when Justice Kavanaugh and Judge Merrick Garland were colleagues on the federal appeals court of the District of Columbia they voted the same way in 93 percent of the cases they heard together.

This degree of harmony is not unusual. In remarks delivered in Houston at Rice University a few years ago, Chief Justice John Roberts took pains to downplay ideology as a factor in the Supreme Court’s decisions. He said that the great majority of the cases that come before the court do not involve highly controversial issues, and therefore cannot be characterized as liberal or conservative.

He added that there is a higher degree of unanimity in the court’s decisions than the public realizes; fully two-thirds are reached with majorities of 6-3 or higher. And from what we know of Chief Justice Roberts, it is likely that he will do all he can to steer the court away from dangerous extremes and toward consensus.

Finally, there is the power of public opinion to check even the Supreme Court. As Mr. Dooley, Finley Peter Dunne’s fictional Irish bartender famously observed over a century ago, “Th’ Supreme Coort follows th’ election returns.”

And it does. We saw that in the fight over the New Deal, and we would likely see it again should the court’s conservatives attempt to overrule Roe v. Wade, Obergefell or Justice Roberts’ own opinion upholding Obamacare. In short, the more that cooler heads prevail, the worse the odds for court packing.

• Thomas C. Stewart is a former Naval Aviation attack commander and a retired New York investment banker.

Please read our comment policy before commenting.