BUENOS AIRES — When Nicaraguan guerrilla leader Daniel Ortega first took power in mid-1979, his admirers included a 17-year-old Caracas high school dropout who celebrated a “newly lit light” in Latin America as he maneuvered his bus around Venezuela’s hilly capital.

Nearly four decades down the road, the driver, Nicolas Maduro, clings to power as his country’s embattled president, and it seems to be the increasingly unpopular Mr. Ortega who is taking cues from his Venezuelan counterpart as he tries to hold on to power.

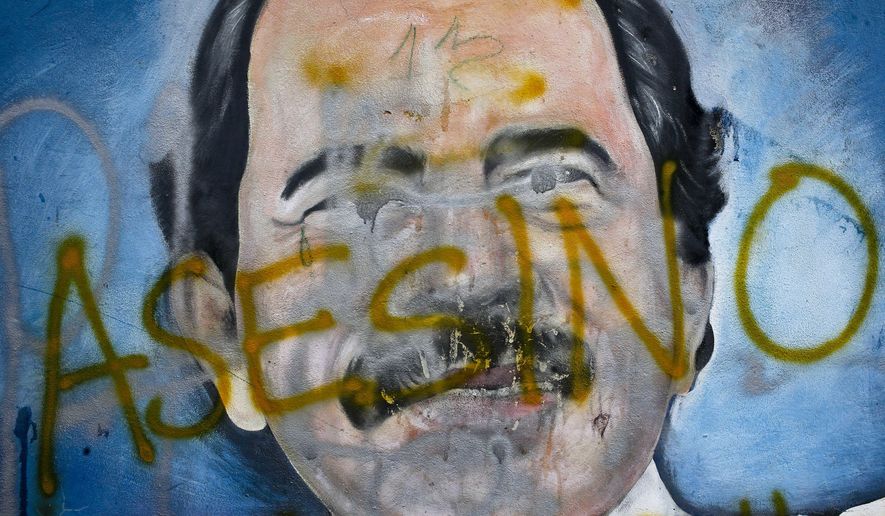

It has been a stunning comedown for Mr. Ortega, who led the anti-U.S. Sandinista movement in the Reagan era and seemed so secure in power two years ago that he engineered the election of his wife as vice president in a landslide electoral win.

All that has changed since an outbreak of popular discontent in April. It is so severe that some warn of a coup and others fear the country could face another civil war.

Faced with nationwide protests — initially over a pension reform but rapidly expanding against his autocratic rule overall — Mr. Ortega has led a violent clampdown, with security forces and paramilitary forces killing an estimated 297 demonstrators in less than three months. That number exceeds the deaths from political protests in Mr. Maduro’s Venezuela in the same period.

It’s not a stretch, then, that Mr. Ortega may be borrowing a page from his Venezuelan ally’s playbook, Stephen Kinzer, a senior fellow at Brown University’s Watson Institute for International and Public Affairs, told The Washington Times.

“I think he probably is looking at the Maduro example and thinking to himself, ’This guy survived for years even though most of the people in his country are rebelling against him. I can do the same thing,’” said Mr. Kinzer, author of the classic “Blood of Brothers” account of Nicaragua’s 1980s civil war.

Absent a viable exit strategy, holding on to power, whatever the cost, may seem like the only viable road to the 72-year-old leader, who remained Nicaragua’s dominant political figure even during a 17-year hiatus starting in 1990 when he did not hold high elective office, Mr. Kinzer said.

The analyst said the situation is particularly dangerous because Mr. Ortega appears to have few options other than trying to brazen it out.

“What’s the alternative for him? Don’t forget that over all these tyrants like Ortega hangs the threat of accountability,” Mr. Kinzer said. “Once you’re out, you no longer control the courts, you no longer control investigators or the police, [and] everything is going to come out.”

For the time being, though, Mr. Ortega and his wife and vice president, Rosario Murillo, remain firmly in control. In a show of strength on Tuesday, they dispatched hundreds of police and paramilitary fighters to the towns of La Trinidad and Jinotepe, where students and farmers had set up roadblocks as part of the anti-government protests.

The forces used live ammunition to fire on the demonstrators, causing an unknown number of injuries, local human rights activists told the DPA wire service. Mr. Ortega celebrated the assault as “good news for trucks and trailers.” He noted dryly that “traffic in that zone has been normalized.”

But signs are growing that the president’s position has been shaken. Former President Enrique Bolanos has called on Mr. Ortega to step down, and even the president’s brother, Humberto Ortega, a former head of the army, called this week on his brother to hold early elections next year and to restrain the pro-government youth groups that many blame for provoking the violent street clashes of the past three months, The Associated Press reported Thursday.

Popular unease

But the leader of the Sandinista National Liberation Front may be overplaying his hand, said Pedro Joaquin Chamorro, who, as a member of one of the country’s most storied political clans, served as a leader of the U.S.-backed anti-Sandinista Contras and later in various Cabinet posts, including defense minister.

