OPINION:

If one reads the headlines associated with the results of a congressionally mandated review of the new National Defense Strategy by a bipartisan study commission, one would conclude that the nation’s generals and admirals are quietly engineering a coup against the concept of civilian control of the military establishment. An actual reading of the report, titled “For the Common Defense,” is much less alarming.

At the present time, the secretary of Defense — who happens to be a retired Marine Corps general — appears to rely more on professional military advice than he does on his own civilian staff (the Office of the Secretary of Defense) for advice. This is probably true, but it is hardly the threat to democracy that the headlines imply. Anyone who thinks that the current president is not firmly in charge of the nation’s war-making capabilities hasn’t been following the news.

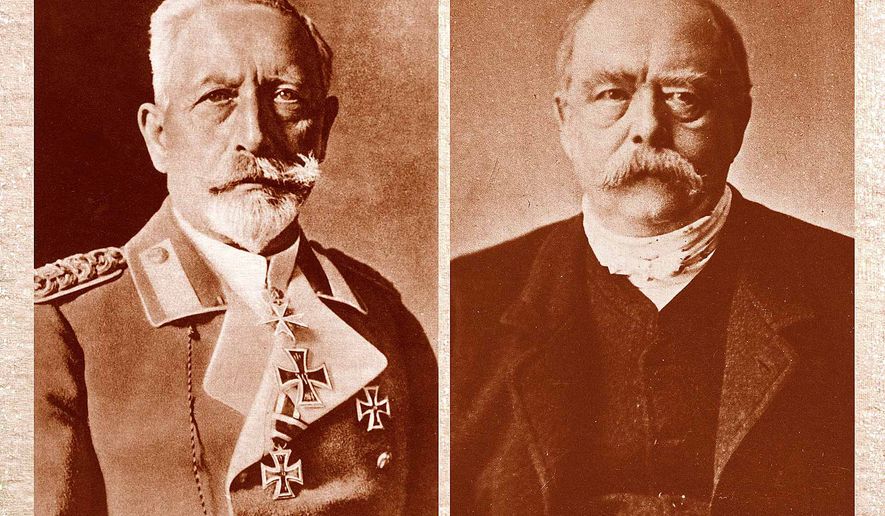

The real danger to any nation’s national security comes when the civil-military relationship gets permanently out of balance. The most disastrous example of this is Germany from 1890 to 1945. Under Otto von Bismarck — the Iron Chancellor — civilian leadership in Prussia (later Imperial Germany) was unquestioned. The leader of the Prussian armed forces was Gen. Helmuth von Moltke. Although a military genius, Moltke never seriously questioned the civilian leadership of the king or Bismarck, even when he disagreed. Together, they achieved Bismarck’s vision of a unified Germany under Prussian leadership.

The trouble started when Kaiser Wilhelm II ascended the throne. Wilhelm was jealous of Bismarck’s reputation and became impatient for a war with somebody in order to make a name for himself. Wilhelm sacked Bismarck in 1890. Although retaining supreme power, the kaiser left the details of national strategy in the hands of the military general staff. The military had what it thought was a good war plan, but lacked the diplomatic foresight to realize that it would mean a general European war. The result was the disastrous defeat of World War I and the abdication of the kaiser. Absent competent civilian strategic input, Germany doomed itself to failure.

In the run-up to World War II, the situation reversed itself with equally disastrous results. Hitler, a civilian, believed himself to be a strategic genius and his early international triumphs only reinforced that notion. He rapidly became dismissive of his generals and began using them as lackeys. The balance had shifted to unbalanced civilian absolute control. Again, the end result was a debacle.

America has not been immune from this civilian-military imbalance. Presidents Kennedy and Johnson have both been criticized for over-reliance on Robert McNamara’s civilian analytical leadership during the disastrous Vietnam War. All of the three served in the military during World War II, but none of them could be called military men. George W. Bush has similarly been accused of over-reliance on civilian neo-conservative advice early in the Iraq War before bringing in a balanced civilian-military team of advisers in Robert Gates as Defense secretary and Gen. David Petraeus as the commander in Iraq.

The myth of military men as being knuckle-dragging war lovers is popular among some progressives, but the reality shows contrary evidence. We have had four former general officers as president and two as secretary of Defense. To date, none have gotten us into a war. Three (George Marshall, Dwight Eisenhower and James Mattis) have been charged with getting us out of wars that they inherited. The public has roundly rejected two hawkish former general officers as nominees for national office — Douglas MacArthur as president and Curtis LeMay as vice president.

It is likely that Defense Secretary Mattis and President Trump are currently favoring military advice, and there are two reasons for this. The hiring freeze of 2011 has largely stunted the growth of a young generation of civilian national security professionals, and many of the old guard have left the Pentagon or are distrusted by the president as being potential “never-Trumpers.” Absent a perceived lack of competent civilian advice, it is no surprise that Mr. Mattis has turned to military professionals whom he has worked with. All senior officers are war college graduates trained in strategy and force analysis. All have master’s degrees and some have doctorate degrees.

The mix of civilian-military advice is essentially personality preference of the guy at the top and transitory. If Mr. Mattis leaves, and the president desires to appoint a hawkish civilian as secretary of Defense, the balance could change radically. If that happens, no recommendation by any blue-ribbon study panel will change that.

• Gary Anderson is a retired Marine Corps Colonel who lectures on Alternative Analysis at the George Washington University’s Elliott School of International Affairs.

Please read our comment policy before commenting.