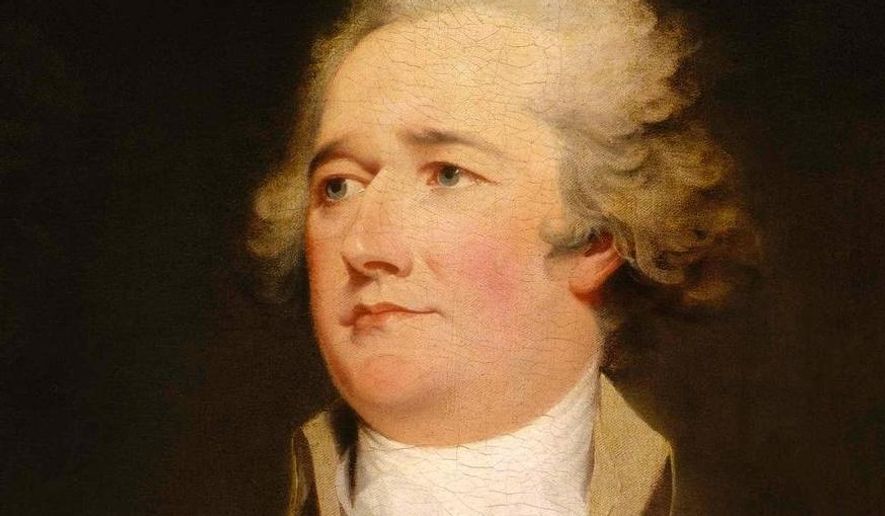

Alexander Hamilton has inspired a Broadway smash, a best-selling cast album and a become household name, thanks in no small part to composer/lyricist Lin-Manuel Miranda’s “Hamilton: An American Musical.”

Now the Founding Father is taking his shot in a new exhibit at the National Archives.

“Alexander Hamilton: An Inspiring Founder,” which opened Thursday at the Archives, doesn’t just feature original letters and official documents by Hamilton: The exhibit juxtaposes “Hamilton” lyrics with the documents they reference.

“Many of Hamilton’s economic, political, and military ideas for the new United States of America became vital to its future success, yet his story has been retold less often than those of other Founders,” the Archives announced in a press release.

In reference to the original petition by Elizabeth Hamilton, his wife, to preserve and publish his writings, the Archives captured the purpose of appealing to a young audience through the lyrical exhibit.

“She argued that publishing and preserving his papers would demonstrate to the American people how necessary Alexander Hamilton was to the nation,” the Archives said.

On Thursday, hundreds of young students visiting the museum — some from Washington schools, some from out of town — were absorbed by the Hamilton exhibit.

But not all historians laud “Hamilton” for its youth appeal. Lyra D. Monteiro, a professor of early U.S. history and ethnic identity at Rutgers University, said the exhibit “strikes me as yet another, and in some ways very predictable, extension of this trend where basically anyone involved in public history work are capitalizing on the popularity of the musical.”

While Ms. Monteiro appreciates the Miranda-penned show for its music, she said it pushes a problematic narrative.

“The history that comes out in the musical is frankly the old-school narrative of the American past [that] this country was established by very, very wise, great white men, and they wanted to create a place where we could all be equal,” she said.

Still, students pored over the Hamilton documents and enjoyed that the exhibit included lyrics.

“I was surprised when I came over, I didn’t think that it would have anything to do with the musical,” said Katelyn Wackrow, an 18-year-old from Boston who graduated from high school this month. “But I think it shows that the musical helped him to become more known. Before, there wasn’t a lot of stuff dedicated to him, but now it’s a popular attraction, clearly.”

Ms. Wackrow and her friends could hardly satisfy their attraction to the musical when they first heard it.

“A bunch of my friends were obsessed with it and played it, and I had no idea what it was” when she first listened to the album two years ago, Ms. Wackrow said, adding that the more she listened, the more she loved it.

Was she obsessed, too? “Slightly,” she said.

Despite the musical’s popularity, Ms. Monteiro has declined to embrace it because, she says, it hurts the Black Lives Matter movement more than it helps it.

“Hamilton is hip-hop lite,” she said, which permits white liberals to think “I’m not racist for not dealing with [the Black Lives Matter] because, look, I like ’Hamilton.’”

Still, Ms. Wackrow said the Hamilton exhibit matters and so does the story it conveys.

“[The original documents] say how he went and he talked for six hours, and he was relatively unknown, so it’s kind of a big deal — this unknown guy, he had big aspirations, he started to make a name for himself,” said the high school graduate.

The Hamilton documents rest in the East Rotunda Gallery near the entrance to the Rotunda, where the original Declaration of Independence, Constitution and Bill of Rights lie. The exhibit runs through Sept. 18.

Please read our comment policy before commenting.