OPINION:

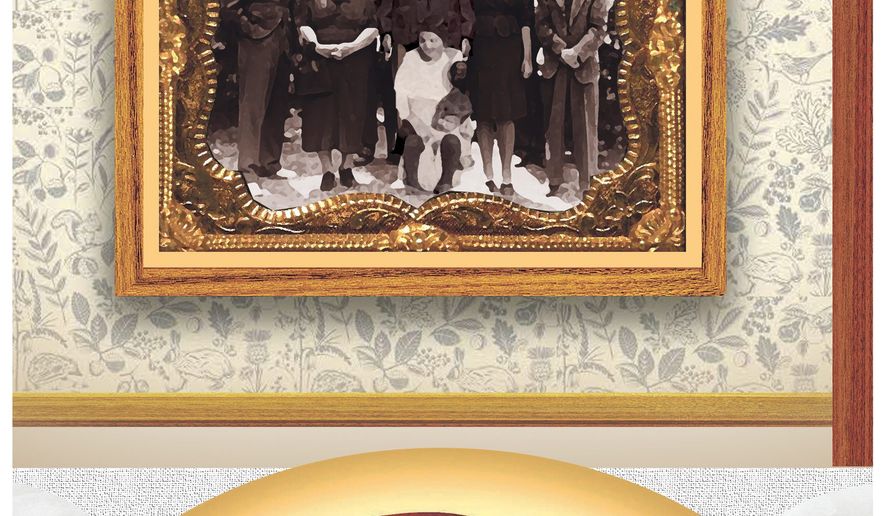

Years ago I framed an old family photograph and put it in a prominent place for Thanksgiving visitors to see. Four of us are elegantly posed by the photographer, taking ourselves oh-so-seriously for the family album.

The younger generations gathered around the table to see their parents and grandparents at a younger stage of their lives which their progeny could scarcely imagine. The portrait, in black and white no less, was made for posterity, not just on a fleeting Instagram. Daddy and my brother were solemn in their best dark suits, with a white handkerchief in their breast pockets, and my mother and I were showing off a notion of what we hoped was stylish sophistication. Like mother, like daughter.

Such a photograph, and many more like it, predated second-stage feminism, with a handsome patriarch and breadwinner at the head of the family, and a beautiful woman as second-in-command. Today this traditional family portrait is caught in a cultural time warp. It was the back story of the jest that the matriarch made the little decisions in the family, such as where they went on vacation and what they had for dinner, and the patriarch made the important decisions, such as “whether we should recognize Red China.”

Daddy was the breadwinner, pleased that my mother didn’t have to work outside the home, which she never did after they tied the marital knot. She was pleased that in the family order she “ruled the roost.” Betty Friedan, in her groundbreaking book “The Feminine Mystique,” called this arrangement “a comfortable concentration camp,” a nasty phrase to make a feminist point by cruelly condescending, an insult without insight.

None of the children or grandchildren in the family would have traded the matriarch in the portrait for a brain surgeon, a Wall Street titan or Supreme Court justice, as impressive as those professions and trades may be. Many contemporary women who can’t imagine a man eager to take complete responsibility for supporting a family might find a patriarch like my daddy refreshing, with many women overwhelmed with double burdens and responsibilities.

Such a family portrait can stimulate lively and spirited conversation bordering on angry debate between modern generations, when identity politics dominates everything as young men and women and men debate changing interpretations of relationships, and none more so than the intimate ones between men and women. That’s as it should be, offering food for thought from a contemporary point of view, giving new meaning this Thanksgiving season to “talking turkey.”

There’s the usual worry whether everyone will maintain civility and respect for different opinions, or whether the bubbles we live in will collapse and the idea of amiable exchange (and family relationships) will collapse with them. In the age of Trump, when outrage and hostility flood social media and cable television, and those with differing points increasingly look at “the other” as ignorant, insensitive and even evil, we worry whether the mystic bonds of family can hold for another year. Can we rise above the identity politics that canonizes self-righteous opinion?

Two years into the Trump era, cultural and political divisions make the holiday treacherous treading. New generations of rebels have always been ready to spar with the traditionalists. Most families can find divisions rising from early immigrant stories of Mayflower descendants of thin blood, waves of robust Europeans escaping grinding misery and now Asians, Hispanics, African and Middle Eastern refugees looking for better lives. African-Americans, whose history began in slavery, have their own unique stories and many now are entering the middle class.

What’s troubling is that the debate does not inspire unity and assimilation as it once did, but elevates differences and division. Bonds of family and nation are weakened by ideological strife. When I bought a bag of organic apples at my neighborhood farmers’ market this week, I remarked that I treasured the Thanksgiving holiday because it brought family together in a special way, the young woman selling apples went out of her way to undercut joy with a tirade about how “horrid we were to the Native Americans.”

Sometimes we were. But history is complicated, and there’s even a movement now to teach everyone to “unlearn” the Thanksgiving stories we once learned together, and in the rush to baste the turkey we forget that the spirit of the holiday reflected in the words of the Dutch hymn, “We gather together to ask the Lord’s blessing/He chastens and hastens His will to make known.” Thanksgiving is about a shared feast but it’s first about gratitude. We forget that at our peril. The pilgrims and their native hosts at Plymouth offered each other not merely a feast but a generosity of spirit that enabled survival through excruciatingly hard times. May we enjoy the season once more in that spirit.

• Suzanne Fields is a columnist for The Washington Times and is nationally syndicated.

Please read our comment policy before commenting.