OPINION:

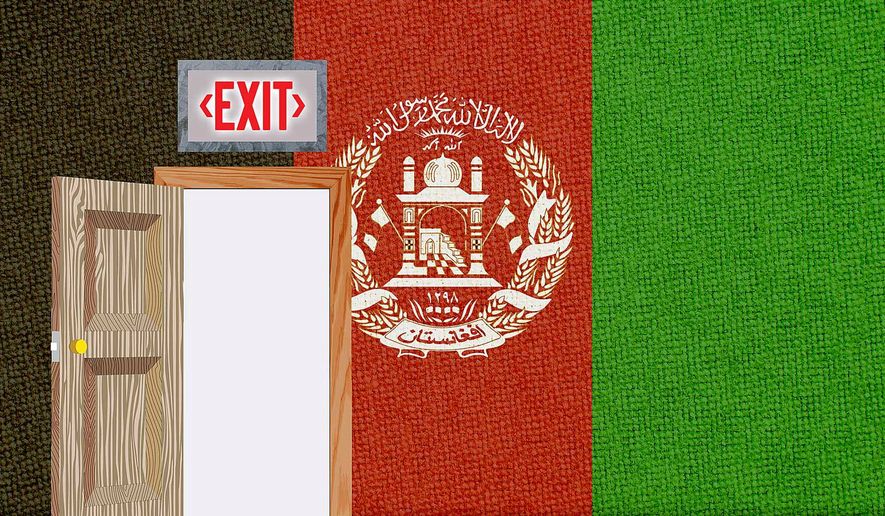

Getting into Afghanistan is easy; getting out with your head and body attached to each other is another matter. Three U.S. presidents have wrestled with that problem. However, none has been able to successfully define what a satisfactory end state in Afghanistan should look like.

The closest we have come so far is to leave with an Afghan government that can survive without the presence of U.S. troops. That is not going to happen if the Kabul government continues to try to micromanage the entire country. Afghanistan has been a mess for centuries, and it will not be a strong, centrally controlled nation-state for decades if ever, and it is not our job to change that.

The protagonist of the classic novel “The Far Pavilions” observes that Afghanistan is the biblical Land of Nod, where God exiled Cain after he killed his brother Abel. He notes that — as descendants of Cain — the Afghans are violent and personally ungovernable. Interestingly, that is basically the same way the narrator of John Steinbeck’s “East of Eden” describes Americans. At least half of American citizens have resisted strong central government for two-and-a-half centuries. It is therefore amazing that — for 18 years — American decision-makers have expected better of the Afghans.

Since the Mongol invasions ended, Afghanistan has only known a strong working central government from 1880 to 1901, when Abdur Rahman Khan — known as the Iron Emir — imposed centralized rule on the nation from Kabul. But he did so in a manner that would make him an international pariah today. A military despot, the emir used brutal suppression of tribal revolts by enslavement and massacre, invasive spying by secret police, and ethnic cleansing to keep the nation unified. Ironically, however, some of his methods of rule helped to ensure that none of his successors would be able to exercise strong central rule.

Abdur Rahman forbade the building of telegraphs, railroads and national roads in order to deny the British and Russians easy means to invade or spread their influence in Afghanistan. However, this lack of infrastructure has made it impossible for his successors — including the present Kabul government — to easily extend its control by providing goods and services to the remote regions that make up the bulk of the nation’s geography. Abdur Rahman also consented to the Durand Line, which designated the boundary between Afghanistan and what is now Pakistan. Although it ensured peace with the British, it arbitrarily placed many Afghan Pashtun’s in another country and gave rebellious Pashtuns — including the Taliban — a convenient sanctuary.

As a result of all of this, there are really two distinct Afghanistans today. The first is the relatively liberal urbane population of the five major cities and those areas that can be reached by the limited road network. The second lies in the population of remote valleys and mountain strongholds that are hard for the government to reach. Most of those areas are firmly mired in the 14th century and they are content with that. Many — if not most — are happy with Sharia law, and distrust judges and administrators sent from Kabul who are often corrupt and don’t understand local customs and mores. Many of these areas are heavily Pashtun and represent the core of recruits for the Taliban. Most of these are not religious fanatics, but they see the Taliban as protecting the ancient tribal values of Pashtunwali (the way of the Pashtun) and the security forces of the government as foreign puppets.

The Taliban won’t overrun the urban areas, and the government cannot destroy the Taliban in the rural Pashtun heartland no matter how much help it gets from us. Foreigners can’t break this stalemate, nor should we continue to try.

If the Trump administration wants to get out of Afghanistan short of cutting and running, it should base its negotiating strategy on two things. First, it should convince the Kabul government to allow self-government by election in the provinces. The urban areas will not vote in Taliban candidates and the Taliban would be forced to live up to their claim of providing better local governance than Kabul, and they won’t be able to do so in the long run. Second, the withdrawal of U.S. and Western forces should be contingent on a Taliban promise to keep foreign jihadists out of the districts where they govern. If the foreigners return, so will the Americans.

Only the Afghans can eventually change the Land of Nod. We should stop trying.

• Gary Anderson is a retired Marine Corps colonel who has served as a civilian adviser and instructor in Afghanistan. He lectures on Alternative Analysis at the George Washington University’s Elliott School for International Affairs.

Please read our comment policy before commenting.