The Senate on Tuesday approved the most sweeping prison reform bill in years, voting to cut sentences of tens of thousands of inmates while also boosting access to programs designed to keep them from ending up back behind bars again.

The measure cleared on an 87-12 vote and marks a major bipartisan victory for President Trump, who had pressured GOP leaders to pass it this year, before lawmakers closed down Congress.

It still needs approval in the House, where a vote is expected this week.

“This prison and sentencing reform bill is a much-needed first step toward shifting our focus to rehabilitation and reentry of offenders, rather than taking every person who ever made a mistake with drugs, locking them up, and throwing away the key,” said Sen. Rand Paul, a Kentucky Republican who had made a crusade out of reforming sentencing.

Dubbed the First Step Act, the legislation would expand prison programs designed to reduce recidivism and allow some prisoners to earn credits toward early release by taking part in those programs. The bill also reduces some maximum mandatory sentences, such as ending the three-strikes life-in-prison penalty and replacing it with a 25-year maximum.

Backers said the credits would earn inmates a faster opportunity to enter a halfway house or be put on home detention.

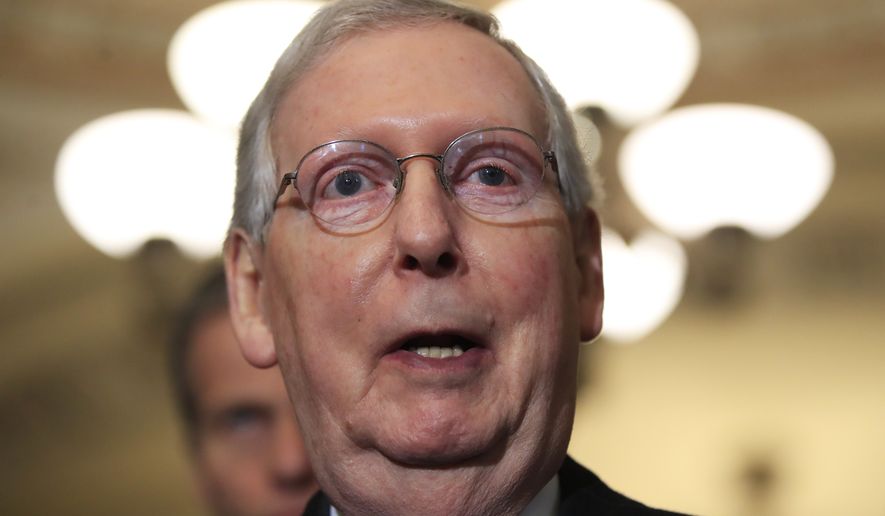

The bill drew a stunning coalition, with even Senate Majority Leader Mitch McConnell signing on. He had been the chief hurdle to getting the bill on the floor but had finally relented earlier this month after Mr. Trump lobbied him.

Also signing on were the chamber’s most liberal members, who lamented that the bill didn’t go far enough in reducing sentences, but said the chance for some inmates to get out early was an important step.

The core of the deal was written by Sens. Chuck Grassley, the Republican chairman of the Judiciary Committee, and Richard Durbin, a senior Democrat.

The bill applies only to federal prisons, which hold far fewer people than state prisons.

It includes new rules on keeping inmates in facilities close to their homes where possible and pushes for them to be put in home confinement for the maximum time allowed.

An early version of the bill would have released an average of 53,000 federal inmates a year over the next decade, according to the Congressional Budget Office. That would be more than a quarter of the current inmate population.

Last-minute changes made to win over key conservatives likely will reduce the releases by limiting the crimes eligible to earn time credits.

Some Republicans had tried to strengthen the bill even further with amendments on the Senate floor Tuesday.

One amendment would have improved notification to victims of a criminal’s impending release under the new law and given them a chance to lobby the warden, who could veto the release.

Another amendment would have limited convicts eligible for good-time credits by preventing those whose crimes involved the risk of force against people or property from taking advantage.

Sen. Tom Cotton, the chief sponsor, said he was trying to prevent bank robbers and carjackers from getting out of prison early.

“The First Step Act provides hundreds of new rights and privileges to federal prisoners. More phone time, reduced sentences, ’compassionate release,’ and early release credits. There is not a single benefit in the bill for the victims of these criminals,” Mr. Cotton said.

The bill’s backers, though, said his changes would have scuttled the bipartisan deal, cutting too many people out of the chance to score early release. The amendments were handily defeated.

• Stephen Dinan can be reached at sdinan@washingtontimes.com.

Please read our comment policy before commenting.