OPINION:

President Trump’s decision to freeze current U.S. tariffs on imports from China for 90 days and forestall threatened new levies mainly in return for Chinese promises to buy more American goods adds voluminously to the questions already raised as to whether his China trade policy is seeking coherent, feasible goals that will ultimately leave America better off.

Not that all such questions and doubts until now have been incredibly swift. For example, the president’s moves so far have also exposed the fatuousness of claims that China-centered global supply chains are set in stone (the actual and threatened tariffs are already triggering production and job flight from China — though rarely to the United States); and that the trade curbs would decimate American producers and job creators who relied on Chinese inputs of various kinds (no damage has turned up in U.S. economic data yet).

More serious, and still left open, are uncertainties over whether administration demands for fairer Chinese treatment of U.S.-based businesses operating in China won’t simply encourage the building in China of more export-focused production that balloons the American trade deficit; and whether the president’s (warranted) determination to shrink the bilateral trade deficit won’t blind him to the greater importance of this imbalance’s makeup — producing deals that encourage China to turn out more high-value products, like advanced manufacturers, and the United States to produce more low-value goods, like raw materials.

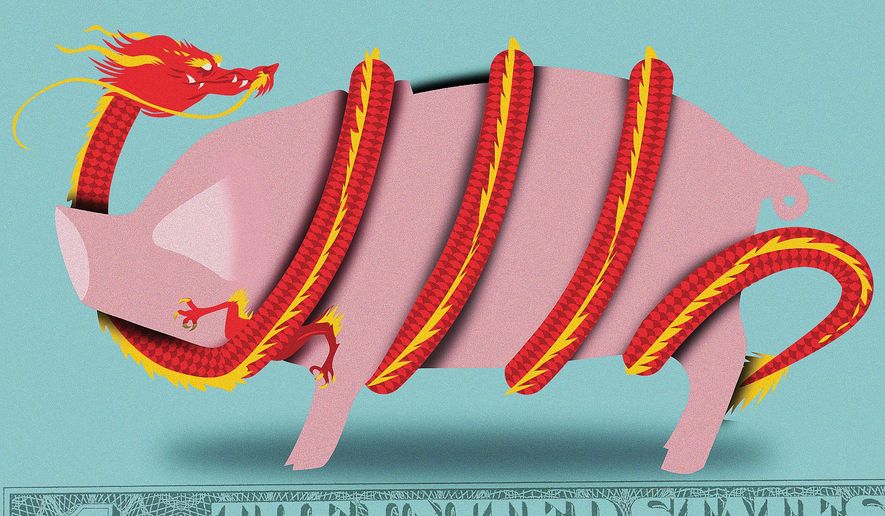

But remaining most important and least clear of all: How can even complete Chinese agreement to America’s central demands — to halt the strategy embodied in the Made in China 2025 program to achieve global technological supremacy largely via the outright theft or extortion of intellectual property — be adequately verified?

Of course, the new U.S. tariff freeze has by no means secured a Chinese commitment to end or even significantly scale back the Made in China 2025 blueprint. According to the White House, Beijing has simply agreed to “immediately begin negotiations on structural changes with respect to forced technology transfer, intellectual property protection, non-tariff barriers, cyber intrusions and cyber theft, services and agriculture” and to “endeavor to have this transaction completed within the next 90 days.” If no deal is reached, the 10 percent tariffs already in place on $200 billion worth of Chinese goods since September will rise to 25 percent.

As Bloomberg news reported, however, China’s official description of the truce’s terms simply states that the two countries “will work together to reach a consensus on trade issues,” and makes no mention of the 90-day deadline. The same uncertainty surrounds the President’s tweeted claim Sunday night that Beijing “has agreed to reduce and remove tariffs on cars coming into China from the U.S.”

Yet even if China announced the immediate termination of Made in China 2025, the United States would be utterly incapable of measuring compliance adequately. After all, ever since they’ve been doing business in China, American businesses have been loathe to complain publicly about losing their most valuable trade and commercial secrets hand over foot. The prospect of being punished and shut out of the Chinese market has been more than enough to cow them, and absent such complaints, Washington would be hard-pressed to identify violated commitments.

In addition, the Chinese government is so secretive that American officials would face even greater difficulties documenting instances of Beijing illegally subsidizing Chinese entities that compete with U.S. counterparts anywhere around the world, or credibly accusing China of discriminating against American businesses in bids for government contracts.

The resulting dilemma leaves the United States with only one acceptable alternative: Starting to disengage economically from China as soon and as completely as possible. Existing tariffs should be expanded and raised high enough to encourage the further movement out of China of factories supplying the United States, and to discourage U.S. companies from establishing or expanding their presences in China. (Even migration to third countries would achieve the key American aim of weakening the Chinese economy, and much remaining Chinese production would find selling to the United States at the expense of domestic American firms prohibitively expensive.)

Washington should ban outright further high-tech investments in China, in order to end the Chinese military’s access to this know-how. And Chinese direct investment in the U.S. economy should be prohibited as well — both to prevent strategically important assets from being acquired, and because a larger footprint in the United States by Beijing-controlled entities can only distort and therefore undermine free market competition.

America’s decision to expand commerce with China and integrate the two economies more tightly assumed that closer ties would move China in more capitalistic, more democratic, and more peaceful directions. Decades later, the abject — and increasingly dangerous — failure of this experiment could not be more obvious. Even though successful disengagement is no likelier to be pain-free as Mr. Trump promised in connection with his current trade war, the nation’s security and prosperity demand no less, and it’s high time for this president to exercise some genuine leadership and explain to the public exactly why.

• Alan Tonelson, founder of RealityChek, a public policy blog focusing on economics and national security, is also the author of “The Race to the Bottom” (Westview Press, 2002).

Please read our comment policy before commenting.