ATLANTA (AP) - When Barbara Williams arrived at the Pittman Park Recreation Center just before noon on Election Day to cast her vote, she saw a line so long that the end wasn’t in sight.

“There were so many people, you couldn’t count them,” Williams recalled. “They were looped around. The line started at the door and it snaked around to the left.”

She ultimately waited four hours to use one of the three voting machines at the precinct where the 58-year-old retiree has voted in every election since she turned 18. Others reported similar challenges to voting at Pittman Park, located in the heart of Atlanta’s oldest black neighborhood: Hours-long waits and voters leaving in frustration. For Williams and others who sought to vote at Pittman Park, the hurdles echoed a long history of voter suppression unfolding in a race in which Democrat Stacey Abrams is seeking to become the nation’s first black female governor.

“I feel like they didn’t want her to win,” Williams said of Abrams. “They made things so that we would get aggravated and people would leave.”

The race between Abrams and her Republican opponent, Brian Kemp, is still too close to call five days after the election. Kemp has denied any attempt to suppress the vote. But his background as someone who, as secretary of state, deleted inactive voters from registration rolls and enforced an “exact match” policy that could have prevented thousands from registering to vote, has brought the issue of minority access to the polls to the forefront.

That’s especially true at Pittman Park, which has long been a center of black civic and community life. Many residents learned to swim there at the only pool they were allowed to use during the segregation era. Today, it offers after school care, classes for seniors and a space for local meetings.

It has been a precinct for as long as Douglas Dean, head of the Pittsburgh Neighborhood Association, can remember. Three years ago, it was consolidated with a nearby polling station, doubling the number of registered voters to nearly 3,800, according to the Fulton County Board of Elections, one of the factors that may have played into last week’s lines.

“There is no excuse for what happened here in this election,” said Dean, 71, and a former state representative. “Georgia is changing and there are some whites who want everything to stay the same so that they remain in power. We’ve been fighting this battle for years. This is nothing new.”

The Rev. Jesse Jackson, who had been troubleshooting election irregularities in the city that day, was at the precinct Tuesday to investigate.

“They were four deep in the room,” Jackson said, describing the scene in an interview. “Some were in wheelchairs, some were on walkers, some were sick. I appealed to them to stay. Either incompetence or corruption or both is what happened.”

Williams fought back, maintaining her place in line and pleading with others to do the same.

“It was important for me to vote,” she explained. “I vote in every election. I’m a human being and I have a life and I try for it to be better. A whole lot of people left. I even tried to get some of them to stay. I said, ’That’s what they want you to do.’”

Joseph Jarrett came at around the same time as Williams, with his 4-year-old son in tow to show him the significance of voting. When he saw the line, Jarrett left, not wanting to stand there with a restless toddler.

He debated whether or not to come back. On his mind were lessons from childhood. He thought of the Mississippi voting activist Fannie Lou Hamer, a personal hero, and what she did for the community. Jarrett retuned to the line just after 2 p.m. Three hours later, he cast his ballot.

“I was determined to vote,” said Jarrett, 38. “Our whole community was galvanized by Stacey Abrams’ campaign. But some people came in, saw the line, and walked right back out.”

Others also tried to persuade people to be patient, attempting to counter frustration with a festive atmosphere. A band arrived and played music. Dozens of pizzas and refreshments appeared. When the rain broke, the sizzle of a grill began in the parking lot.

Jackson took selfies to try to lift spirits. He also went to a playbook that has worked for him since the civil rights movement: He mobilized the press and created a scene. Soon, five brand new machines, still in the wrapper, were brought to the concrete building on Garibaldi Street. But by then, some of the damage had already been done.

“Some people had to leave and go to work,” Jackson said. “Some had to go home and get their medicine. Some people became discouraged. Denial of opportunity, denial of access to democracy … That’s what voter suppression looks like. I’ve seen this for a long time.”

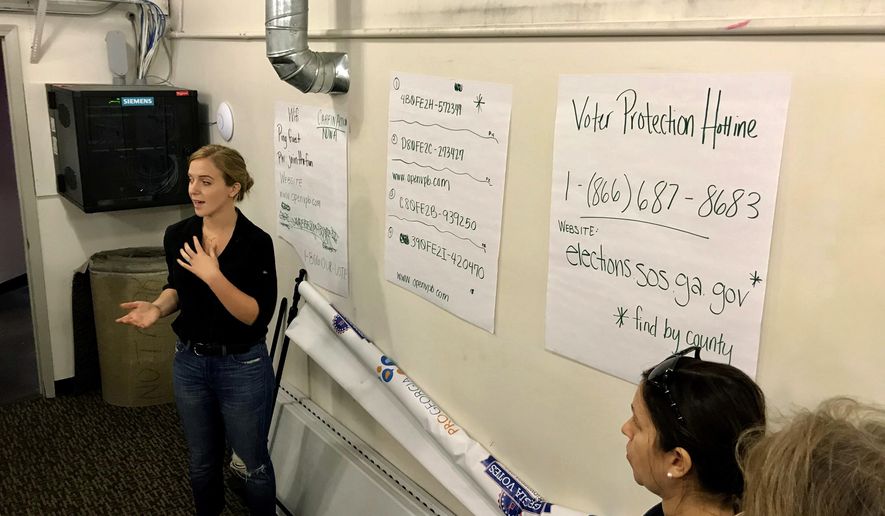

Voters in other black neighborhoods complained of long lines and inadequate resources, too. As the hour drew near for the polls to close, the Georgia NAACP won its lawsuit to extend voting hours for three precincts in Fulton County, including Pittman Park. When the lights were turned off after the last ballot was cast, it was 1 a.m., according to workers at the center.

Nearly a week after the election, even those who were able to vote are left wondering whether they were excluded from the process, despite their perseverance. The fight continues, as Abrams has sued a southwest Georgia county over absentee ballots and has vowed to stay in the race until the recount is complete.

“I think she probably did win, but I don’t think she’ll be the governor, because I don’t think they’ll do the right thing,” Jarrett said of Abrams. “It’s a damn shame, because people really came out. For their votes not to be counted … it’s like a disgrace to democracy.”

___

Whack is The Associated Press’ national writer on race and ethnicity. Follow her work on Twitter at http://www.twitter.com/emarvelous .

Please read our comment policy before commenting.