BEIJING (AP) — A Chinese university’s plan to conduct a blanket search of student and staff electronic devices has come under fire, illustrating the limits of the population’s tolerance for surveillance and raising the prospect that tactics used on Muslim minorities may be creeping into the rest of the country.

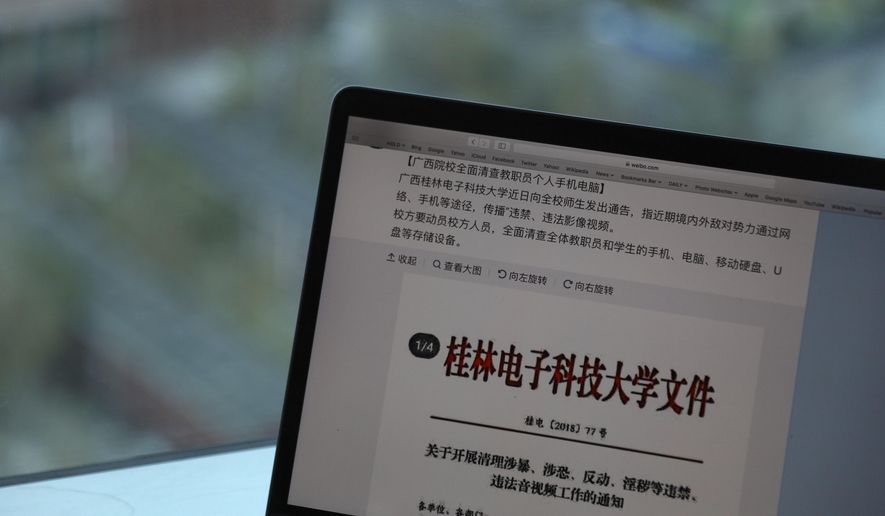

The Guilin University of Electronic Technology is reconsidering a search of cellphones, computers, external hard disks and USB drives after a copy of the order leaked online and triggered such an intense backlash that it drew rare criticism in state-run newspapers.

Searches of electronics are common in Xinjiang in China’s far west, a heavily Muslim region that has been turned into a virtual police state to tamp down unrest. They are unheard of in most other areas, including where the school is located in the southern Guangxi region, a popular tourist destination known for spectacular scenery, not violence or terrorism.

That’s why the planned checks worry some.

“Xinjiang has emerged as China’s surveillance laboratory,” said James Leibold, a scholar of Chinese ethnic politics and national identity at La Trobe University in Australia. “It is unsurprising that some of the methods first pioneered in China’s west are now being rolled out in other regions.”

Under President Xi Jinping, the government has in recent years tried to tighten controls over what the public sees and says online and stepped up political oversight of universities. Sometimes, these measures have run into a new generation of Chinese accustomed to greater freedoms, sparking public outcry and occasionally government retreat.

The leaked notice in Guilin warned that hostile domestic groups and foreign powers are “wantonly spreading illicit and illegal videos” through the internet. It said the search for violent, terrorist, reactionary and obscene content, which was to be conducted this month, was necessary to resist and combat extremist recordings that it called mentally harmful.

The order triggered a public uproar last week.

Posts on China’s Twitter-like Weibo site with hashtags on schools checking electronic devices were viewed nearly 80 million times. Users voiced privacy concerns, comparing the measure to computer chips inserted in brains and the George Orwell novel “1984.”

Then came critical editorials in state-run publications saying the notice could violate Chinese constitutional protection of the right to communicate freely and have those communications remain confidential.

“If colleges and universities check the phones, computers, and hard disks of teachers and students, they’re suspected of infringing on communication freedom and privacy,” said an editorial in the Beijing Youth Daily. “Those responsible at the school should be held accountable, as they had a great negative impact on the school’s image.”

Administrators told another state-owned publication, “The Paper,” that the search had not yet been carried out, and that they were considering reducing its scope. University and local education ministry officials referred questions to a media office, which did not answer repeated phone calls.

Weibo, while not a government body, ran into hot water in April when it said it would censor content related to gay issues on its microblog. The company backpedaled under intense criticism, including from state-run publications.

It’s unclear what prompted the Guilin university’s planned search. It could have been a trial run to see how the public would react or an overzealous local administrator, said Christopher Colley, a National Defense College of the United Arab Emirates assistant professor who has lectured at Chinese universities.

Either way, he said, the backlash shows that though online censorship is common in China, physical searches of phones and laptops is an extreme measure that many will not accept.

“Most people in China are willing to tolerate Big Brother as long as it contributes to social stability, but for many, this is going too far,” Colley said.

Schools in Xinjiang have been conducting similar searches since the region’s highest court in early 2014 issued a notice forbidding audio and video recordings promoting terrorism, religious extremism and ethnic division.

Teachers and administrators at Xinjiang Normal University’s College of Physics and Electronics searched electronic devices in every dormitory on campus on Nov. 9, 2014. A post about the search on the school’s website says, “Through investigating violent and terroristic videos, religious extremism on campus has been weakened.”

In 2017, China University of Petroleum’s branch in Karamay, a city in oil country in Xinjiang’s north, ordered various school departments to assign inspectors to search the computers of all teachers on campus.

Xinjiang is home to a large Uighur population, a Muslim ethnic group that has long harbored simmering resentment against rule from Beijing. A series of riots and attacks blamed on separatist Uighurs has prompted a sweeping crackdown on Muslims in the region.

China has rolled out one of the world’s most aggressive surveillance and policing programs both in Xinjiang and neighboring Tibet.

Uighurs are regularly singled out and stopped at checkpoints to have their smartphones scanned for religious content. As The Associated Press reported in May, they risk being detained and sent to internment camps if police find songs or videos they deem suspicious or apps that are commonly used to contact people outside China, such as WhatsApp.

“Xinjiang today appears to be the leading-edge of a highly intrusive and coercive surveillance society that the (Communist Party) is intent on constructing across China,” Leibold said.

Please read our comment policy before commenting.