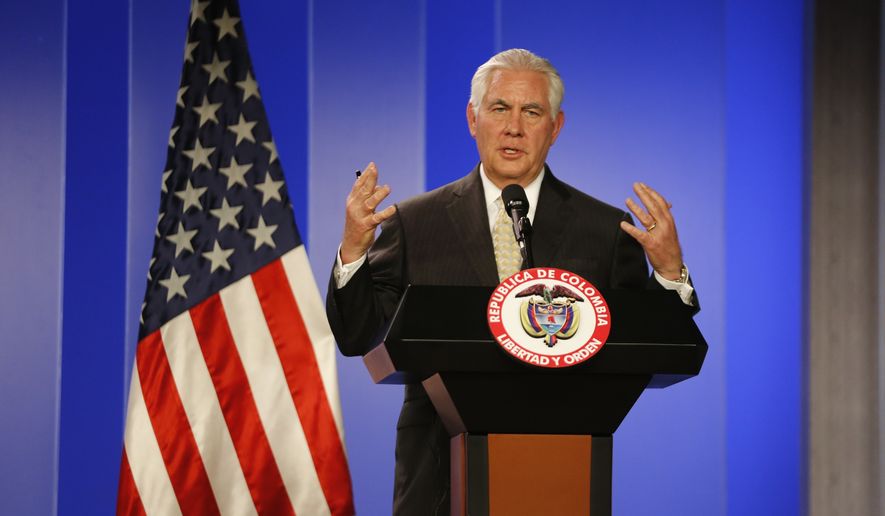

Secretary of State Rex W. Tillerson spent much of his tour of Latin American capitals ratcheting up threats against Venezuela — warning that Washington may move to shut off purchases of the socialist government’s oil and even suggesting that the Trump administration would have no problem with a military coup in Caracas.

A central goal of Mr. Tillerson’s visits to Mexico, Argentina, Peru, Colombia and Jamaica — a tour that ended Wednesday — was to rally the region against the Venezuelan government, which the White House calls a “corrupt dictatorship.”

At his final stop Wednesday in Kingston, Jamaica, Mr. Tillerson confirmed that President Trump was weighing a ban on Venezuelan oil purchases and that the U.S. was working with Mexico and Canada to find alternative sources of oil and gas for Caribbean nations and others dependent on Venezuelan energy.

At least in public, the trip was a success. Despite concerns about Mr. Trump’s trade and security policies when he was elected, Mr. Tillerson had warm receptions at every stop.

It appeared that the era of anti-Washington sentiment that had dominated most of the region may have given way to a thirst for expanded trade and investment with the surging U.S. economy.

But Venezuela, which has pushed a strong anti-U.S. policy as its domestic economic crisis deepens, remains a sore spot. Analysts say the secretary’s of state’s trip added to fears that the Trump administration wants socialist President Nicolas Maduro, the hand-picked successor to the late anti-U.S. populist Hugo Chavez, out of power — even if it means more short-term pain for Venezuelans.

Just before his trip, Mr. Tillerson said in remarks at the University of Texas that the Venezuelan military could manage Mr. Maduro’s “peaceful transition” from power. He also warned of growing Chinese influence and said the Monroe Doctrine is “as relevant today as it was the day it was written.”

Latin American leaders have criticized the 19th-century Washington stand against foreign intervention as a cover for U.S. military intervention.

“Unfortunately, Tillerson’s tour got off to a rough start and may be remembered as an attempt to revive the long-obsolete Monroe Doctrine and the notion that the growing Chinese presence in Latin America is a problem for the United States,” said Michael Shifter, who heads the Inter-American Dialogue think tank in Washington.

“His remarks on both issues at the outset of his trip, along with comments about the military’s possible role in a Venezuelan transition, didn’t help Tillerson achieve his main goal: Build regional support for a more effective, coordinated approach to deal with the Venezuelan crisis,” Mr. Shifter said.

He added that the “tone-deaf” remarks reflect the lack of experienced Latin American hands at Mr. Tillerson’s understaffed department.

The polite receptions Mr. Tillerson received should not be interpreted as unconditional support for U.S. sanctions on Caracas, Mr. Shifter said.

In Mexico City, the secretary’s first stop, Mexican Foreign Minister Luis Videgaray said in no case would his nation “back any option that implies the use of violence, internal or external, to resolve the case of Venezuela.”

That sentiment followed Mr. Tillerson throughout his trip, but it’s unlikely to deter the U.S. administration’s plans for Venezuela.

President Trump has repeatedly denounced the nation’s economic problems, human rights records and political repression. His administration has been building its strategy since February, 2017, when it slapped sanctions on Venezuelan Vice President Tareck El Aissami on charges of playing a major role in international drug trafficking.

The Obama administration sanctioned a handful of Venezuelan officials in response to the Maduro government’s jailing of opposition leaders in 2015.

Mr. Trump escalated the confrontation again in August when he signed broad sanctions to bar international banks from any new financial deals with the Venezuelan government or its state-run oil monopoly, PDVSA.

