OPINION:

Not so long ago, freedom and democracy seemed to be on the march in the world, with Turkey and Pakistan, two strategically important Muslim-majority nations, near the front of the parade. That turns out to have been an illusion. Elections recently held in these countries have, paradoxically, made that clear.

In Turkey, votes cast in June gave President Recep Tayyip Erdogan powers he has long coveted. He is now, effectively, head of state and government, the military and the judiciary. For quite some time now, he also has been censoring the media, instructing private industry and filling his jails with enemies and dissidents.

Brick by brick, he is dismantling the legacy of Mustafa Kamal Ataturk, who founded the Republic of Turkey in 1923 following the collapse of the Ottoman Empire, and whose goal was the creation of a modern and secular nation-state.

Mr. Erdogan is increasingly allying with anti-American autocrats, in particular Russian President Vladimir Putin, notwithstanding Turkey’s membership in NATO, and the rulers of the Islamic Republic of Iran, whom he has helped evade sanctions.

Adding insult to injury, Mr. Erdogan has been holding an American citizen hostage. Andre Brunson, pastor of a small Christian church, has been accused of “Christianization using religious beliefs and sectarian differences to divide and separate the Turkish people.”

What the Turkish president apparently wants is to trade Pastor Brunson for Muhammed Fethullah Gulen, a political rival living in exile in the United States. The fact that Mr. Gulen appears to have broken no laws is just one reason it would be awkward for American authorities to acquiesce.

As for Pakistan, it was born in 1947 as an independent homeland for Indian Muslims unwilling to live as a minority in a Hindu-majority nation. Pakistan’s founder, Muhammad Ali Jinnah, envisioned a polity that would guarantee human and civil rights to all its citizens - Hindus, Sikhs, Christians, Ahmadis and others.

“Islam and its idealism have taught us democracy,” he said in a 1948 radio address. “It has taught equality of man, justice and fair play to everybody.”

His dream has not been realized. Pakistan has spent much of its brief history under military rule. In the 1980s, Gen. Zia-ul-Haq began a process of Islamization which, over time, has become increasingly obscurantist and intolerant.

For the past decade, civilians have been in charge and there was a peaceful transition of power in 2013. But elements within the military and intelligence services have continued to pull the strings from behind the curtain.

Farahnaz Ispahani, a former Pakistani legislator now at the Woodrow Wilson Center for International Scholars in Washington, is not alone in believing that last week’s elections were marred by “media censorship, arbitrary disqualifications of leading candidates, manipulation of political parties by intelligence services, and the mainstreaming of terrorists.”

The winner was 65-year-old former cricket star Imran Khan and the political party he founded in 1996, Pakistan Tehreek-e-Insaf (PTI). Ms. Ispahani characterizes Mr. Khan as “the Pakistani equivalent of Turkey’s Erdogan.” She adds that he has “earned the military’s trust.” She is not paying him compliments.

The worldview of Mr. Khan, writes Sadandand Dhume, a resident fellow at the American Enterprise Institute, “blends the laziest leftist cliches with absurd Islamist fictions.” Mr. Khan “supports fundamentalist positions, including a cruel blasphemy law that leaves religious minorities vulnerable to lynch mobs.”

Mr. Khan’s “signature economic idea,” Mr. Dhume adds, “to turn Pakistan into an Islamic welfare state, belongs in a fairy tale,” given the debilitated state of the Pakistani economy after generations of mismanagement and corruption.

During the campaign, Mr. Khan said: “Pakistan must detach itself from American influence and pull out of the ’war on terror’ in order to create prosperity and achieve regional peace.”

In fact, Pakistan has long been an ambivalent participant in that war. On the one hand, we are permitted to use Pakistani territory to resupply our troops in Afghanistan. On the other hand, as Bill Roggio, my colleague at the Foundation for the Defense of Democracies, and the editor of FDD’s Long War Journal, puts it:

“Pakistan has accepted billions of American dollars, and used those funds to provide safe havens for the Taliban and other jihadist groups. Pakistan is directly responsible for the killing and wounding of thousands of American and allied soldiers.”

You’ll recall that Osama bin Laden found refuge in Pakistan until U.S. special operators arrived unannounced at his villa. The claim that no Pakistani authorities knew he was in Abbottabad — a garrison town not far from Islamabad, Pakistan’s capital — is risible.

Mr. Dhume also has reported that recently “a signatory of Osama bin Laden’s 1998 declaration of jihad against ’the Jews and Crusaders,’ joined Khan’s Pakistan Tehreek-e-Insaf party.”

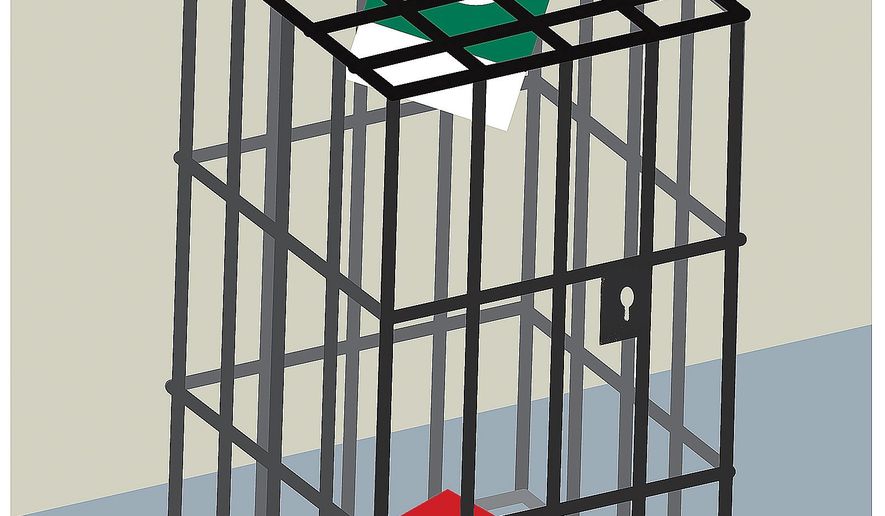

So to sum up: Elections in both Turkey and Pakistan have strengthened not democracy, but authoritarianism and Islamism. In both countries, freedom is not expanding but diminishing. Both countries have leaders who cannot be counted on to stand with Americans against those who might be seen as common enemies.

I’m not arguing against elections. I am arguing that elections alone do not necessarily give rise to liberal democracy — or even decent governance. In countries that have not developed democratic institutions and habits, voters are apt to choose leaders contemptuous of religious freedom, freedom of the press and minority rights. Nor will a majority of voters disqualify politicians who condone terrorism that suits their purposes.

This is a serious dilemma for Washington policy makers; even more so for the millions of Turks and Pakistanis who aspire to freedom and prosperity, and must now realize that their homelands will achieve neither anytime soon.

• Clifford D. May is president of the Foundation for Defense of Democracies and a columnist for The Washington Times.

Please read our comment policy before commenting.