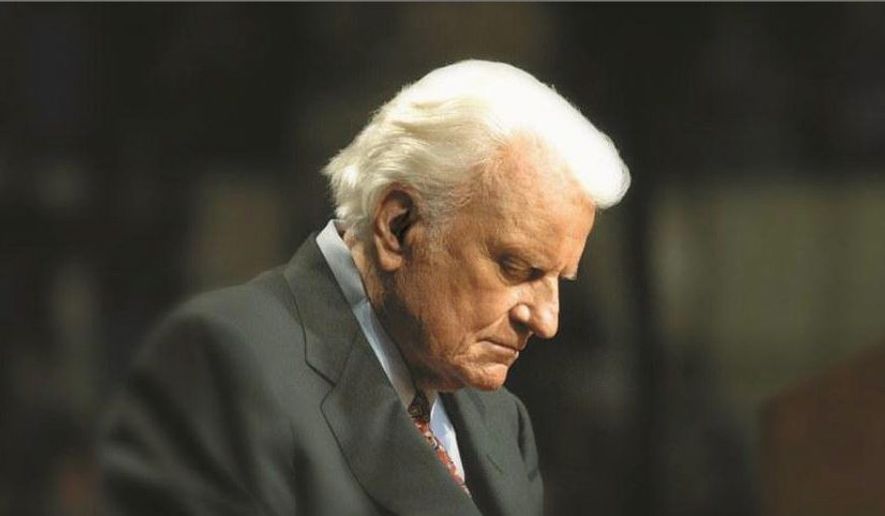

The Rev. Billy Graham, an itinerant Southern tent revivalist who became the foremost evangelist in the world, preaching the Gospel of Jesus Christ to more people than any other man in history, died Wednesday. He was 99.

Mr. Graham, a Southern Baptist, had been in declining health for several years, battling cancer, pneumonia and other ailments. He died at his home in Montreat, North Carolina.

His body will be taken at 11 a.m. Saturday from Asheville, North Carolina, on a several-hour parade to the Billy Graham Library in Charlotte, where he will lie in repose Monday and Tuesday.

The private funeral will be March 2, with the eulogy given by his minister son Franklin Graham. Invitations will be sent to President Trump and America’s former presidents, according to publicist Mark DeMoss.

Mr. Trump tweeted Wednesday morning: “The GREAT Billy Graham is dead. There was nobody like him! He will be missed by Christians and all religions. A very special man.”

“Billy Graham’s ministry for the gospel of Jesus Christ and his matchless voice changed the lives of millions,” Vice President Mike Pence tweeted. “We mourn his passing but I know with absolute certainty that today he heard those words, ’well done good and faithful servant.”’

PHOTOS: Celebrity deaths in 2018: The famous faces we've lost

Former President George W. Bush issued a statement: “Billy Graham was a consequential leader. He had a powerful, captivating presence and a keen mind. He was full of kindness and grace. His love for Christ and his gentle soul helped open hearts to the Word, including mine. Laura and I are thankful for the life of Billy Graham, and we send our heartfelt condolences to the Graham family.”

“Billy Graham was America’s pastor,” said former President George H.W. Bush. “His faith in Christ and his totally honest evangelical spirit inspired people across the country and around the world. I think Billy touched the hearts of not only Christians, but people of all faiths, because he was such a good man. I was privileged to have him as a personal friend. … He was a mentor to several of my children, including the former president of the United States. We will miss our good friend forever.”

Mr. Graham’s early flamboyance, when William Randolph Hearst and his newspapers propelled him onto the scene as “God’s Gabriel in gabardine” — gabardine often in lime green set off by purple shirts and bright-red neckties — eventually gave way to Savile Row tailoring and magisterial authority as he became the confidante of presidents and chaplain to the nation, praying at inaugurals, offering spiritual consolation on the occasions of great tragedies and presiding at state funerals.

But he never lost his enthusiasm for the revivalist’s message of repentance of sin and redemption through the sacrifice of Christ on the cross, invariably preaching from his favorite Bible verse, John 3:16: “For God so loved the world that He gave His only begotten Son, that whosoever believeth in Him shall not perish, but have everlasting life.”

When others called his work “mass evangelism,” he invariably corrected it to “personal evangelism on a grand scale.”

