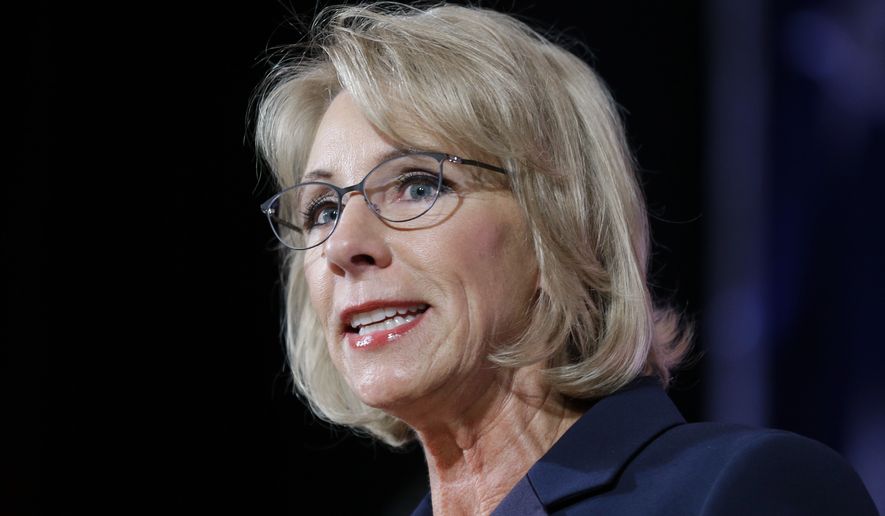

Education Secretary Betsy DeVos is coming under renewed pressure to uproot the Obama administration’s lenient school-discipline directive, which critics say backfired tragically with last month’s high school shooting in Parkland, Florida.

Sen. Marco Rubio, Florida Republican, has urged Mrs. DeVos to overhaul the 2014 “Dear Colleague” letter on school discipline, a joint guidance by the Education and Justice departments that threatened schools with federal civil rights probes unless they reduce law-enforcement referrals, suspensions and expulsions of minority students.

Those policies, embraced at the outset by the Broward County Public Schools, have been blamed for allowing shooting suspect Nikolas Cruz to avoid being arrested or taken into custody despite committing offenses such as assault and carrying bullets to Marjory Stoneman Douglas High School.

“The overarching goals of the 2014 directive to mitigate the school-to-prison pipeline, reduce suspensions and expulsions, and to prevent racially biased discipline are laudable and should be explored,” Mr. Rubio said Monday in a letter to the education secretary. “However, any policy seeking to achieve these goals requires basic common sense and an understanding that failure to report troubled students, like Cruz, to law enforcement can have dangerous repercussions.”

Mr. Rubio said the guidance should be revised “to ensure that schools appropriately report violence and dangerous actions to local law enforcement,” while others have encouraged Mrs. DeVos to repeal it outright.

“In the tragic aftermath of the murders in Florida, which were preventable, we simply cannot take the chance that other school districts, in response to a Dear Colleague letter issued in 2014 by the Obama administration, will continue to enforce or will implement the disastrous race-based, discipline-free program put in place in December of 2013 by Broward County,” William Perry Pendley, president of the Mountain States Legal Foundation, said Friday in a letter to Mrs. DeVos.

“The risk to human life and safety is far too great,” Mr. Pendley said.

Adopted by more than 50 large school districts, policies aimed at using counseling to address nonviolent offenses have been cheered for improving student retention rates — Broward County saw school-based arrests plummet by 63 percent from 2012 to 2016 — and have been criticized for making schools more dangerous and disruptive by turning them into punishment-free zones.

One problem with revising rather than rescinding the directive is that it would still be in place for another administration to resurrect, said Manhattan Institute senior fellow Max Eden.

“It ought to be rescinded, then temporarily replaced while the administration opens official negotiated rule-making to put clear regulatory guardrails on this matter,” Mr. Eden said in an email. “Otherwise, there will be nothing stopping a future administration from, on day 1, re-instituting the guidance and continuing these secret prosecutions with a vengeance.”

Criticism of the Obama-era directive is nothing new. Conservatives such as U.S. Civil Rights Commissioner Peter Kirsanow and Wall Street Journal columnist Jason Riley have long decried the policy, renewing their calls to have it thrown out after Ms. DeVos was confirmed in February 2017.

“This misguided guidance is having a negative effect on many schools and should be rescinded,” Mr. Kirsanow said in an email. “It derogates rather than promotes orderly learning environments. School disciplinary policy should be driven by common sense and empirical evidence, not racial bean-counting and politically correct fads and slogans.”

Ms. DeVos has shown no love for the Education Department’s Office for Civil Rights’ practice under President Barack Obama of implementing policy by issuing “Dear Colleague” letters, the unsubtle implication being that non-compliant schools could find their funding at risk.

“The era of ’rule by letter’ is over,” Ms. DeVos declared in a Sept. 7 speech, adding that “the prior administration weaponized the Office for Civil Rights to work against schools and against students.”

She followed through that month by withdrawing the 2011 “Dear Colleague” letter on campus sexual violence, which advised universities to use a lower standard of proof for students accused of sexual misconduct, igniting a firestorm among feminists who accused her of protecting rapists.

Her office did not return immediately a request for comment.

The Obama administration may be gone, but its school-discipline guidance is still going strong. Last month, the Milwaukee Public Schools entered into an agreement with the Office for Civil Rights after a three-year federal investigation found the district had reduced its suspensions and expulsions but the racial disparity lingered.

Justice Department attorney Jeremy Thompson recently cited Broward and Miami-Dade as Florida school districts that have experienced “positive outcomes as a result of replacing zero-tolerance policies with restorative justice policies.”

“By adopting programs similar to Miami-Dade and Broward County, other school districts can help eliminate the School-to-Prison Pipeline and decrease the disparate incarceration rates in the U.S.,” Mr. Thompson said in the Feb. 2 edition of the Harvard Law and Policy Review.

Any effort by Mrs. DeVos to overhaul the school-discipline directive undoubtedly would unleash a political outcry.

“It’s almost a certainty that she will get clobbered by this by the education establishment, and it’s possible she’ll get clobbered about it by media establishment,” said Mr. Eden. “It’s my hope that with enough public debate and awareness, it will become, ’The guidance tried to address it, it went too far, and we need a more balanced approach.’”

The 19-year-old gunman opened fire Feb. 14 at Marjory Stoneman Douglas High School in Parkland, killing 17. Mrs. DeVos is scheduled Wednesday to visit the school “to connect with students and teachers.”

“It’s my hope debate on this would shift to the point where the civil-rights advocacy groups will say what they will, but the average American will understand this,” Mr. Eden said.

• Valerie Richardson can be reached at vrichardson@washingtontimes.com.

Please read our comment policy before commenting.