Police in St. Louis pulled over two suspected heroin dealers moving the drug in a rental car.

A bag ripped open during the stop, spilling fentanyl all over the car’s trunk. Smaller than a grain of sand, fentanyl is a synthetic opioid so lethal even trace amounts can kill.

The rental car company called Laura Spaulding-Koppel, CEO of crime scene cleanup company Spaulding Decon, to remove the toxic substance. Ms. Spaulding-Koppel told the rental company that it would cost $30,000, midrange for fentanyl cleanup.

The company balked. Executives told Ms. Spaulding-Koppel that their risk management team concluded they would rather clean the car themselves and hope no customers would be exposed.

It was a huge gamble by the rental car company, Ms. Spaulding-Koppel said. Exposure to less than 2 grams of fentanyl — a substance 25 to 50 times stronger than heroin — could kill an unsuspecting person who thinks it is merely sand.

“People need to understand the cost of cleanup, but they also need to understand the threat of fentanyl,” she said. “There is no forgiveness with it.”

Of the roughly 70,000 overdose deaths in the United States in 2017, more than 29,000 were linked to fentanyl and other dangerous synthetic drugs, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. That represents an 850 percent climb since 2013.

Fentanyl-fueled opioid deaths are moving out of private homes and into libraries, restaurants and other public spaces with alarming frequency. As the death toll climbs, so does the risk of secondary exposure causing an immediate overdose if fentanyl is inhaled, comes into contact with the mouth or eyes, or is absorbed through a cut or other opening.

Fentanyl exposure has claimed lives. In May, a Florida couple were arrested after their infant died of fentanyl and cocaine exposure. Police said the infant’s mother was wearing multiple fentanyl patches that had been cut in half, allowing a lethal amount of residue to spill onto the child.

“I find it shocking how lightly we are taking this threat,” said Amit Kapoor, CEO of First Line Technologies, a Virginia chemical company that promises its product Dahlgren Decon can neutralize fentanyl. “It is a big, emerging threat. If someone got their hands on this, it’s pretty incredible what they could do.”

Dahlgren Decon is licensed by the Navy and was developed to clean up after chemical warfare attacks. Mr. Kapoor discovered its application for opioids after testing it on fentanyl in a lab. He now sells it to state and federal first responders and law enforcement agencies as well as a handful of private companies.

Despite the explosion of fentanyl, no cleanup standards have been established to determine when a fentanyl-tainted property is safe. Compounding the problem are cleanup costs that homeowners can’t afford and insurers refuse to pay. Businesses would rather risk a lawsuit than deal with the costly out-of-pocket expenses or rising insurance premiums.

“There are several 600-pound gorillas in the room that we are dealing with,” said Thomas Licker, president of the American-Bio Recovery Association. “It’s a bit of a nightmare.”

Cleanup is complicated

Fentanyl decontamination is a difficult, cumbersome process, those in the industry say.

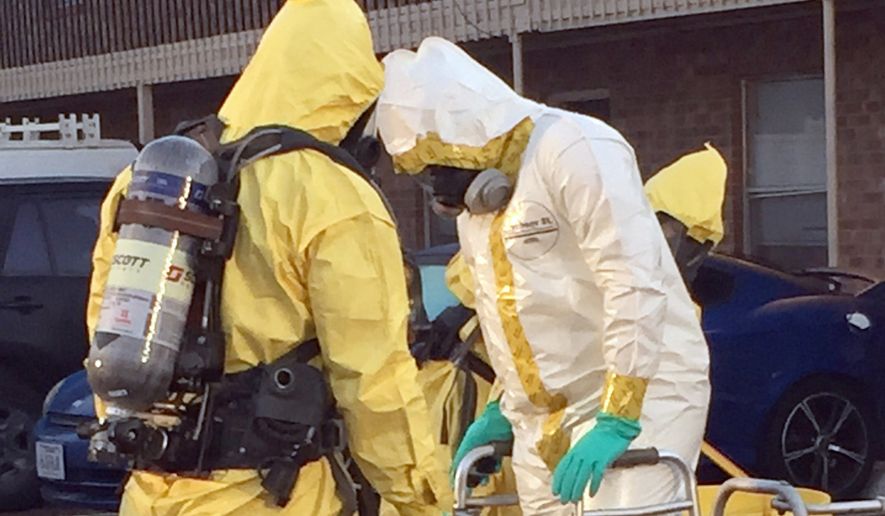

It requires a complete quarantine of the area and workers dressed head to toe in hazmat suits using high-efficiency vacuums designed to remove tiny particles from every square inch of space. After vacuuming, workers spray specialized chemicals to disinfect the area. Testing equipment is then used to ensure the fentanyl has been removed.

