OPINION:

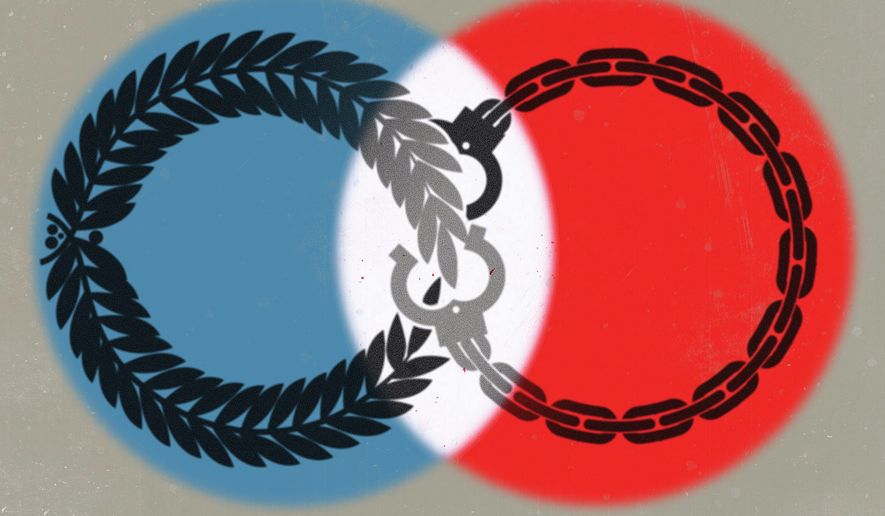

Would you prefer to live in a country that has a high degree of individual liberty but is not a democracy, or live in a democracy where individual liberties are curtailed?

A major reason for the Brexit move by the U.K. was the feeling among many British that they had lost much of their democracy and liberty to European Union (EU) bureaucrats. In the United States, many are demanding more voter enfranchisement, mainly because of the Electoral College, which is not based on an equal weighting per person among the states.

Before the British handed over Hong Kong to the Chinese in 1997 (albeit with a 50-year treaty specifying two political systems — one for Hong Kong and one for China), the residents of Hong Kong enjoyed much individual freedom and basic civil liberties, strong protections for private property, the rule of law and a competent and honest civil service. What they did not have was democracy because they were British subjects ruled (ever so lightly) from London. Under British management, Hong Kong went from a poor place to a rich one — and few objected to the governing system (which was in effect a very benign dictatorship).

In recent years, the Chinese have reneged on some of their promises in the transfer treaty and have interfered with some of the basic liberties enjoyed by those who live in Hong Kong. This is fueling demands by residents of Hong Kong for democracy. In the absence of a benevolent king, democracy with all its imperfections seems to be the best that mankind can come up with. Or as Winston Churchill put it: “Indeed it has been said that democracy is the worst form of Government except for all those other forms that have been tried from time to time.”

Governments are created to protect person and property, and to ensure liberty. Democracy is a partial means to that end, not the end in itself. Simple majoritarian democracies have a record of running over rights of minorities, including economic minorities. From the time of the ancient Greek city-states, democracies have been established from time to time, but have never lasted. Those longer-lived modern democracies have all restricted the voter franchise in one way or another until recent years. In the United States, originally, the voting franchise was limited to male property owners. Finland was the first country to give women the right to vote back in 1906, and those very democratic Swiss did not give the women the right to vote until 1971.

Under unrestrained democracy, majorities can tax or regulate minorities almost out of existence, or vote for people who destroy the democracy — as did the Germans in voting for Hitler, and the Venezuelans in voting for Hugo Chavez and Nicolas Maduro. The American Founding Fathers were well aware of the failures of previous attempts to create democracies, which is why they established the United States as a constitutional federal republic rather than a direct democracy.

A constitution that limits the powers of the state, contains checks and balances, and can only be amended by super-majorities is fundamentally an undemocratic document. The Founders’ contemporary, Scottish historian Alexander Tytler, noted: “A democracy will continue to exist up until the time that voters discover that they can vote themselves generous gifts from the public treasury.”

Political jurisdictions most often lose their democratic independence because of the unsustainable spending and debt. Countries such as Argentina and Greece have given up part of their fiscal sovereignty to the IMF and to both foreign government and private creditors. In the United States, judges have taken power away from elected officials when local governments have gone bankrupt. Some states, such as Illinois, New Jersey and Connecticut, are facing a fiscal crises largely because of too generous and underfunded government employee pensions, so it probably is only a matter of time before judges, rather than elected officials, are running these states.

Successful democracies require informed and engaged electorates who have a reasonable grasp of the issues and access to their representatives. The United States and the EU have grown so large that most citizens no longer have access to the politicians at the national level who rule much of their lives — hence, the growing discontent with their governments.

Democracies seem to work best in smaller political entities like the Scandinavian countries and Switzerland, where access and influence is still possible by ordinary citizens. The U.S. and other large democracies should engage in a massive devolution of power to the smaller units of governments (i.e. states and towns) to regain legitimacy in the minds of many voters.

Many Swiss are sufficiently alarmed about the loss of their sovereignty that they voted on a referendum this past Sunday that would have required Swiss law to take precedence over international law and treaties. The proposal went down to defeat because many thought it was too far-reaching, but even so, about a third of the Swiss population voted for it. (Note: the Swiss Constitution, passed in 1848 and somewhat modeled after the U.S. Constitution, requires referendums on all major questions — with the requirement that not only a majority of the people vote for the proposal but also that a majority of the cantons {states} also vote “yes” — which provides an additional bulwark against irresponsibility).

Both too much and too little democracy contain the seeds of its own destruction. Finding the proper balance is an enduring task.

• Richard W. Rahn is chairman of the Institute for Global Economic Growth and Improbable Success Productions

Please read our comment policy before commenting.