WASHINGTON (AP) - Kentucky native. Single. Oldest of five children. Father was in the Air Force. Johnny Cash fan.

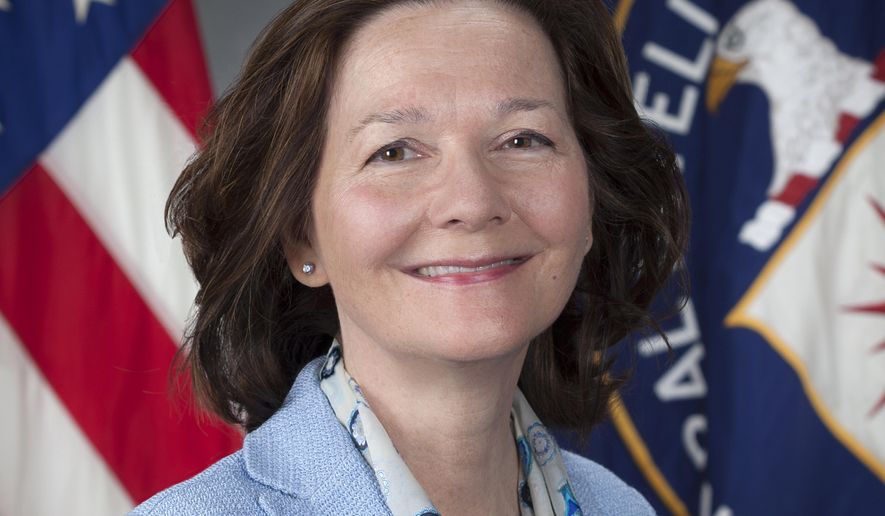

The CIA offered a peek Thursday into the secret life of Gina Haspel, the former undercover agent President Donald Trump has picked to lead the intelligence agency. After 30-plus years at the spy agency, with much of her career classified, Haspel has become best known for leaked details about her time as chief of base of a secret prison in Thailand where terror suspects were waterboarded after 9/11.

In an unusual two-page memo sprinkled with personal tidbits, the agency sought to try to change that before she faces the public spotlight of a confirmation hearing.

The memo about Haspel did not include information about her involvement in the interrogation program. Nor did it address how she drafted a memo that called for the destruction of 92 videotapes of interrogation sessions. Their destruction, ordered by a higher-ranking CIA official in 2005, prompted a lengthy Justice Department investigation that ended without charges.

The memo did offer details about her biography and her taste in office art: A 5-feet tall poster of country music’s Cash.

Haspel, 61, the deputy director of the agency, was born in Ashland, Kentucky. Her father joined the Air Force at age 17 and she grew up on military bases abroad.

“As a junior in high school, Haspel came home and told her dad that she had figured out what she wanted to do with her life: she was going to attend West Point,” the CIA said. “Her dad had to gently break the news to her that West Point did not admit women. The pull of service and adventure, however, stayed with her.”

After graduating high school in Britain, she attended the University of Kentucky where she studied languages and journalism. She’s still an avid fan of the University of Kentucky Wildcats basketball team even though she moved to Louisville, Kentucky, for an internship in her senior year and graduated with honors from the University of Louisville, the agency said.

After college, Haspel worked as a contractor with the 10th Special Forces Group at Fort Devens in Massachusetts. She ran the library and foreign language lab. There, she met a man named Mike Vickers, who went on to become undersecretary of defense for intelligence. It was Vickers who told her about the CIA and she soon learned that it was a place where women could do clandestine work around the world.

“She studied up on CIA, typed up a letter on her college manual typewriter, and sent it off,” the CIA said. “On the outside of the envelope she wrote simply, ’CIA, Washington, D.C.’”

She was hired. Haspel’s first overseas assignment was as a case officer in an undisclosed country in Africa. There she carried out a clandestine mission amid billboards plastered with Marxist-Leninist slogans. She traveled the region, learned to recruit and handle agents, and survived a coup d’etat.

During the first Gulf War in the early 1990s, she worked with other government agencies on humanitarian issues in undisclosed locations. Soon after, she was named chief of station at a small outpost in still another undisclosed location that the CIA described only as an “exotic and tumultuous capital.”

“One night, Haspel received word that two terrorists linked to an embassy bombing, were coming to the country where she was stationed,” the CIA said. “She swiftly put together an operation that led to the terrorists’ arrest and imprisonment, along with the seizure of computers that carried details of a terrorist plot.”

For her work, she received the George H.W. Bush Award for Excellence in Counterterrorism. The CIA didn’t identify the bombing, but in 1998 more than 200 people were killed in truck explosions at U.S. embassies in Tanzania and Kenya.

As the fight against al-Qaida gathered momentum, Haspel requested a transfer to the CIA’s Counter Terrorism Center. She started that job on Sept. 11, 2001, the day terrorists struck the World Trade Center in New York and the Pentagon, killing nearly 3,000 people.

“She walked in amid the commotion, sat down at a computer and got to work,” the CIA said. “She didn’t let up for three years, often working seven days a week.”

Before she was named deputy CIA director last year, Haspel held a series of senior jobs: chief of staff to the deputy director for operations, chief of station in the capital of a major U.S. ally and deputy director of the former National Clandestine Service, which is now called the Directorate of Operations.

Despite her lengthy career, much of Haspel’s upcoming confirmation hearing is expected to be focused on the time she spent supervising the black site in Thailand.

The CIA won’t say when in 2002 Haspel was there, but at various times that year interrogators at the site sought to make terror suspects talk by slamming them against walls, keeping them from sleeping, holding them in coffin-sized boxes and forcing water down their throats - a technique called waterboarding.

No date has been set yet for her Senate confirmation vote.

Please read our comment policy before commenting.