OPINION:

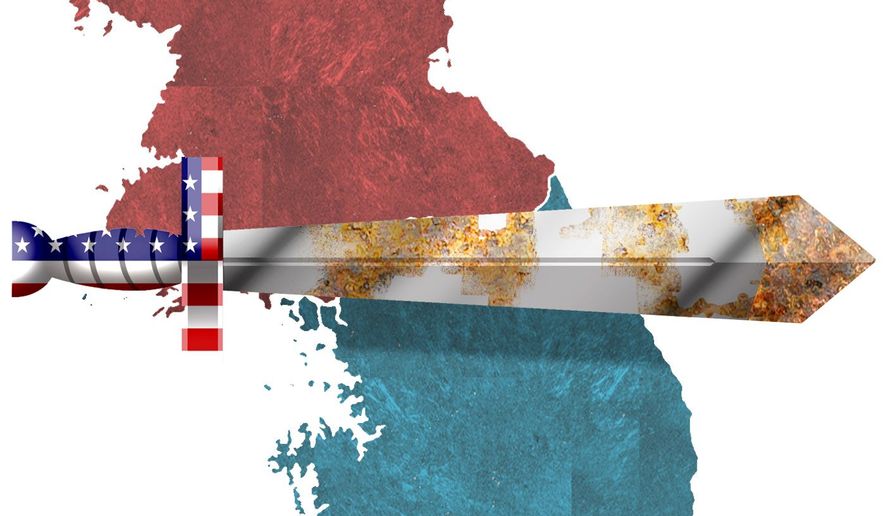

Cancelling large scale combined military exercises in South Korea while the details of the Trump-Kim peace process are being worked through is a calculated risk, but it is probably worth the effort. This is particularly true if a formal agreement to end the nearly seven-decade war in Korea is achieved.

Since 1953, that war has been in an uneasy truce, but it is still a war. Until real confidence-building measures between the two Koreas and the United States are implemented, the coalition is wise to keep up its guard. This can be done without large scale exercises if some innovation and imagination are applied. The demolition of some North Korean nuclear and missile test sites and the suspension of large scale South Korean exercise are a good start.

Large exercises are usually designed to keep current on three key military functions. The first is command and control — that is the ability to make sure communications work — and ensure that the language barrier between the South Koreans and their English-speaking allies is not a show stopper. Korean defense is still a U.N. function, although the U.S. provides the overwhelming proportion of U.N. troops in Korea.

Second, exercises practice the ability to rapidly deploy reinforcements from outside Korea by sea and air in the event that a conflict breaks out. Finally, exercises allow the forces that might be called upon to defend the South to familiarize themselves with the terrain over which they might be fighting. All of these can be done without large scale exercises if a little imagination and innovation is exercised.

Command and control can be practiced through frequent communications exercises between the major headquarters involved in war plans. In addition, computer-generated war games between the major headquarters that would be involved in a conflict don’t have to be held in Korea. The South Korean key players could be flown to the U.S. or Japan so as not to unduly aggravate the North in ongoing negotiations.

The arrival and assembly of reinforcements called for in any war plan can likewise be practiced outside the Korean peninsula. The process of unloading the Marine Corps’ equipment from Maritime Prepositioned Ship squadrons and fast Army sea lift is not remarkably different for a conflict in Korea than anywhere else.

Situational awareness of the terrain is likely the only thing that needs to be done on the peninsula itself, but that can be accomplished by using some imagination. The commanders and key staff of units designated in the war plans to reinforce Korea can familiarize themselves with staff rides or tactical exercises without troops — TEWTs in military parlance. These can even be done in civilian clothes.

Students from our command and staff and war colleges routinely visit Civil War, World War I and II battlefields as part of their curriculum. There is no substitute for knowing the terrain that you might have to fight in. Gen. Patton had thoroughly walked French and German terrain in his off-duty hours as a student at the French War College and credited those outings as largely contributing to his military success. Such activities should not disrupt negotiations if the North Koreans are serious about pursuing peace.

The real concern that American military planners should have with combat readiness in Korea has nothing to do with large scale exercises on the Korean Peninsula. After nearly two decades of combat in low-level counterinsurgencies, many active duty and retired military observers are concerned with the ability of U.S. units to fight in heavy conventional combat.

In a recent international tank-firing competition, American Army crews came in a dismal seventh, beating out only Ukraine. The Russians, Chinese and Koreans did not participate. Army and Marine Corps units are now beginning to restart exercises that replicate intense conventional combat at their training facilities in the California high desert that were replaced by counterinsurgency exercises at the height of the wars in Iraq and Afghanistan. That should eventually improve readiness for the kind of combat they would face in Korea.

President Trump believes that Kim Jong-un is serious about wanting peace. However, until we see concrete evidence such as withdrawing thousands of artillery pieces in range of the South Korean capital, the allies are well advised to hope for the best and prepare for the worst. Even if Mr. Kim is sincere, a coup by hardliners could bring us back to the bad old days of the pre-Trump-Kim summit. President Reagan was right when he declared; “trust but verify.”

• Gary Anderson is a retired Marine Corps colonel with extensive experience in Korean exercises. He lectures on war gaming at the George Washington University’s Elliott School of International Affairs.

Please read our comment policy before commenting.