Venezuela sits atop some of the world’s largest known oil reserves, but Mr. Chavez’s death in 2013 set the nation on an unsteady course.

Critics accuse Mr. Maduro of engaging in an authoritarian-style crackdown on dissent, and a plunge in global oil prices has ravaged the economy and cut into the government’s crucial revenue to fund Chavez-era socialist education, housing and health care programs.

Mr. Maduro has used intimidation and constitutional end-runs to retain his grip on power even in the face of popular protests and major opposition gains in national elections in 2015.

The Trump administration said its goal is to punish the Maduro government’s growing anti-democratic power grab and human rights violations. A White House statement last year said the sanctions are being “calibrated to deny the Maduro dictatorship a critical source of financing to maintain its illegitimate rule, protect the [U.S.] financial system from complicity in Venezuela’s corruption and in the impoverishment of the Venezuelan people, and allow for humanitarian assistance.”

As Mr. Tillerson was wrapping up his trip, officials in Caracas announced that expedited elections would be held April 22, although Mr. Maduro currently is the only candidate on the ballot, The Associated Press reported. The U.S. and European Union have criticized the government’s decision to move up the voting date by several months.

The election date was announced just hours after negotiations broke down between the Maduro government and opposition parties on the logistics of the presidential vote.

Struggling for support

But the administration has struggled to win support from other regional powers, several of which see the measures as more likely to exacerbate Venezuela’s economic crisis.

Mr. Tillerson received only tepid enthusiasm during a joint press conference with Argentine Foreign Minister Jorge Faurie in Buenos Aires when he floated the idea of sharply restricting Venezuelan oil imports to the United States.

Although the Argentine foreign minister said his nation has no tolerance for the “authoritarian deviation” in Caracas, he stopped short of throwing weight behind Mr. Tillerson’s idea.

“It is always our idea that sanctions should not affect the situation of the Venezuelan people,” Mr. Faurie said. “As for the sales of oil and trade in oil that exist, we should … ensure an appropriate balance between what the Venezuelan nation needs and what is being used by the leaders of the Venezuelan government.”

Still, some Latin America analysts remained optimistic. “Latin leaders have traditionally cast a skeptical eye on U.S.-led actions in the hemisphere and have been reluctant to rally behind Washington,” said Eric Farnsworth, vice president of the Council of the Americas, which promotes free markets and democracy in the region. “But it is clear that the situation on the ground [inside Venezuela] is unsustainable, and there is now more of a willingness to countenance stronger actions on a multilateral basis.

“Tillerson’s travel [had] a positive impact in highlighting the growing humanitarian crisis in Venezuela and building a broader consensus for additional regional steps,” Mr. Farnsworth said. “The region should be able to find common ground. Tillerson’s trip [was] an important push in that direction.”

Others argue that the secretary of state and former Exxon Mobil CEO should be more aware of regional sensitivities over U.S. interference — perceptions that undergirded the rise of socialism in Venezuela in the first place.

“If the Trump administration wants to be well-received, it needs to be a little more attuned with what the region thinks of U.S. involvement in countries’ internal affairs,” said Alexander Main, a Latin America analyst at the Center for Economic and Policy Research, a progressive think tank in Washington.

“I think a lot of Latin Americans sense a big double standard with regard to this sort of obsession the U.S. has with regime change in Venezuela under the guise of promoting democracy and human rights,” said Mr. Main. “You have other countries in the region where major human rights violations have occurred and where democracy has been critically undermined while Washington has stayed silent.”

He cited the November vote in Honduras, where U.S.-backed President Juan Orlando Hernandez won a second term in an election that the Organization of American States refused to endorse because of “irregularities.”

“The U.S. supported the election and has really offered no criticism of pretty blatant human rights violations that have occurred there since, including the killing of 30 protesters by state security forces,” said Mr. Main, who argued that skepticism runs high in the region toward the seemingly opposite approach being taken by the Trump administration’s toward Venezuela.

Mr. Main also claimed many in the region of wary of Mr. Tillerson’s history with ExxonMobil.

“Exxon has been at odds with Venezuela for a long time over Caracas’ resistance to allow the company oil exploration rights,” he said. “It’s a factor that really raises some questions in the region, when you now have Tillerson introducing this idea of possible oil sanctions against Venezuela.”

Another close observer of Mr. Tillerson’s trip to the region was far from the scene: China.

Beijing has emerged during recent years as the top buyer of Venezuelan crude. The Trump administration seemed well-aware of that factor last week, when David Malpass, undersecretary of Treasury for international affairs, suddenly accused Beijing of aiding the Maduro government through dubious oil-for-cash investments.

The accusation, made in a speech at the Center for Strategic and International Studies in Washington, prompted swift reaction from China. Chinese Foreign Ministry spokesman Geng Shuang called the accusation “irresponsible.”

Chinese-Venezuelan deals, he said, are in line with international standards and focused not on backing Mr. Maduro but on low-cost housing, electricity generation and other programs for the Venezuelan people.

• Guy Taylor can be reached at gtaylor@washingtontimes.com.

Please read our comment policy before commenting.