In his early crusades — he dropped the word “crusade” for a time in deference to Muslim sensitivities after the Islamist attacks of Sept. 11, 2001, but restored it for his last crusade in New York City in June 2005 — he was often mocked for his boyish enthusiasm and the evangelist’s message, delivered “with the bark on,” but one by one the critics who arrived to scoff at crusades in New York, London, Hong Kong and other venues far from his North Carolina origins went away in admiration.

PHOTOS: Evangelist Billy Graham, who reached millions, dies at 99

Former President Barack Obama said Wednesday, “Billy Graham was a humble servant who prayed for so many — and who, with wisdom and grace, gave hope and guidance to generations of Americans.”

“Rosalynn and I are deeply saddened to learn of the death of The Reverend Billy Graham,” former President Jimmy Carter said in a statement. “Tirelessly spreading a message of fellowship and hope, he shaped the spiritual lives of tens of millions of people worldwide. Broad-minded, forgiving, and humble in his treatment of others, he exemplified the life of Jesus Christ by constantly reaching out for opportunities to serve.”

Former President Bill Clinton said in a statement: “I will never forget the first time I saw him, 60 years ago in Little Rock, during the school integration struggle. He filled a football stadium with a fully integrated audience, reminding them that we all come before God as equals, both in our imperfection and our absolute claim to amazing grace. … Billy has finished his long good race, leaving our world a better place and claiming his place in glory.”

Graham admirers called his singular rise the work of the Lord, but it also was made on a Jacob’s ladder with rungs carved by newspaper publishers, presidents, prime ministers and occasional curious royalty, and above all by his own unchallenged ethical character.

He followed in the path of famous evangelists before him, notably Billy Sunday, to whom he was often compared in his early years, and the likes of Dwight L. Moody, Fuller Torrey, Gipsy Smith and others.

“His greatest final legacy may be the tens of thousands of other itinerant evangelists, and many of them from the Third World, who he has trained,” said William Martin, Mr. Graham’s biographer.

Besides Franklin Graham, he is survived by sister Jean Ford; daughters Gigi, Anne and Ruth; son Ned; 19 grandchildren; and numerous great-grandchildren. His wife of nearly 64 years, Ruth, died in 2007.

Crusading evangelist

As pastor, preacher, author and finally world statesman, Mr. Graham always returned to the call of delivering his message that in Christ alone can man find peace with God. He promoted ecumenical cooperation among evangelical churchmen for whom ecumenism had never held much appeal, but he made certain theological points clear in each of his thousands of sermons.

“Whereas a pastor can use a shotgun and cover the whole range of Christian doctrine, an evangelist shoots with a rifle,” he said in a 1986 interview with The Washington Times, on the occasion of his third revival, or crusade, in the nation’s capital.

The evangelist’s “rifle shot” of Scripture and the call to repentance was heard around the world by an estimated 1 billion persons in the spring of 1995, when a satellite-boosted Puerto Rico crusade, “Global Mission,” extended over several weeks in 117 languages.

In 1992 he cracked open a final redoubt of communism, preaching a simple Gospel message to a carefully screened congregation in North Korea’s only chapels, one Roman Catholic and one Protestant, in Pyongyang. Hard-eyed government officials sat mesmerized by his 25-minute call to repentence and salvation through the atoning sacrifice of Jesus Christ, again based on John 3:16, and several Communist commissars, who listened with rapt attention, went away with troubled expressions on their faces, asking earnest questions of several American visitors in the audience. Asked one Korean official of a visiting American editor of The Washington Times: “This story about Jesus — have you ever heard of it?”

He had earlier held crusades in Moscow, during the waning years of the Cold War, and drew enormous crowds. But he did not realize his dream of holding a crusade in China.

Mr. Graham drew his largest one-day American audience in 1991, attracting a crowd of 250,000 in New York’s Central Park; he drew 1.1 million persons to a single service in Seoul in 1984. But associates held out hopes that a China crusade would break all one-day records.

Mr. Graham was born in 1918 into a Reformed Presbyterian family, the descendants of Scots settlers who arrived before the American Revolution, and he described his early years as a continuous search for girls and good times. He yearned to become a major-league baseball player and showed skill and promise in amateur games on the sandlots of North Carolina, then a hotbed of professional baseball, where every mill town had a team.

At 16, at a tent revival conducted by a well-known Southern revivalist named Mordecai Ham, he “hit the sawdust trail to make a decision for Christ.” He studied at Bob Jones University, a strict fundamentalist school in nearby Greenville, South Carolina, and then attended a Bible institute in Florida, and in 1938, when he was 18, he surrendered to “the call” to enter the ministry. His fiery preaching, his colorful clothes and his cadenced Carolina idiom quickly earned him the sobriquet of “the preaching windmill.”

