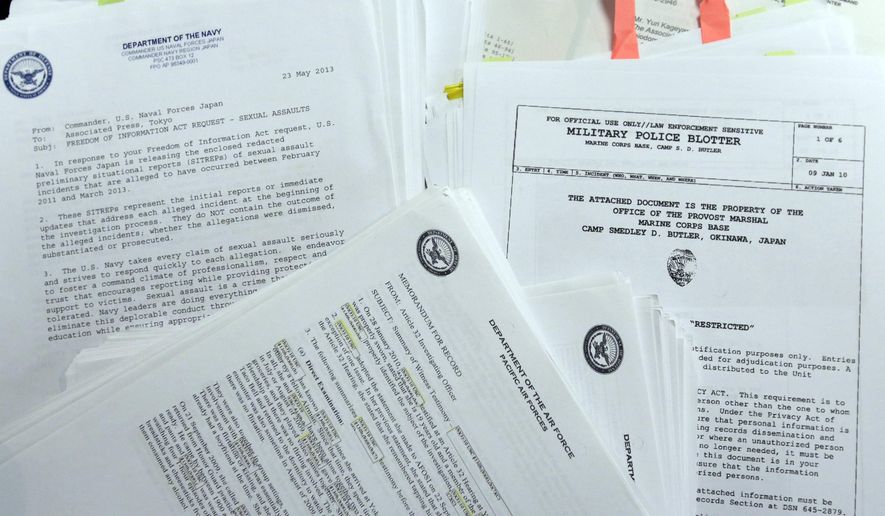

The federal Freedom of Information Act was supposed to give the public relatively quick and easy access to the very government documents their taxes paid for — but the system is increasingly broken, with some agencies still working on requests filed some 20 years ago.

At least five federal agencies have unfulfilled FOIA inquiries spanning more than a decade, according to a Washington Times review of two dozen of the largest agencies.

Despite recent initiatives to prevent FOIA requests from piling up, watchdogs who rely on it to hold the government accountable say nothing has changed.

“It is about the same, which is to say terrible,” said Nate Jones, director of the Freedom of Information Act Project for the National Security Archive, a nonprofit that researches international affairs and stores declassified government documents.

The most recent annual FOIA reports filed by 24 large agencies show even routine records requests can take years to complete. The reports, issued last year, collect data through the fiscal year ending on Sept. 30, 2016.

The National Archives and Records Administration’s report showed it had an unprocessed FOIA request from 1993. However, Gary Stern, NARA’s general counsel and chief FOIA officer, said that request has since been resolved. Now the agency’s longest pending inquiry dates back to 1998.

The Department of State, the Central Intelligence Agency and the Department of Defense have outstanding requests from 2006. The Department of Energy, a smaller agency, has a backlog that stretches to 2007, and the Department of Commerce, which received only 454 requests in fiscal 2016, has yet to process one from 2011.

Overall, the government received a record 789,000 requests last fiscal year but processed only about 760,000, according to the Department of Justice. Of the 24 reports reviewed by The Washington Times, 16 agencies processed fewer requests than they did in 2015.

“We have FOIAs that go back to our existence as an entity in 2011,” said Lee Steven, assistant vice president at the Cause of Action Institute, a limited-government advocacy group. “We just decided to stop pursuing them because they’ve never been answered.”

On average, it took the 24 agencies about 42 days to process requests they designated as simple. But 11 agencies needed more than 1,000 days, or roughly three years, to fulfill some of the simple records searches. Complex requests were completed in an average of 189 days, but 12 agencies spent 1,000 days for some inquiries and four agencies took as long as four years for others.

Trump upholds Craig memo

It’s not just the delays. The government has been censoring or outright denying access to files at a furious pace. In each of the past three years, the Obama administration set a record for rejecting and redacting documents, according to an Associated Press study.

Materials were censored or denied in 466,165 cases in 2014; 596,095 cases in 2015; and 607,352 cases in 2016, the AP found. The administration also spent a record $36.2 million in 2016 to fight FOIA requests in court.

The 24 agencies reviewed by The Washington Times fully denied 240,901 requests but fully granted only 144,379 inquiries.

“The Obama administration was terrible,” Mr. Steven said. “They were not really forthcoming and obstructed FOIA in a number of ways.”

A murky 2009 memorandum sent by Obama administration attorney Greg Craig encouraged agencies to deny rather than release documents. It required agencies to consult with the White House before releasing any documents that might involve “White House equities.” The letter never fully defined “equities.”

Government watchdog groups, including Cause for Action, demanded that President Obama clarify the policy, but he never did.

“It allowed the White House to intrude on the FOIA process anytime there was anything of interest,” Mr. Steven said.

Some had hoped President Trump would reverse this policy, but Ashley McGowan, a spokeswoman for the Department of Justice, confirmed the Craig memorandum will remain in effect. Ms. McGowan said it is a long-standing practice for agencies to consult with the White House on requests that involve its equities.

