OPINION:

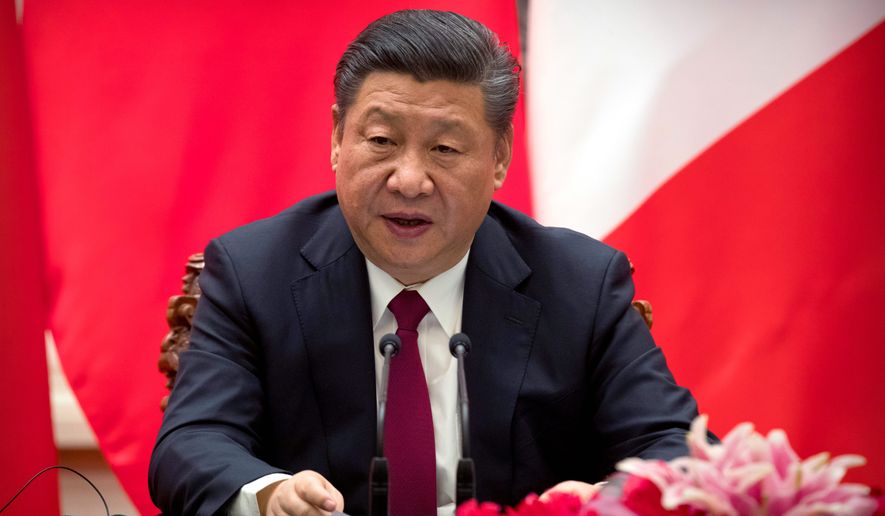

For most heads of state in democratic countries, getting two out of three things you want is pretty good going. But China does not pretend to be a democratic country, and Xi Jinping, the president, does not pretend — seriously, anyway — to be a small-d democrat. He has set out to make it three out of three, and who’s to say he won’t.

Mr. Xi, who aspires to leadership on the world stage, currently serves at the apex of the Chinese political system — he controls the Chinese Community Party, the People’s Liberation Army, and the state. Control of the state, which grants him the title of president, is arguably the least important of the three. In China, control of the Communist Party and the Chinese military trump all else.

Mr. Xi, 64, was scheduled under the rules, such as they may be, to give up his role of president after serving two consecutive terms. Chinese presidents have served two terms, the idea being to avoid the chaos that a long-serving Mao-style leader might bring down. Even though Mr. Xi would have given up the presidency in several years time, under the prevailing rules he could have maintained control of the party and the military long past 2023.

However, so it has been announced, the National People’s Congress of the Communist Party will “recommend” next week that term limits be scuttled as regards the president and vice president, and that sets up Mr. Xi to be president and everything else for life.

Mr. Xi’s decision speaks to both his strengths and weaknesses. His decision is based in part on fear. In his first term he initiated a wide-ranging crackdown on corruption, and, hardly coincidentally, this included cracking down on his enemies. More than a million Chinese military and party leaders were “disciplined” during Mr. Xi’s first years in office. If he steps down from the presidency, many of those enemies would look forward to settling scores.

Mr. Xi appears to be paranoid about the reaction of the Chinese people. After the announcement that term limits would be trashed, his Internet censors went to work, banning phrases such as “I disagree” from China’s heavily patrolled social networks. So was the phrase, “boarding a plane,” because that sounds similar in Chinese to “ascending the throne.” Some of the forbidden names and phrases seem as ludicrous to outsiders as putting sugar in Szechuan chicken seems in Chinese kitchens. Winnie the Pooh is exiled because Mr. Xi has often been likened to the cartoon bear. Forbidden are the words “emperor,” “lifelong” and “shameless,” because somebody might imagine they apply to Mr. Xi.

The most curious forbidden indulgence is expressing dissent mathematically, as in the formula “N > 2,” because the letter N represents the number of Mr. Xi’s terms in office. Nobody has ever accused the Chinese of being less than subtle. The paranoia may be justified. The editor of the China Digital Times, an independent Web news site, observes that “censored terms are the best evidence for what people are talking about.”

Curious it may be, but it cements Mr. Xi’s role as the most powerful leader since Chairman Mao. In 2016, Mr. Xi was designated China’s “core leader;” in modern China, only Mao and Deng Xiaoping have held that title. Last year, he was even written into the Chinese Constitution: “Xi Jinping Thought on Socialism with Chinese Characteristics for a New Era” is now the official political doctrine of the nation. “China cannot stop and take a break,” one newspaper thunders, “The country must seize the day, seize the hour.”

A personality cult not seen since the Mao days thrives. Mr. Xi’s rule has meant a vicious and wide-ranging crackdown on civil society, which is particularly striking after the comparatively liberal reign of his predecessor, the bland functionary Hu Jintao. Scores of lawyers have been detained.

Abroad, Mr. Xi has put paid to the optimistic narrative about China’s “peaceful rise.” He has dispatched Chinese naval vessels into disputed territories in the East China Sea, prosecuted border disputes with Japan and India, bullied Taiwan and South Korea, and built artificial islands in the South China Sea intended to become military bases.

He has not done nearly enough to curtail the nuclear ambitions of China’s official ally, North Korea, which is his unofficial thumb in the eye of the rest of the world. His Belt and Road initiative intends to link China with Central Asia and Europe, which attempts a wildly ambitious reshaping of the global economic order. But despite his serene confidence, shaping such a new order to a Chinese recipe may be more expensive than he anticipates.

Please read our comment policy before commenting.