President Trump vowed he would never get snookered into signing another one of Congress’ bloated, budget-busting spending bills, but the resounding response from Washington was “fat chance.”

Longtime budget watchdogs — the same folks whose alarms went mostly unheeded as the national debt nearly quadrupled to $21 trillion over the past two decades — say it’s more likely that Mr. Trump will be gritting his teeth repeatedly and inking his name on more massive spending monstrosities to come.

After all, the same pressures that forced Mr. Trump to sign a $1.3 trillion omnibus spending bill Friday will be just as powerful when the 2019 funding package lands on his desk.

“President Trump shares the same disgust that most Americans have with Congress, and this bill was a perfect example of that,” said Andrew Roth of Club for Growth.

Club for Growth, a Washington advocacy group with a free market and limited-government agenda, urged lawmakers to oppose the omnibus. Their votes will be included on the group’s 2018 scorecard for conservatives.

Despite the president’s good intentions, Mr. Roth said, his “never again” credo will be next to impossible to fulfill.

SEE ALSO: Spending bill draws lines among midterm election candidates

“Most members of Congress — on both sides of the aisle — are paralyzed with the fear of actually passing a real budget. Doing so would require accountability and political courage,” he said. “If Trump promises to veto the next omnibus, and we’ll support him in that effort, he might finally force them to do something that they so desperately don’t want to do.”

This time, to get $80 billion extra for the military, Mr. Trump had to give a $65 billion boost to Democrats’ domestic spending priorities, including $3 million more for the National Endowment for the Arts and the National Endowment for the Humanities. Both are causes that Mr. Trump wants to nix.

Democrats also retained funding for the Corporation for Public Broadcasting, a longtime nemesis of the right.

Mr. Trump didn’t get funding for many of his top priorities. The bill failed to remove funds for Planned Parenthood and sanctuary cities, hire as many border and immigration agents as he wants, and allotted just $1.6 billion for a border wall — far short of the $25 billion the White House requested.

Both sides claimed victories with billions of dollars to combat the opioid addiction epidemic and spending on infrastructure projects, such as $625 million on rural broadband and $2 billion to address the Department of Veterans Affairs maintenance backlog.

Most modern presidents have raised objections to Washington’s big spending, but the money keeps flowing.

SEE ALSO: Special interest groups win big under new spending bill

President Reagan vetoed a transportation bill in 1987 because it contained 152 earmarks, or spending items that lawmakers slip into big bills.

“I haven’t seen this much lard since I handed out blue ribbons at the Iowa State Fair,” Reagan quipped.

Congress overrode the veto.

By 2005, the same bill was packed with 5,671 earmarks.

In March 2009, President Obama lamented the “imperfect” $410 billion bill to fund most of the government through September. He railed against lawmakers for inserting $7.7 billion in earmarks for pet projects.

His solution: earmark reform.

The Republican takeover of the House in 2010, which made Republican John A. Boehner of Ohio the speaker, ushered in an earmark ban that remains in place.

However, massive spending and expanding debt continued.

Mr. Trump pinned the blame on Democrats when he reluctantly singed the 2,232-page bill to fund the government for the remainder of fiscal 2018, which ends Sept. 30.

He said he was caving in to big spending tacked on by Democrats because he received the $654 billion for the military, an $80 billion increase over the previous year.

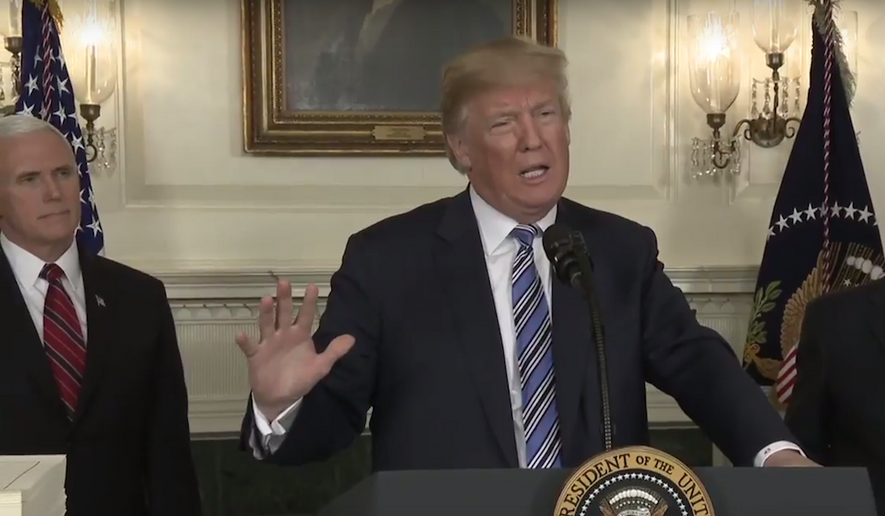

“I say to Congress, ’I will never sign another bill like this again,’” Mr. Trump said, dropping an eleventh-hour veto threat just hours ahead of the deadline to avoid a government shutdown.

He called the legislative process that produced the bill ridiculous.

“It became so big because we need to take care of our military. And because the Democrats, who don’t believe in that, added things that they wanted in order to get their votes,” he said.

Looking for more leverage in the next spending battle, Mr. Trump called on the Senate to eliminate the filibuster and Congress to give him a line-item veto.

Both demands are far-fetched.

Senate Republican leaders have repeatedly balked at Mr. Trump’s calls to end the filibuster rule, which requires 60 votes to advance most legislation.

They argue that it would dramatically alter the nature of the upper chamber by diminishing the role of the minority. The Senate would more closely resemble the virtually unchecked majority rule of the House, a change that Republican leaders say they would regret when they are in the minority.

The line-item veto presents an even bigger hurdle.

Allowing a line-item veto would require a constitutional amendment. The Supreme Court ruled the procedure unconstitutional in the 1998 decision Clinton v. City of New York.

Steve Ellis, vice president of the budget watchdog group Taxpayers for Common Sense, said he would like Congress to follow an orderly appropriations process for next year, but “history and experience leads me to foresee more dysfunction.”

“The total amount of spending for the year was already set by the recent budget deal. But there will be wrangling over individual agency funding levels and various unrelated policy provisions stuck in there. That will complicate considerations,” he said. “As the 2018 election grows closer, these fights will intensify. In September, we will see little has been accomplished and lawmakers on both sides of the aisle kicking the spending-can down the road past the election to avoid a shutdown showdown.”

In other words, Mr. Trump should expect another enormous omnibus bill sometime after the midterm elections.

“The budget deal means it will be more expensive than the last,” Mr. Ellis said. “Add in whichever party feels that it will have the upper hand in the 116th Congress will drag their feet to extract a better deal, which means it will be last-minute, up against a deadline.”

He added, “At that time, President Trump should stick a fork in it and send it back. That said, I have little confidence that he will.”

• S.A. Miller can be reached at smiller@washingtontimes.com.

Please read our comment policy before commenting.