OPINION:

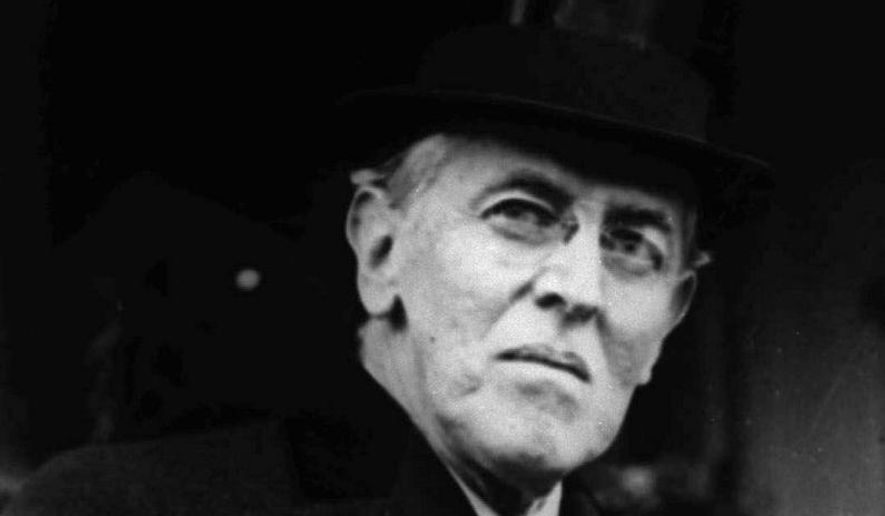

The headline above is deliberately provocative. At a time when there is a real focus on the rising power of the administrative state, it’s worth recalling President Woodrow Wilson’s argument that our traditional understanding of the U.S. Constitution should give way to what he considered the new realities of modern government.

Wilson is perhaps best known for expressing his intent in his April 1917 war message to make the world “safe for democracy.” Much less known is the key role Wilson earlier played — as a professor of political science and president of Princeton University — in the Progressive Era to “make the United States safe for the modern administrative state.”

As far as I know, Wilson never stated his intent to remake the American system of government in exactly those terms. But he exhibited remarkably little reticence regarding his objective — and the need, in his view, to alter the then-prevailing understanding of the Constitution’s dictates.

While Wilson’s political theories and the role they played in the rise of early 20th century Progressivism have been the subject of many scholarly works, Jonah Goldberg’s retelling in his new book, “The Suicide of the West,” discusses Wilson’s writings, and I borrow from his discussion here. Wilson was convinced, in no small measure by his admiration for prominent late 19th century German social scientists, that “modern government” should be guided by administrative agency “experts” with specialized knowledge beyond the ken of ordinary Americans — and that these experts shouldn’t be unduly constrained by ordinary notions of democratic rule or constitutional constraints.

So, in his seminal 1887 article, “The Study of Administration,” published in the same year that the first modern regulatory commission, the Interstate Commerce Commission, was created, Wilson explained that he wanted to counter “the error of trying to do too much by vote.” Hence, he admonished that “self-government does not consist in having a hand in everything,” while pleading for “administrative elasticity and discretion” free from checks and balances.

Not surprisingly, Wilson’s conception of government run by administrative “experts,” unconstrained by popular consent, runs up against the traditional understanding of the Founder’s Constitution, with its tripartite system based on a separation of powers among the legislative, executive and judicial branches. Modern administrative agencies exercise a combination of legislative, executive and judicial powers without a clear separation of functions. Thus, the same agency commissioners make binding law through the exercise of rulemaking power, issue guidance regarding enforcement of the rules, and adjudicate alleged violations of the rules.

Wilson well understood that his notion of Progressive governance by “fourth branch” administrative experts was constitutionally problematic. In 1891, he wrote that “the functions of government are in a very real sense independent of legislation, and even constitutions.” Regarding this view that the Constitution was an obstacle to be overcome, not a legitimate charter establishing a system of checks on government power, Wilson never wavered. He complained in 1913 as president: “The Constitution was founded on the law of gravitation. The government was to exist and move by virtue of the efficacy of ’checks and balances.’ The trouble with the theory is that government is not a machine, but a living thing . No living thing can have its organs offset against each other, as checks, and live.”

As the Progressive Era, and then the New Deal, unfolded with an expanding array of “alphabet” agencies — the FTC, FCC, SEC, NLRB and so forth — under a newly-conceived “living Constitution,” Wilson’s acolytes continued to argue that traditional understandings of the Constitution must not be allowed to restrict broad agency power. Supreme Court Justice Felix Frankfurter, upholding an indeterminate congressional delegation of authority to the FCC to act in the “public interest,” warned: “There shall be no withdrawal from these experiments.”

And James Landis, a leading proponent of the New Deal “expert” agencies, as chairman of the SEC and then dean of Harvard Law School, put it just as bluntly in 1938. He declared that agencies be granted “all necessary powers” and urged that we ought “not [be] too greatly concerned with the extent to which such action does violence to the traditional tripartite theory of government organization.”

Fast-forward 75 years. It should not be surprising to find Chief Justice John Roberts, albeit in a 2013 dissent from a decision according so-called Chevron deference to an agency’s determination of its own jurisdictional limits, expressing concern “that the administrative agencies, as a practical matter, draw upon a potent brew of executive, legislative, and judicial power.” This concern, according to Justice Roberts, is heightened “by the dramatic shift in power over the last 50 years from Congress to the Executive — a shift effected through the administrative agencies.”

Have Woodrow Wilson and the Progressive Era theorists so thoroughly prevailed that surrender is the only option? While that’s largely a subject for another day, it’s true that, for the most part, the administrative agencies are here to stay. Indeed, some perform worthwhile functions, particularly in the health and safety areas.

But this does not mean the agencies should not be subject to proper constraints consistent with our constitutional design. For starters, this means limiting the broad discretion agencies exercise by restricting the deference their decisions currently are accorded under judge-made doctrines such as Chevron. And Congress should do its part in curbing administrative power by narrowing the scope of its delegations of agency authority.

The reason to undertake these measures is not to serve as a rebuke to long-gone Woodrow Wilson. It is to ensure we are not ruled by a government of “expert” administrators, but rather one constrained by the Constitution’s embodiment of separation of powers and popular consent.

• Randolph May is president of the Free State Foundation.

Please read our comment policy before commenting.