Years later, pedometers attached to his legs revealed that he walked the equivalent of 40 miles in a month of preaching, as he paced the stage illustrating his points with gestures and dramatizations of Christ’s love and deliverance, of God’s wrath to come for the unrepentant sinner. At the end of his sermon, with an invitation to sinners to accept Christ to the strains of the old revivalist hymn “Just As I Am,” he was typically exhausted, his voice hoarse, his clothes drenched in perspiration.

Nevertheless, despite the expenditure of what appeared to be boundless energy, he was plagued throughout his life with delicate health, especially respiratory ailments. His great lionine head, crowned with a thatch of dark blond hair, and flashing blue eyes bespoke an Adonis-like figure. But his 6-foot 2-inch frame was frail and lean.

He left the Presbyterian denomination of his family in 1939, when he was baptized and ordained in a Southern Baptist church. At his death he held his membership in the First Baptist Church of Dallas. He entered Wheaton College, an independent evangelical institution in Wheaton, Ill. There he met Ruth McCue Bell, the daughter of a Presbyterian medical missionary to China. When Mr. Graham visited Pyongyang in 1992 he made a point of visiting the schoolhouse, now a government office building, where his wife had attended classes as a schoolgirl before the outbreak of World War II. They were married in 1943 and she was often credited with broadening the young Carolinian’s world view, of redirecting his talents and smoothing rough-hewn edges.

With a degree in anthropology from Wheaton, he was called to be the pastor of the First Baptist Church in Western Springs, Ill., and soon afterward started his first radio program, “Songs in the Night,” broadcast from Chicago. There he met George Beverly Shea, who directed the music for his years of evangelistic crusades.

’The Canvas Cathedral’

From 1944, Mr. Graham became the first traveling organizer for Youth for Christ, an organization devoted to evangelizing college campuses, and in one year United Airlines gave him an award for being the airline’s best customer. His first book, “Calling Youth to Christ,” was published in 1947.

Lightning struck in Los Angeles in 1949. He was conducting a revival in a tent he had erected on a vacant lot near downtown Los Angeles, drawing respectable but not huge crowds to what his newspaper ads called “the Canvas Cathedral.” One night William Randolph Hearst, curious, told his driver to stop his limousine to enable him to listen from the edge of the crowd. He was fascinated by the spectacle of the fervent evangelist, prowling the platform like an athlete. Mr. Hearst, whose newspapers then comprised the nation’s most influential newspaper chain, sent out a teletype message the next day to all editors: “Puff Graham.”

Television was in its infancy, and every town and city had a newspaper and the major cities had several. Hearst’s “puffery” soon attracted the attention of Life magazine, which then exercised a readership impact equivalent to the combined power of all the television networks today, and he was put on its cover. Other newspapers, including the New York Times, which in those days strongly influenced what other newspapers thought important, soon followed.

He burst on to the international scene with his crusade in London’s Haringay Arena in 1952. The simple message of John 3:16 appealed to millions disillusioned by the ravages of World War II, and the crusade ran for months instead of the planned weeks, attracting royalty and celebrities among the hundreds of thousands who sat entranced by the young American. Famous newspaper columnists who went to sneer wrote admiring columns, some suggesting that they, too, had fallen under the power of the Gospel. The London crusade, as it turned out, was crucial to making the evangelist an international figure.

Soon Mr. Graham could enforce a requisite for a citywide crusade: Every major church must participate, the offerings collected would be audited by an independent accounting firm, and expenses paid by a responsible local group, and any proceeds would go to the non-profit Billy Graham Evangelistic Association to pay for other evangelism. Mr. Graham was paid a salary by the association.

At the conclusion of his sermons, counselors waiting to receive penitents at the “altar call” would direct them to a local church. The sponsors of the crusades organized an extensive follow-up ministry to offer further counseling to the new Christians. His fervent evangelism, though a familiar part of the culture of the South, was new to much of the nation and over time his greatest success was in the cities of the North.

Mr. Graham first put his sermons on radio in 1950 with “The Hour of Decision.” He later tried a weekly television program, but gave that up for a pattern in use at his death — telecasting about three crusades a year in prime time.

