BOGOTA, Colombia (AP) — The young protégé of a powerful former president is being sworn in as Colombia’s new leader Tuesday, tasked with guiding the implementation of a peace accord with leftist rebels that remains on shaky ground.

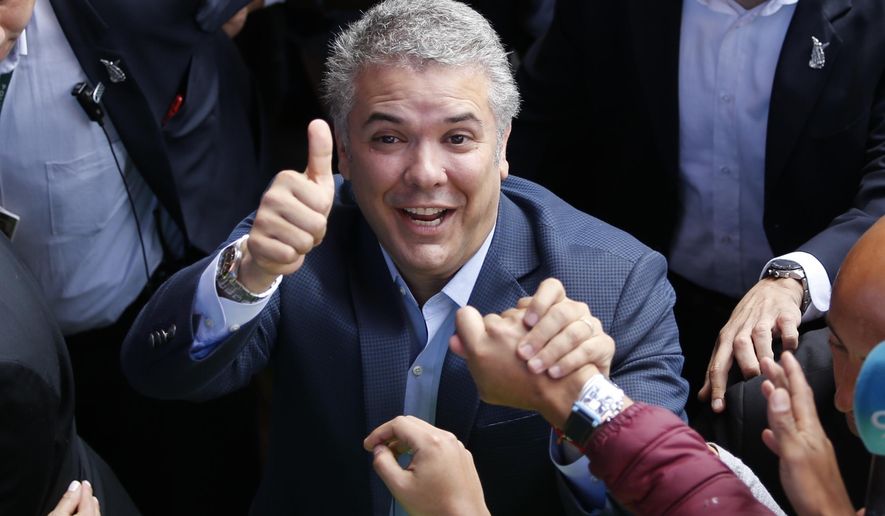

Forty-two-year-old Ivan Duque will be the youngest Colombian chief of state ever elected in a popular vote when he is sworn into office at Bogota’s Plaza Bolivar.

The prematurely graying father of three describes himself as a centrist who will unite the nation at a time when many are still fiercely divided over the peace agreement that ended more than five decades of bloody conflict.

His detractors fear he will be little more than a puppet for Alvaro Uribe, the conservative ex-president who led a referendum defeat of the initial version of peace accord in 2016. Uribe is still backed by millions of Colombians, though he is perhaps equally detested by legions who decry human rights abuses during his administration.

Duque is taking Colombia’s presidency at a critical juncture: Coca production is soaring to record levels, holdout illegal armed groups are battling for territory where the state has little or no presence and a spate of killings of social activists has underlined that peace remains a relative term.

“If Duque is not able to solve this problem and find a way to bring the state into the countryside, we’re going to keep having the same problems we’ve had for decades,” said Jorge Gallego, a professor at Colombia’s Rosario University.

Duque is the son of a former governor and energy minister and friends say he has harbored presidential aspirations since early childhood. But his rise from unknown technocrat to a popular senator and now president has been extraordinarily rapid, propelled in large part by the support of his mentor, Uribe.

Just four years ago, Duque was a Washington suburbanite with a cushy job at an international development bank. It was there that he developed close ties to Uribe, assisting the former president when he taught a course at Georgetown University. Later Duque helped Uribe lead a United Nations probe into Israel’s deadly attack on a Gaza-bound aid flotilla and helped him write his memoir.

Then in 2014, Uribe propelled Duque into the political limelight when he encouraged him to return to Colombia to run for a Senate seat and placed him on a list of newcomer candidates that he urged his multitude of supporters to elect.

Within Uribe’s conservative Democratic Center party, Duque’s reputation as a more moderate voice can at times put him at odds with the solidly right-wing faction. Uribe’s support is thus considered crucial for Duque to rule with the full backing of his party. But he will need to build a broader alliance to pass laws in Congress.

Duque’s dependence on Uribe has sparked concern from critics, though analysts believe the former leader’s mounting legal troubles could provide the incoming president a new degree of independence.

Uribe briefly stepped down from the Senate in July after the Supreme Court asked him to testify on allegations of bribery and witness tampering in a case related to claimed ties to paramilitaries, which he vehemently denies. Uribe later reversed course and withdrew his resignation letter.

In the weeks since Duque’s resounding victory over leftist ex-guerrilla Gustavo Petro, the president-elect has signaled both his loyalty to Uribe and a conviction to chart his own path. While many of his Cabinet picks have ties to Uribe, there are also a number of incoming ministers with no links to a traditional political party.

“So far I think he has shown more independence than some sectors believed,” Gallego said. “Treating Duque as a puppet of Uribe is a very simplistic way of analyzing things.”

At the top of Duque’s agenda are likely to be Colombia’s economy and the peace agreement as well as reversing coca production that last year reached levels unseen in more than two decades of record keeping and $10 billion in U.S. counter-narcotics work. The soaring coca levels have tested traditionally close ties with the United States.

Throughout his campaign, Duque promised to push changes in the peace agreement, including creating tougher penalties for former leaders of the now defunct Revolutionary Armed Forces of Colombia responsible for crimes against humanity. Under the accord, most rebels who fully confess their crimes will be spared any jail time, a sore point for many Colombians who still vividly remember the atrocities of war.

Colombia’s conflict between leftist rebels, the state and paramilitary groups left at least 260,000 dead, some 60,000 missing and millions displaced.

While some fear Duque’s anti-accord rhetoric and proposed changes could further destabilize what has already been a slow and tumultuous implementation, others hope that in the long-term the agreement could enjoy broader support from a divided Colombian society if led by someone with a critical approach.

Cynthia Arnson, director of the Latin America program at the Woodrow Wilson International Center for Scholars in Washington, noted that Duque’s rhetoric on the peace accord has softened somewhat since his election.

“There was a sense that because Uribe had campaigned so strenuously against the peace agreement that Duque was going to come into office and just rip the thing apart,” she said. “I don’t think that that’s likely.”

Please read our comment policy before commenting.