MIAMI (AP) - It’s a Wednesday morning, and one by one, the familiar Hurricane faces make their way into the nondescript North Miami warehouse near the corner of Northeast 150th Street and 19th Avenue.

In walks Kenny Kelly, the former University of Miami quarterback and Major League Baseball player. He still looks as lean and fit as he was in 1999, when he led the Big East in passing. The gray whiskers in his goatee are the only clues that he is a 39-year-old father of four.

And, wait, who’s that? It’s Nate “The Great” Brooks, the charismatic Liberty City native who played cornerback for UM from 1994-98, the guy best remembered for scoring a game-winning touchdown off a blocked punt with 29 seconds left to beat West Virginia on the road in 1996. Brooks, who had a brief stint with the New England Patriots, is 42 now. He’s a bit heftier than he was in his playing days - the price, he says, for owning ice cream trucks.

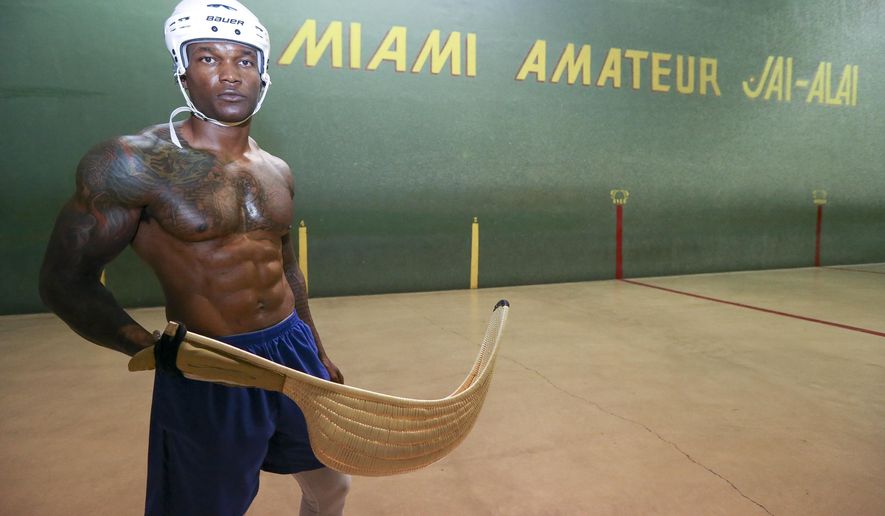

There’s Coconut Grove native Tanard Davis, the former UM and NFL cornerback, 35 now, and in better shape than ever. And former speedy UM and NFL receiver Tony Gaiter, and ex-Canes pitcher Darryl Roque, and ex-hurdler Les Bradley II.

These former Canes have been gathering at the warehouse five days a week since late-January and strapping on helmets. They are on a serious mission: to become professional jai-alai players.

Yes, jai-alai.

Now nearly extinct, jai-alai was once hugely popular up and down the Eastern Seaboard, especially in Miami, where the fronton was known as “the Yankee Stadium of Jai-Alai.” In its heyday, in the 1970s and early ’80s, crowds of thousands showed up to drink, smoke cigars, and see their favorite one-named stars, with long, curved baskets (“cestas”) strapped to their hands, hurling the goatskin ball (“pelota”) against the court walls at speeds up to 170 mph.

It is similar to racquetball, but with high-speed acrobatic catches and throws. And if you’ve never seen it, you will get a chance starting July 1.

Magic City Casino owners are doing away with greyhound racing this summer and reviving jai-alai on a smaller-than-regulation court they are building in the casino’s Stage 305 concert hall.

Rather than import seasoned pros from Spain’s Basque region - increasingly difficult with stricter immigration rules - Magic City CEO Scott Savin and the Havenick family, which owns the casino, came up with the idea of recruiting former athletes from UM, figuring they would catch on quickly and attract new audiences to the dying sport.

An email blast went out last fall to Hurricane alumni of all sports, inviting them to a tryout in early January. Those selected were promised a modest base salary, plus potential bonus money from a $300,000 pot based on their game results. A top player over the five-month season could reach six figures.

Daniel Licciardi, the casino’s Director of Pari-Mutuel Operations, has been involved in jai-alai for four decades. He is overseeing the revival, and the UM athletes are being coached by former legend Juan Ramon Arrasate, known simply as “Arra” in his glory days.

“When I first got the email, I thought it was a prank,” Brooks said. “I was like, ’Is this for real? I can make that much money playing jai-alai?’ I checked it out and found out it was official, so I showed up. I already feel that Hurricane atmosphere, like we’re back in the locker room with that UM swag. I have to get back in tip-top Hurricane shape and put on the greatest show alive.