He insisted on desegregating the seating in his revivals as early as 1953 in Memphis, when this was a radical departure from custom in the South, and had an inter-racial staff by 1957. He aroused fierce protests when he insisted on open seating at a crusade in Little Rock when Arkansas and the Deep South were aflame in the wake of the desegregation at the point of U.S. Army bayonets of Little Rock’s Central High School.

“On race, he’s been largely misunderstood,” his biographer says. “He was way ahead of his own group.”

He was embarrassed in 2002 with the release of certain Nixon tapes, in which he was heard making slighting remarks about Jews. He apologized on release of the tapes, saying the remarks did not represent his feelings. In fact, Mr. Graham had cordial relations with American Jews, and was particularly supportive of Israel.

During his first crusade in the nation’s capital in 1952, President Harry Truman, a fellow Southern Baptist, invited him to the White House, but never invited him back. His biographer calls it his first “political snub.”

Later, Mr. Graham wrote to Dwight Eisenhower in Europe, urging him to run for president. He traveled to visit the war hero in Paris. Consequently, Mr. Graham prayed at the Eisenhower inauguration and later baptized Mr. Eisenhower, who would become a Presbyterian, as a symbol of his faith.

Though he later developed a friendship with Richard Nixon, Mr. Graham spent more nights at the White House as the guest of Lyndon Johnson than as a Nixon guest. He was a White House guest of both Jimmy Carter and Ronald Reagan, and grew particularly close to both George H.W. Bush and George W. Bush. But he, like many Southerners with Republican sympathies, remained a registered Democrat.

Presidents and politics

An all-summer crusade in 1957 in New York City finally built a bridge between the evangelist and mainstream liberal Protestants. That prompted the Rev. Bob Jones, then an influential fundamentalist, to say: “Billy Graham was doing more to harm the cause of Christ than any other living man.”

He also founded, with his father in law, what would become the nation’s largest religion magazine, Christianity Today. Two decades later, in what one magazine declared the “Year of the Evangelical,” born-again candidate Jimmy Carter became president and the new “religious right” was soon to enter politics. But by then, Mr. Graham had dramatically withdrawn from political associations, especially after being close to President Nixon when he fell in the Watergate scandal.

“There’s probably the most residual disappointment with Billy Graham over his uncritical approval of Mr. Nixon, and some of that over Lyndon Johnson,” his biographer says of the prevailing media opinion.

When Mr. Graham read Mr. Martin’s finished manuscript for, “A Prophet with Honor,” he first saw documentary accounts of how Nixon operatives had strategically used the evangelist for one political need or another. “He told me then he felt like he’d been a sheep led to slaughter,” Mr. Martin recalled.

When Gerald Ford asked to speak at a Graham crusade during his 1976 race for re-election against Mr. Carter, the evangelist said no, not unless both candidates appeared together.

“In the early 1980s he was advising people like Jerry Falwell and the others to not get too tangled in politics,” Mr. Martin said. “They didn’t listen, though.”

Mr. Graham returned to the White House for inaugurals, which he regarded as state occasions, not political appearances. He gave foreign travel briefings to Ronald Reagan and was with George Bush the night before Operation Desert Storm was unleashed in the Persian Gulf. The Bush family often turned to him for spiritual guidance.

But he revealed a certain naivete, if not innocence, when he ventured close to presidential politics. After praying at President Clinton’s inaugural, he remarked that the onetime Arkansas Sunday-school boy, who as governor sang in the choir of his church, “would make a very good Baptist preacher.” When his remarks sympathetic to Mr. Clinton, on the eve of his impeachment, were interpreted as rationalizing his behavior with Monica Lewinsky, Mr. Graham quickly clarified his remarks in an op-ed essay in The New York Times. Nevertheless, at his last crusade in New York City, he joked — or many thought he was joking — that Mr. Clinton should become an evangelist “and let Hillary run the country.”

What seemed to please Mr. Graham most in his late years was to train thousands of his young men from around the world, and to preach in foreign capitals. In 1986, he envisioned a way to make his reach global, all at once. He had preached in Africa as early as 1960, but in recent years the “Global Mission” project used crusades in England, Germany, Argentina and Hong Kong to project his message by satellite to surrounding continents.

⦁ Sally Persons, Mark A. Kellner and Larry Witham contributed to this report.

• THE WASHINGTON TIMES can be reached at 125932@example.com.

Please read our comment policy before commenting.