The Trump administration, like its predecessor, has yet to define what “equities” means in the FOIA context. But the effect is clear: Journalists and citizens face new hurdles in learning what their government is up to.

Patrick Llewellyn, an attorney with the nonprofit advocacy group Public Citizen, fears the Trump administration will roll back transparency further. Since President Trump took office, he said, some agencies stopped releasing documents on their websites, while others have removed important records.

Less than two weeks into the Trump administration, the Department of Agriculture removed from its website thousands of documents detailing animal welfare violations at zoos, breeders and farms. The Environmental Protection Agency no longer posts climate change information on its home page.

“The agencies could save themselves time and effort by proactively posting information they know people are going to request,” Mr. Llewellyn said.

As backlogs and redactions accumulate, so do appeals and court cases. In some cases, appeals take longer than the FOIA request itself. Some agencies have administrative appeals dating back to 2006.

Appeals can be somewhat effective. Last year, the government admitted it was wrong to withhold access in one-third of the cases, its highest rate in six years, according to the AP study. But it still pushed to deny records, forcing citizens, journalists and watchdog groups to pursue litigation.

The number of FOIA cases filed in federal court reached an all-time high of 498 in fiscal year 2015, a Syracuse University study revealed. In fiscal years 2014 and 2015, a total of 919 FOIA cases were filed, a 54 percent increase from the 595 matters filed during fiscal years 2009, and 2010, the first two years of the Obama administration.

In the final two years of the George W. Bush administration, 562 FOIA lawsuits were filed.

“Very rarely did we file lawsuits,” Mr. Jones said. “But in the past year, it has been increasing. Unless you file a lawsuit, you are going to have to wait more than five years. The system is getting so much worse that the only way to get a fair crack is to sue.”

Mr. Jones said the National Security Archives has four ongoing lawsuits. Last year, it had one.

Efforts to improve

Congress has attempted tweaks, including the FOIA Improvement Act requiring agencies to publicly post any document requested three or more times. The legislation went into effect in June, so its impact won’t be known until the agencies release their fiscal year 2017 reports in the spring.

But Mr. Llewellyn said agencies appear to be finding ways to circumvent the 2016 law, including denying fee waiver requests or claiming a demand is too vague.

“I think FOIA is trending in the wrong direction,” Mr. Llewellyn said.

The EPA last month announced an initiative to clear its FOIA backlog, which extends all the way to 2008. As of October, the agency had 652 open FOIA requests and claims it will complete 70 percent of those cases by the end of the year.

“These are useful reforms, but they are playing the margins because of the uptick in FOIA requests,” said Margaret Kwoka, a University of Denver law professor, whose research focuses on FOIA.

Ms. Kwoka files about 25 FOIA requests per year but said she rarely succeeds in getting the information. After about a year, she gives up.

The sheer volume of FOIA requests has made it impossible for agencies to keep pace. In fiscal year 2017, the EPA received 11,493 FOIA requests, 995 more than the previous fiscal year, while fighting 36 FOIA lawsuits compared with 12 lawsuits in the previous year.

The 24 agencies received nearly 760,000 FOIA requests last year, but only 725,000 requests — including some held over from previous years — were processed.

The problem, analysts said, is undermanned FOIA staffs at each federal agency. At least 13 agencies have fewer than 100 people working full time to handle hundreds of thousands of documents, and 10 agencies have full-time staffs of no more than 50.

“All the big agencies receive a large volume of FOIA requests, and there is a shortage of people and resources to do this work,” Mr. Stern said. “At the end of the day, someone has to put their hands on each request, search for the records, find the records, review them and determine if anything needs to be withheld. It’s a slow process.”

The nature of the task isn’t easy, either. FOIA officers typically don’t have immediate access to requested files, need to track them down, and then often have to go through the agency’s legal team and even check with other departments before releasing anything.

“It’s easy to bash the government for their poor FOIA performance — and I’ll be the first to admit its terrible — but you have to give them a bit of a break because it is a hard job,” Mr. Steven said. “There are so many bottlenecks in the process, and some are simply unavoidable.”

Fulfilling FOIA demands is costly. All told, the 24 agencies spent nearly $482 million to process claims, including about $35 million to defend denials in court.

Culture of ’let it go’

If agencies want to make a dent in the backlog, the culture needs to change, analysts said.

“The government has performed so poorly across the board for so long that people in the FOIA community expect bad results,” Ms. Kwoka said. “My expectations are quite low that when I heard the State Department had a request pending since 2006, I expected it to be longer. But let’s be honest, that’s truly terrible.”

Rasheeda Clements, a State Department spokeswoman declined to comment for this article.

Limited FOIA funds need to be better allocated, analysts said. In 2015, the Department of Homeland Security became the first agency to launch an app for FOIA requestors. Mr. Jones said that money could have been better spent adding workers to reduce the backlog.

“The allure of throwing technology at the problem won’t fix it,” he said.

• Jeff Mordock can be reached at jmordock@washingtontimes.com.

Please read our comment policy before commenting.