“I’m gonna tear it up and grab so much of that bonus stack.”

Brooks got his degree in theater from UM, and after football got a business degree from Nova Southeastern. He owns ice cream trucks, sells used cars, has released seven rap albums, and written a self-help book called “Black With No Excuses.” His oldest son, Nate Jr., is a rapper who goes by the name Lil Dred. Another son, Marlin (named after former UM teammate Marlin Barnes, who was murdered), is a cornerback at Ohio University. His youngest, Wayne, got an academic scholarship at FIU.

Brooks said he has dropped 17 pounds and earned a new respect for the sport of jai-alai after two weeks in training.

“This is very hard and challenging,” he said. “This ain’t no playin’ at the park. It’s a professional sport. This is serious. You don’t realize it until you step out there and it’s like, ’Wow, they move faster than me. They can catch and throw better than me.’ You have to respect the sport and people who play it. Word’s going to get out that I’m here, and the whole community is going to come out and bet on me.”

His only complaint: “They already banned one of my moves. It was a backhand move, totally legal in my view. But they don’t want me to come in here and rip the sport up. They want me to do it how they’re doing it; but I’m telling you, I got a backhand move that can really work. They called it The Ambulance Move because they said if I do that, I’m going to hit somebody with the ball.”

Kelly remembers watching jai-alai with his grandfather in Tampa.

“I was very young, but I remember that ball bouncing really fast off the walls, and seeing guys throwing the ball and jumping up on the walls,” Kelly said. “The idea of learning a new sport and competing again after all these years really intrigued me. I couldn’t say no.”

Kelly had been coaching high school football and baseball in the Tampa area, and running a baseball academy on the side. But he missed the thrill of competition. Like Brooks, he says jai-alai is harder than he imagined.

“I compare it to baseball,” Kelly said. “Imagine someone who’s never played baseball before, and now we’re training them to become a professional baseball player in five months. The hardest part is being patient. As bad as you want to do well, some days we come out here and we look bad.

“It’s easier for me, I believe, because I played baseball and baseball is a sport where if you fail 70 percent of the time, you’re an All-Star. So, I had to get used to failing because you fail more than you succeed. Learning jai-alai is the same. We’re going to fail, but we have to be patient. There’s a lot of work to be done.”

When Davis first saw the email, he was reminded of the jingle from jai-alai television ads during his childhood, the one about “The World’s Fastest Game” with the guy jumping off the wall. After bouncing around between six NFL teams and the CFL from 2006 to 2010, Davis had given up on football and become a police officer in Gwinnett County, Georgia.

“I lost my passion to get up every morning and give my heart to something that I felt, at the moment, was not giving me anything in return,” Davis said. “Football was just giving me anxiety, instability from moving around all the time, and not knowing where my check was going to come from.”

Although he enjoyed law enforcement, sports remained his true love. Football had been his ticket out of the streets of Coconut Grove, along with his cousin Frank Gore, an NFL star and Roscoe Parrish. “The streets of Miami gave us three options - drugs, sports, or military,” he said. “I didn’t want to do drugs. I was scared of guns. So, I said, ’I’ll do sports.’ “

Davis, who attended Southridge High, was always among the fastest kids. He ran a 4.27 on NFL Pro Day at UM, and in 2003 he won the 60-meter dash at the Big East Championships, tying Santana Moss’ record. His father, Tim Smith, ran track for the Bahamas and competed against legend Carl Lewis. But he also was “part of the ’80s drug trade, making fast money,” Tanard Davis said. His mother was arrested in 2004 for trafficking heroin and cocaine, and she served time in prison until 2009. Davis helped both parents get back on their feet, and they have turned their lives around.

Davis said he is motivated by his parents’ mistakes and determined to revive his pro sports career in jai-alai.

“The first day out here, I was frustrated,” Davis said. “I felt like, I’m an athlete, I played at UM and in the NFL, I should be able to pick this up. But Arra kept telling me to be patient. I need to train my body to adjust to this sport. My goal is to make a career of it.”

Arra played in the glory days, alongside legend Joey, back in the days when jai-alai stars were recognized on the streets of Miami. He enjoys coaching the former UM athletes, and is keeping expectations low, for now.

“I think it’s a good idea, anything that helps promote the sport,” he said. “I’ve never coached anyone from scratch, but these guys are great athletes, and they’re already throwing and catching the ball much better. I’m not sure what level they’ll achieve in a few months, but I’m confident they’ll be able to compete. It should be fun.”

___

Information from: The Miami Herald, http://www.herald.com

Please read our comment policy before commenting.