A job takes about 10 hours on average, including breaks every 20 minutes because of blazing temperatures inside the hazmat suits. Jobs typically cost about $400 per hour, with a total price tag ranging from $30,000 to $50,000. One reason for the expense is that the specialized vacuums, which cost as much as $1,200, must be incinerated after cleanup.

“The cost of remediation jobs tends to be expensive, but it includes training expenses and everything else needed to do the job right,” Mr. Licker said. “We make money doing it, but we are the ones risking our lives.”

Rarely covered by insurance

Most homeowners can’t afford the bill, and few insurance policies cover what the companies consider an intentional criminal act. The debate rages on, leaving the public at risk.

“This is an uphill battle because insurance companies are doing whatever they can not to cover it,” Ms. Spaulding-Koppel said.

Chris Hackett, senior director of personal lines for the Chicago-based Property Casualty Insurers Association of America, said most insurers won’t cover any damage or pollution resulting from an intentional or criminal act.

“If a policy says it is not going to cover any criminal acts, that is going to include meth, fentanyl and any other drug you can think of,” he said. “Sometimes it’s better to have general language excluding that stuff rather than a laundry list of items.”

The public and businesses aren’t the only ones affected. Westport, Massachusetts, Police Chief Keith A. Pelletier said the cost of decontaminating police cars and holding cells after fentanyl exposure is draining his budget. It is typically cheaper to buy a new police car than to have a contaminated one cleaned.

In the dark

Also putting the public at risk is the lack of disclosure laws surrounding overdoses, including those involving fentanyl. No law on the state or federal level forces homeowners to notify potential renters or buyers that an overdose occurred on the property.

The fight parallels the methamphetamine crisis last decade, when lawmakers received pushback because revealing that a house was once used to make the drug would lower its value. A decade later, only 23 states have laws requiring homeowners to disclose that their house was once a meth lab. No such measure exists on the federal level.

Indiana state Rep. Wendy McNamara, a Republican, had her meth disclosure bill passed in 2014 after years of fighting for it. She called the process “extremely difficult.”

She would have to write a new bill for fentanyl disclosure rather than expand the methamphetamine law under rules of the Indiana legislature. She isn’t sure state lawmakers are ready for the battle, given all of the other debates about the opioid crisis.

“This is a legitimate concern for a lot of folks,” she said. “But we are focused so much on trying to stop opioid usage and rehabilitate folks, this is a piece that has gotten lost in the bigger picture of trying to fight the entire opioid epidemic.”

Ms. McNamara said local real estate associations partnered with her on the bill. But in other states, such groups fiercely opposed the legislation.

The Iowa Association of Realtors fought a meth disclosure bill introduced in January 2014. At the time, the group said the issue was too complex to address through a law because some properties used as meth labs require only light remediation, while drywall needs to be removed in other cases.

“It’s a different train of thought,” Mr. Licker said. “Ours is focused on public health, and theirs is to sell houses.”

Wesley Shaw, a spokesman for the National Association of Realtors, said his agency has no policy on meth or fentanyl disclosure and that enacting laws is a state issue.

“Regardless, disclosure is an important aspect of consumer protection, and the duty to disclose known defects does extend to real estate professionals,” he said. “NAR believes that any known factors that can affect the value of desirability of a property should be disclosed.”

Federal lawmakers have not tackled the issue, which Mr. Kapoor is trying to change.

“We’ve been trying to educate the folks on Capitol Hill about this threat,” he said. “They are more focused on fentanyl detection, but the bigger challenge is, ’How do you neutralize it?’”

Businesses and other public entities don’t have to disclose overdoses either. In Pennsylvania, overdoses occurred in 12 percent of libraries last year, including four at one Philadelphia library alone, according to a University of Pennsylvania study.

Mr. Kapoor said his company is responding to fentanyl exposure in rental cars, fast-food restaurants and hotels rather than private homes.

Mr. Pelletier said his officers responded to a fentanyl overdose at a midlevel chain hotel. He urged hotel management to hire a remediation company to clean the room. They told him the maids would handle it.

“We took precautions, but I’m worried about the public,” he said. “I know a family with kids stayed in that room afterwards, but is there even a protocol for cleaning fentanyl in a hotel room?”

• Jeff Mordock can be reached at jmordock@washingtontimes.com.

Please read our comment policy before commenting.