Robert E. Lee remains defiant in the U.S. Capitol, where his statue stands in a place of honor a year after the race-tinged clashes in Charlottesville, Virginia, brought renewed attention to him and other figures of the Confederacy.

Efforts to oust him have come to nought, with Lee’s opponents running into roadblocks both legal and political.

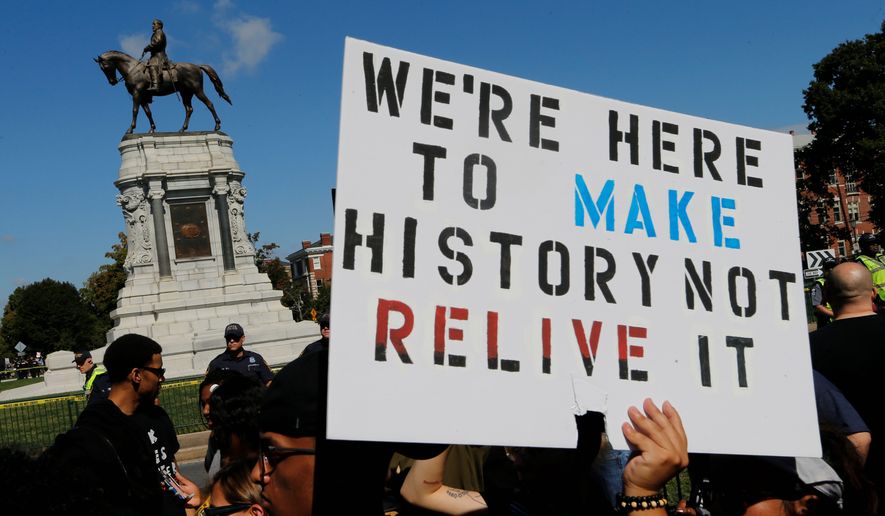

The same is true in Charlottesville, where the bronze statue of Lee astride his horse Traveler sits, despite having been the spark in the Aug. 12, 2017, violence that left one counterprotester dead, a dozen people on both sides facing charges, and a country wondering how the wounds of the Civil War could still run so deep.

In both cases, the common factor is Virginia. A state law has prevented Charlottesville from taking down the statue, and it was the state legislature that sent the Lee statue to the Capitol early last century as part of the state’s two donations to the Statuary Hall collection.

Attempts by black members of Congress to pass legislation kicking Confederate statues from the national collection went nowhere.

And in Virginia, state Delegate Mark H. Levine saw his efforts to get Virginia to recall the Lee statue from the Capitol die in committee in the GOP-run legislature.

He said he’s now looking ahead to the next state elections in 2019, when all of the General Assembly is up for election and Democrats have a good chance to flip both chambers.

“I don’t think this legislation is dead. I thin once the Democrats take over, we’ve got a good chance to do it,” Mr. Levine said.

He said his goal isn’t to punish Lee, a conflicted character in state history, but rather to make the point that he’s not one of the two greatest Virginians — particularly from the perspective of the nation’s capital, which his troops tried to encircle and capture during the war.

Mr. Levine isn’t wedded to a replacement, suggesting a commission should be formed to announce an alternative to Lee.

“The statue of Lee in the Capitol is not about history, except to the extent it tells us something about [1909], and if we take it down in 2020, tells us something about 2020,” he said.

Lee’s defenders said Mr. Levine gets it wrong when he says Lee isn’t a top-tier Virginian.

“He’s probably a transplant,” said Bragdon Bowling, a Richmond-area resident and veteran of numerous Civil War heritage fights. “Native Virginians revere Lee.”

He said those pushing to remove the Confederate statues are part of a left-wing movement, calling them “some really evil people.” He said they’re risking Virginia’s heritage along the way and threatening a major source of tourism.

Mr. Bowling said he doesn’t agree with some of the more extreme elements on the right who have rallied in favor of the statues — though he said he supports their right to protest.

“I just wish they wouldn’t,” he said. “I don’t think Virginia needs them.”

In Charlottesville, the Lee statue in a city park was the spark for last year’s clashes. Right-wing and white supremacist activists staged a rally to defend the statue against the city’s attempts to pull it down — drawing an even bigger crowd of left-wing and minority-rights protests.

Violence ensued, and one woman, a counterprotester, was killed in the aftermath, struck by a car driven by a man police say was one among the white supremacist marchers.

A judge has prevented the city from taking down the statue while he decides whether it’s protected under state law prohibiting localities from pulling down a war memorial. The judge also ordered Charlottesville to remove a tarp it had draped over the statue for months after the clashes.

“We’ve protected the monuments, but our injunction so far is only temporary,” said Jock Yellot, executive director of the Monument Fund, which is battling to save the statue. “The judge has to decide whether to make it permanent,”

The survival of the Capitol and Charlottesville bronzes — the two most prominent targets after last year’s clashes — is all the more striking given the success of Confederacy critics in removing others.

Lee and fellow Confederates were pulled down in Baltimore, New Orleans, Dallas and more than two dozen other cities.

Even the church Lee attended in Lexington, Virginia, is no longer R.E. Lee Memorial, but reverted to Grace Episcopal Church. And a plaque to Lee’s memory was also torn down from Christ Church in Alexandria, where he once attended services and where a pew is still dedicated to his family. The Southern Poverty Law Center recorded 1,740 public Confederate symbols as of late July 2017, just before the Charlottesville clashes. Since then, 73 have been taken down.

“We’ve seen a remarkable effort to remove Confederate monuments from the public square, yet the impact has been limited by a strong backlash among many white Southerners who still cling to the myth of the ’Lost Cause’ and the revisionist history that these monuments represent,” said Heidi Beirich, director of the SPLC’s Intelligence Project. The Lee Capitol statue was controversial from the start.

Virginia’s decision to commission it in 1903 sparked a heated debate in the newspapers, and veterans of the Grand Army of the Republic adopted resolutions demanding Congress refuse it.

Then-Rep John F. Lacey, born a Virginia but an Iowa congressman at the time of the debate, wrote a letter predicting today’s debate, saying the country would always wonder why Virginia had chosen Lee over other luminaries.

“If Virginia suffered from any poverty of great names and found difficulty filling the place it might be different,” he said.

Indeed, Virginia accounted for four of the first five presidents, the most iconic chief justice in John Marshall, and Revolutionary War-era figures such as George Mason and Patrick Henry. Thomas Jefferson already has a statue that’s not part of the state collection, but Madison and Monroe have long been options for those seeking a viable alternative to Lee.

Congress would finally accept the Lee statue along with Washington in 1934.

• Stephen Dinan can be reached at sdinan@washingtontimes.com.

Please read our comment policy before commenting.