Popular unease over Mr. Ortega’s authoritarianism had long been brewing, Mr. Chamorro told The Times, but the staggering level of violence shook up Nicaraguans used to a quarter-century of relative calm, particularly compared with their Central American neighbors in El Salvador, Guatemala and Honduras.

“If Daniel Ortega hadn’t turned to repression, to violence against peaceful demonstrators, nothing would have happened,” he said. “[But with] blood spilt in the streets of Managua, the murders of children, of youngsters, of students — and to continue it instead of stopping it — the thing has already turned irreversible.”

Mr. Chamorro, whose father’s 1978 assassination sparked the Sandinista Revolution and whose mother, Violeta Chamorro, defeated Mr. Ortega in the 1990 presidential elections, now has his hopes pinned on Catholic Church-mediated talks, which resumed late last month after initial setbacks.

Leadership surrounding Cardinal Leopoldo Brenes, Managua’s archbishop, who this week in Rome briefed Pope Francis on the negotiations, has reportedly been quite forward in pushing for presidential elections as early as March.

Although not inclined to leave either quickly or quietly, Mr. Ortega also may no longer hold the political capital to serve out his term, nominally set to end in 2021, said Christine Wade, a political scientist at Washington College in Chestertown, Maryland.

“The government has accepted [the church] as mediators,” Ms. Wade, a co-author of “Nicaragua: Emerging from the Shadow of the Eagle,” told The Times. “[And] early elections is probably the best-case scenario for the protest movement at this point, because I don’t anticipate that he’s simply going to resign.”

But as Nicaraguans and foreign policymakers alike try to gauge the intentions of Mr. Ortega, Ms. Wade cautions against painting the Nicaraguan leftist with the same brush as Mr. Maduro or his mentor, the late anti-U.S. populist Hugo Chavez.

“Ortega was around far before the likes of Hugo Chavez emerged, [and] unlike Maduro, I would expect an Ortega as probably weighing his legacy and the legacy of the revolution at the same moment,” she said. “Thinking about an exit strategy is something they’re probably doing with some seriousness.”

Still, old habits die hard, Ms. Wade said, and the situation will likely get worse before it gets better.

“We’re dealing with an administration that’s battle-hardened: These are old-guard revolutionaries. They fought and won wars.

“There’s a bit of a siege mentality that is part of the current thinking.”

History lesson

Old history — as in the often-troubled ties between Nicaragua and the United States — could prove a factor as the U.S. government ponders how to approach the Nicaraguan crisis. Less will be more in this conflict, virtually all observers agree.

“I’d love to see the United States take its hands off Nicaragua,” Mr. Kinzer said. “We will completely delegitimize this great, peaceful social movement if we barge into it.”

The Trump administration, which is reportedly considering duplicating its sanctions on Maduro officials with high-ranking government officials in Nicaragua, should tread lightly so as not to provide fodder to those aiming to distort legitimate protests as imperialist meddling, Ms. Wade said.

“Back-channel discussions are helpful, public condemnations of violence are appropriate, but overall, the United States would do very well to keep a low profile in this particular conflict,” she said. “We’ve already seen that there are forces … trying to say, ’This protest movement is another U.S. destabilization attempt.’”

Even if the situation further deteriorates, Ms. Wade said, it’s unlikely that the United States will see an influx of refugees from Nicaragua the way violence and gang wars have sparked an exodus from other Central American countries, because Nicaraguans fleeing violence would be more likely to seek shelter in Costa Rica or Panama.

For other regional players, Nicaragua’s powder keg may even present an opportunity, Mr. Kinzer said. The Organization of American States, long viewed as toothless, could play a role, he said, as could Mexican President-elect Andres Manuel Lopez Obrador.

Another regional group, the Inter-American Commission on Human Rights, announced this week that a team of independent investigators had set up in Nicaragua to investigate political violence that has rocked the country since April.

There may be ideological overlap between Mr. Ortega and Mr. Lopez Obrador, Mr. Kinzer said. But unlike his Nicaraguan counterpart, Mexico’s incoming president has always respected the electoral process and has made a number of pragmatic moves since his electoral triumph, he added.

“Ortega is just the opposite of that, so the idea that [Mr. Lopez Obrador] would be an instinctive ally of Ortega is a big stretch,” he said. “He could definitely posit himself as a person whose own background requires him to condemn what’s happening in Nicaragua.”

Whether such condemnation, renewed protests or mediation talks can ultimately keep Mr. Ortega from trying to use the Maduro model to hold on to power, meanwhile, remains to be seen. But perhaps one can count on its size to shield this compact nation of 6 million from becoming a second Venezuela, Mr. Kinzer said.

“Everybody in Nicaragua has a sense of being cousins; they all know each other,” he said. “There’s a sense of shared destiny, and I hope that will somehow contribute to some resolution of the problem.”

As Mr. Ortega knows well, it would not be the first time Nicaraguans rid themselves of an autocratic leader.

“The battle cry of the Samoza era is what people are now chanting in the streets,” Mr. Chamorro said. “It was: ’Nicaragua will be a republic again!’”

Please read our comment policy before commenting.