OPINION:

One of the nicer features of the Trump presidency is that very nearly every Trump-related media meltdown — all-consuming, overstated, ubiquitous — over a Twitter misspelling, or TV interview, or awkward photograph at a NATO summit, is quickly subsumed by another crisis/meltdown. The end of the world, as it were, is continually being postponed as the meteor hurtling toward Earth changes course.

I was reminded of this recently when Secretary of Defense James Mattis announced his impending retirement in a letter to President Trump which made it clear that he was resigning in protest. I applaud Gen. Mattis for his dramatic gesture: One of the less attractive features of the American system is that cabinet secretaries, and other senior officials in any administration, so seldom quit on principle and, instead, hang on for the sake of a deceptive “stability” or, worse, because they savor the perquisites of office.

By contrast, Mr. Mattis made it clear that he did not approve of Mr. Trump’s decision to withdraw U.S. troops from Syria and added, in language suitable for the occasion, that the president deserves a secretary in greater harmony with Mr. Trump’s policies.

As might be expected, Mr. Mattis’ resignation and implied rebuke were widely reported and swiftly interpreted — for the requisite week or so — as a cataclysm unprecedented in American history. To be sure, such assertions are now commonplace in the Trump era, reflecting the widespread disdain for the president in numerous circles and — a chronic problem of modern journalism — startling ignorance about American history.

They are also representative of the media consensus about Mr. Mattis: The plain-spoken scholar-Marine has been regarded as the “adult in the room” of the Trump funhouse, a soothing presence for uneasy allies and the rare expert to whom Mr. Trump would defer.

But I am not so sure if this particular meltdown was entirely justified, or that the general’s exit is necessarily a bad thing. To begin with, like most general officers, and contrary to media stereotype, Mr. Mattis has tended to be a cautionary influence in the design and execution of Mr. Trump’s policies and, above all, a steadfast guardian of the status quo.

He has also tended to administer the Department of Defense as if it were a strictly military institution: He has surrounded himself with (no doubt equally impressive and accomplished) career officers and has been comparatively opaque in his relations with Congress and the press — and by extension, the American public.

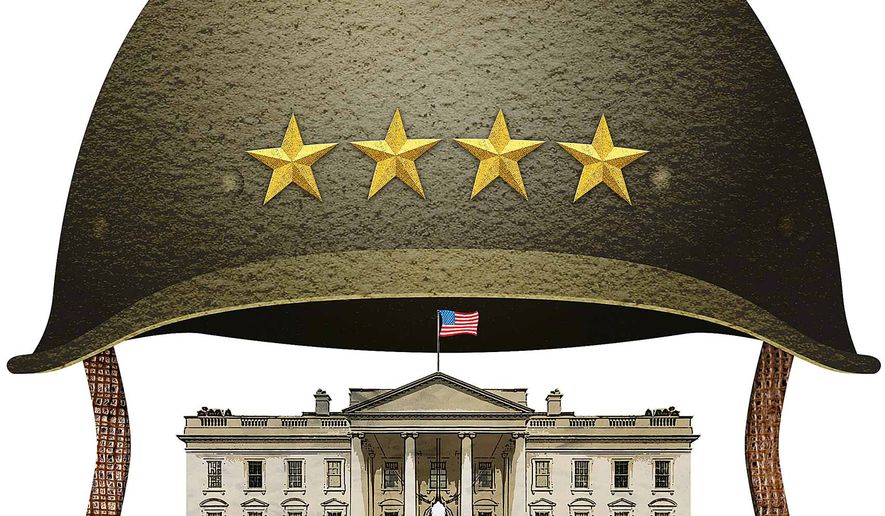

This is neither a surprise nor, in many respects, a defect: Part of Mr. Mattis’ appeal, both to Mr. Trump and an admiring press corps, is that he is not a politician but a professional warrior who has devoted himself to the service of his country and knows his duty. However, the Pentagon itself is not a military command but a department of government, charged not only with the national defense but with the administration of national policies that are set, in our constitutional system, by civilian institutions — the presidency, Congress — accountable to voters.

There is nothing wrong, in principle, with a secretary of Defense lately in uniform: Gen. George C. Marshall (1950-51) was Mr. Mattis’ distinguished predecessor in that respect. But there is a reason why, when the armed forces were unified and the Defense Department was created (1947), statutory obstacles were placed in the path of generals and admirals as secretaries. Marshall, after all, was recalled to service when his civilian predecessor botched the initial stages of the Korean War, and Marshall returned to retirement as quickly as possible.

Or put another way: A charismatic Marine with a well-furnished mind and gift for inspiring the troops may not be the best choice to think creatively about policy or question precedent.

Which is why, with the impending departures of Mr. Mattis and the White House chief of staff, Gen. John Kelly, Mr. Trump has a chance to reconsider his penchant for military men in positions designed not for command efficiency or devotion to mission but someone with democratic instincts and political talent — in short, a civilian.

One of the interesting, and at times admirable, things about Donald Trump is that he tends to regard the challenges of the presidency not with caution or reverence for precedent — or desire to please — but as a series of questions for which the right answers are not always correct. There is no good reason, after all, why old policies which appear to have failed must be pursued ad infinitum, or that habits of governance or policy presumptions that made sense decades ago remain valid indefinitely.

This is not to say that Mr. Trump’s disruptive instincts are always right: Certain alliances, principles and habits of mind endure because they have been, and remain, successful. But not always — and Mr. Trump’s willingness to shatter the crockery has been refreshing at times, as well as unnerving. I suspect that Gen. Mattis, to his credit, understands all this and is looking forward to some well-earned rest and recreation.

• Philip Terzian, former writer and editor at The Weekly Standard, is the author of “Architects of Power: Roosevelt, Eisenhower, and the American Century.”

Please read our comment policy before commenting.