OPINION:

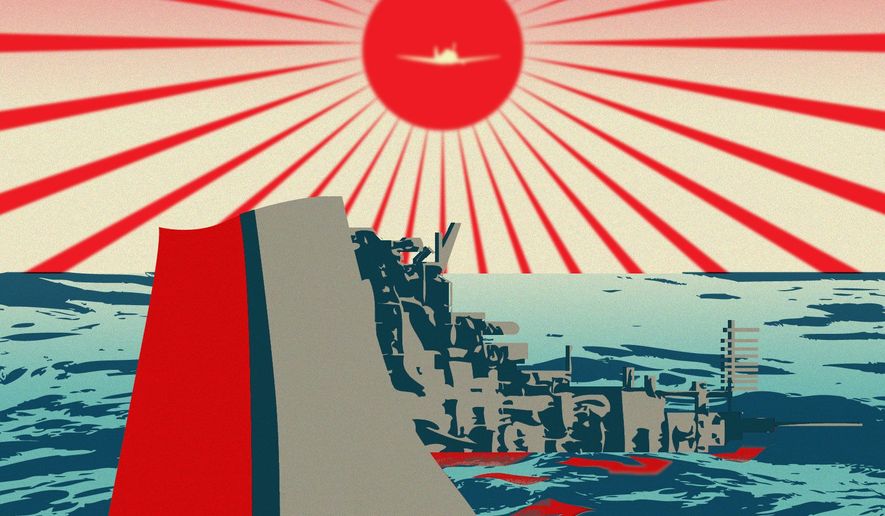

On a lazy, sunny Sunday morning Dec. 7, 1941 at 7:48 Hawaiian time, a bitterly divided America was suddenly shocked into a singleness of purpose it had never seen before.

Three-hundred-fifty-three Imperial Japanese aircraft in two waves, launched from six aircraft carriers, attacked our naval base at Pearl Harbor. Of eight battleships — the Arizona, Oklahoma, West Virginia, California, Nevada, Pennsylvania, Tennessee and the Maryland — four were sunk and the others severely damaged. Also severely damaged were three cruisers, three destroyers and several auxiliary ships. 188 American aircraft were destroyed, 2,403 Americans were killed and over 1,100 wounded.

Japanese losses were light. Having succeeded beyond all expectation, and fearing a counterattack, the Japanese canceled a planned third wave. They would later regret this decision. Fortunately, our carriers were away on maneuvers, as they would replace the battleships as the queen of naval warfare and our subsequent victories at sea.

At Pearl Harbor, on “a date which will live in infamy” as President Franklin Roosevelt so eloquently described it, occurred one of the greatest and most consequential events of world history.

Yorktown, Gettysburg, Pearl Harbor, Midway and D-Day are names written indelibly in our national memory. They each were historical plot points that spun the cataclysmic current of action into a very different and decisive direction.

During the early days of December 1941, the tide of World War II was turned. On Dec. 5 and 6 the Soviet Union counterattacked the Germans at the gates of Moscow and on Dec. 7 the Japanese attacked Pearl Harbor. The next day the United States declared war on Japan, and on Dec. 11, Hitler, honoring his alliance with Japan, declared war on the United States. We promptly reciprocated.

So, within the dizzying rapidity of a few short days the fatal issue of total war was joined, and the future of the Axis was sealed by its own folly and folded away into history’s fateful envelope. Its verdict would soon reveal the abject defeat, destruction and devastation of the Fascist plot against humanity.

Hitler could win a European war and Japan could win an Asian one, and each had essentially done so, but even the melding of these two malignant war machines could not win a world war against the Grand Alliance of the United States, the Soviet Union and the British Empire.

The Japanese soon realized that their celebratory success was Pyrrhic, and, ironically, it was they who said it best as Adm. Isoroku Yamamoto, commander of all Japanese naval forces, is reported to have lamented, “I fear we have awakened a sleeping giant and filled him with a terrible resolve.” Adm. Hara Tadaichi later echoed him saying, “We won a great tactical victory at Pearl Harbor and thereby lost the war.”

Winston Churchill, upon hearing the news of Pearl Harbor said, “Being saturated and satiated with emotion and sensation, I went to bed and slept the sleep of the saved and the thankful.” He knew there “was no more doubt about the end.”

Providence sometimes “writes straight with crooked lines,” and our inherent national cohesion arising from the catastrophe of Pearl Harbor became the elixir of success in that greatest of all struggles. The Japanese had inadvertently performed a kind of emotional alchemy upon the American psyche as we decided that since strength came from unity, and we had to be strong, we had to be one. Indeed, through that realization our people converted a time of extreme toil and tears into total triumph over a criminal aggression of unparalleled malevolence.

Earlier, Abraham Lincoln both admired and admonished America in proclaiming that all the armies of the world “could not by force, take a drink in the Ohio, or make a track in the Blue Ridge, in a trial of a thousand years” if our country is united. Or, in his inversion of E pluribus unum, he added a much sterner warning, that “a house divided cannot stand.”

In his first Inaugural Address he hoped to pre-empt our near fatal schism with the unique poetic power of his words and voice in pleading for national unity and peace:

“Though passion may have strained, it must not break our bonds of affection. The mystic chords of memory, stretching from every battlefield, and patriot grave, to every living heart and hearthstone, all over this broad land, will yet swell the chorus of the Union, when again touched, as surely they will be, by the better angels of our nature.”

We were never as united as after Pearl Harbor, but today we seem almost as divided as when Lincoln appealed to our people in those immortal words of precaution and praise.

To be sure, we have formidable, indeed perilous, problems before us. They do not need enumeration. Divided we will not defeat them, they will defeat us, but unified we can succeed yet again as we have always done before. With America it is never a question of capacity but of will — nothing more is needed — anything less will fail.

Pearl Harbor demonstrated this beyond all doubt. So, let this great lesson be what we learn from its remembrance. We need the unity of a common purpose, and not the disunity born of calumny and curses, insults and invective. To employ our liberties as an instrument of tribal intolerance is to drink poison from a golden cup. America is an idea, a sublime but fragile dream enumerated in our Declaration of Independence, nothing more can ever be done and nothing less will ever do. As great as it is, America must hold fast to this the grandest of dreams or it will descend into the nightmare of dissolution, despair and a defeat greater than any enemy could ever impose.

• Phillip H. McMath, a trial lawyer in Little Rock and Vietnam veteran, is the author most recently of “The Broken Vase.”

Please read our comment policy before commenting.