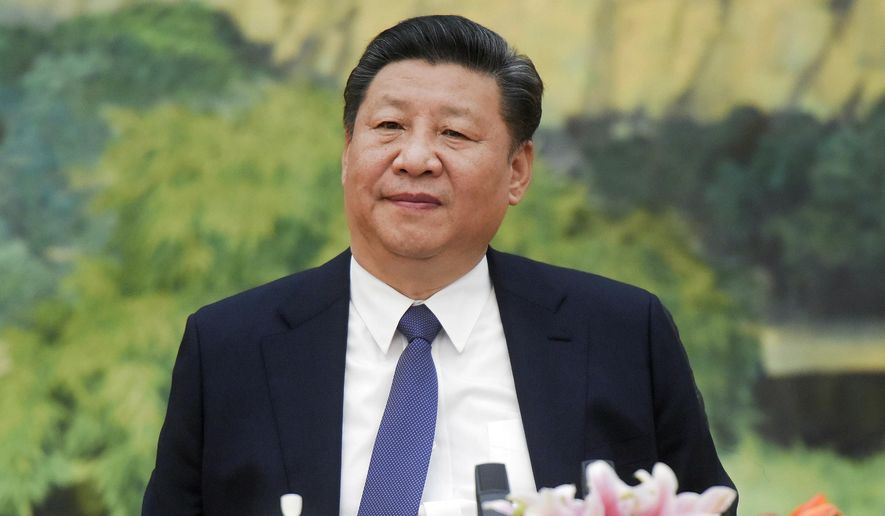

BEIJING (AP) — China’s move to scrap term limits and allow Xi Jinping to serve as president indefinitely puts him on track to deal with some of the country’s weightiest long-term sovereignty challenges, especially the fates of Hong Kong and Taiwan.

The question is, will Xi bet big on bold moves that could result in potentially disastrous consequences?

Hong Kong offers a delicate initial test. Since passing from British to Chinese rule in 1997, the financial hub has operated as a “special administrative region,” retaining its own legal and economic system and enjoying a considerable degree of autonomy from Beijing.

That arrangement was supposed to last 50 years, until 2047, but calls for political reform in the city and what many see as Beijing tightening its controls and encroaching on freedoms there have created rising tensions.

Earlier this month, a member of the all-powerful Politburo Standing Committee delivered a stern warning to Hong Kong delegates to China’s rubber-stamp parliament over the central government’s limits of tolerance.

“Using the high degree of autonomy to reject, fight and erode the central government’s comprehensive jurisdiction is absolutely not allowed,” Zhao Leji told members of the National People’s Congress, which passed a constitutional amendment Sunday abolishing presidential term limits, opening the door for Xi to rule for as long as he wants.

Hong Kong activists had already been set on edge by the disqualification of pro-democracy lawmakers from the city’s Legislative Council and the apparent abduction by Chinese security forces of several men who published salacious tomes about China’s leadership.

Still, Hong Kong remains one of the world’s freest economies and a window to the outside for the Chinese financial system, which operates under much tighter restrictions. The cosmopolitan city of 6 million, with its vibrant tourism, arts and education sectors, also remains a beacon to many aspiring Chinese.

“I don’t think bold action is necessary with respect to Hong Kong,” said Michael Mazza of the American Enterprise Institute think tank in Washington, D.C.

Xi is “already well along in the process of turning (Hong Kong) into just another Chinese city,” he said.

Self-governing Taiwan, however, is quite a different story, posing a direct challenge to the Communist Party’s claim as the representative of all Chinese and guardian of Chinese sovereignty, independence and territorial integrity.

Since splitting from the mainland amid civil war in 1949, the former Japanese colony has evolved into a wealthy, vibrant democracy whose 23 million people take an increasingly dim view of any form of political integration with Beijing.

By casting himself as a leader of historic standing, Xi has assumed the mantle of unifier and may regard failure in this regard as a stain on his reputation. In his most direct comments on the issue, he told a Taiwanese envoy in 2013 that a final resolution was required, and that what he regards as the “sacred mission” of unification “cannot be passed on from generation to generation.”

“Action on Taiwan is certainly possible. Unification is a key aspect of Xi Jinping’s goal of ’national rejuvenation,’ necessary for achieving the ’China Dream,’” Mazza said, referencing two of Xi’s chief goals.

Xi “may conclude that peaceful unification is not in the cards any time soon, leaving him to rely on coercion or outright force to achieve his goals,” he said.

Already, China over the past two years has been ratcheting up political, diplomatic and economic pressure on Taiwan’s independence-leaning president, Tsai Ing-wen.

A military attack, however, could quickly draw in the U.S., which is legally bound to respond to threats against the island.

Yet the risks of an attack on Taiwan remain prohibitively high, to the point of threatening regime stability in China, due in no small part to its embrace by the U.S. and Japan, said Miles Yu Maochun, a China politics expert at the U.S. Naval Academy. Hong Kong, meanwhile, remains too valuable to Beijing in its present form to risk upsetting, he said.

Xi views Taiwan and Hong Kong as equally important to cementing his authority, said analyst Teng Biao, a visiting scholar at New York University’s U.S.-Asia Law Institute.

“When he has strengthened his own power, he will show zero tolerance for Taiwan and Hong Kong independence, and even more threaten the use of force,” Teng said.

While it is broadly assumed that an increasingly dictatorial Xi will also grow more aggressive on the world stage, it’s unclear how that will manifest itself. China says it is committed to seizing a group of uninhabited flyspeck islands in the East China Sea from Japan, but is also aware that such action would trigger the U.S.-Japan security alliance.

And despite President Donald Trump’s “America first” policy and his withdrawal of the U.S. from the Trans-Pacific Partnership, Washington and its armed forces show no sign of giving up the West Pacific to China.

While Xi’s position appears unassailable, domestic political risks remain that may prompt him to take an even harder line at home and abroad, said Teng, who was detained by Xi’s regime while working as a human rights lawyer.

“When the Communist Party faces political, economic and ideological challenges, and given the fact that the party firmly refuses a democratization, the only way seems to become more dictatorial and oppressive,” Teng said.

Please read our comment policy before commenting.