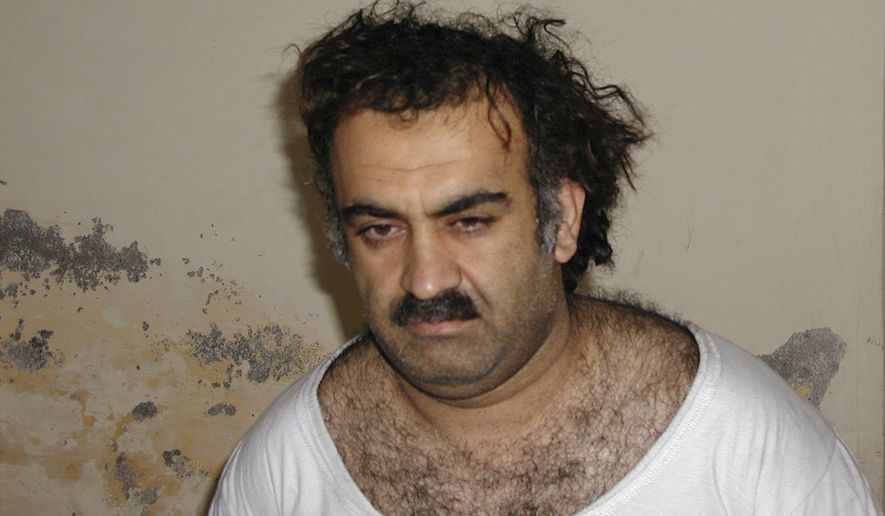

Tami Michaels came face-to-face with accused 9/11 mastermind Khalid Sheikh Mohammed inside a military commission court at Guantanamo Bay in May during yet another round of seemingly endless pretrial hearings.

Inside the room, Ms. Michaels — an interior designer and radio host from Seattle who could be called as a witness in the case — said she watched as the defense team for the al Qaeda militant stalled for time and looked for any reason to further drag out an already painfully long process.

Although defense attorneys vehemently denied that was their strategy, Ms. Michaels came away from the hearing frustrated and fearing that the trial of Mohammed, charged with a host of crimes including murder, conspiracy and terrorism in connection with the Sept. 11, 2001, attacks, is doomed to exist in a permanent legal limbo.

“It was infuriating,” she told The Washington Times last week. “I feel like they’re grandstanding. I saw it with my own eyes. … It’s time. It needs to go forward now.

“We want a day in court,” she said. “We want the names [of those killed on Sept. 11] said in that courtroom.”

Ms. Michaels and her husband, Guy Rosbrook, were in New York City that fateful day in 2001, holed up across the street from the World Trade Center in their Millennium Hotel room after the first plane made impact. From there, they used a handheld camera to record gruesome video of the burning buildings, the chaos around ground zero and people falling to their deaths from the towers.

The video, which has never been made public and was given to authorities within days of the attack, was used by federal prosecutors in 2006 in the conviction of Zacarias Moussaoui, the so-called 20th hijacker. He was found guilty of conspiracy to commit murder and other offenses. Ms. Michaels also testified in the Moussaoui case.

The couple’s video footage, which they described as disturbing and difficult to watch, could play a similar role in the Mohammed trial.

Endless delays

There is no indiction of when that trial will begin, if it goes forward at all. Despite having been captured in 2003 and first charged more than a decade ago, Khalid Sheikh Mohammed has yet to receive a trial date. Defense Department officials overseeing the military commission proceedings can offer little in the way of a timeline.

“Pretrial proceedings began in 2012 and will continue until trial is ready to commence. As the rulings in pretrial matters can directly impact trial timing, any prediction of a start date at this point would be speculative,” Cmdr. Sarah Higgins, a Pentagon spokeswoman, said Thursday.

What Ms. Michaels and other critics view as grandstanding, defense attorneys argue is an effort to ensure Mohammed gets the fair trial he deserves under U.S. law. Among other things, they contend that much of the evidence U.S. officials gathered during interviews with Mohammed was gained through torture and that they haven’t been given clear answers from the federal government on what role “enhanced interrogation techniques” played in getting a confession.

“We’re doing what’s necessary to make the case be a fair prosecution,” Mohammed’s lead attorney, David Nevin, told Vice News in May. “It doesn’t make any difference how big the case is, how awful the circumstances of 9/11 were. It’s a criminal prosecution in the United States of America, and it has to be fair.”

Mr. Nevin argued that the charges against Mohammed contain numerous technical problems, mainly that he is charged with “murder in violation of the law of war” and similar crimes.

“There was no war on Sept. 11,” he said.

Legal analysts say the Obama administration’s decision to conduct the trial via military commission rather than transferring Mohammed and his co-defendants into the civilian justice system led to the stalemate. President Obama and Attorney General Eric H. Holder Jr. initially favored moving the trial to a civilian court, a piece of a much broader policy goal of closing the Guantanamo detainee site altogether.

But faced with bipartisan pressure from Congress and the public, the administration eventually changed course. Mr. Holder announced in 2011 that Mohammed would face a military trial.

That move, analysts argue, has allowed the defense team to turn the spotlight to torture and other suspected abuses in the aftermath of Sept. 11. The U.S. has acknowledged that Mohammed was held in secret overseas prisons after his capture, and his attorneys say he was subjected to waterboarding and other cruelties.

“The bottom line here is torture,” said Karen J. Greenberg, director of the Center on National Security at Fordham University School of Law. “That hearing [in May], for crying out loud, every place they tried to move, torture, in expected and unexpected ways, gets in the way.”

It’s unlikely that dynamic will change. Mr. Nevin told the British newspaper The Guardian last fall that it is possible “my client will die in prison” before the trial ever begins. Mohammed, accused of having conceived the Sept. 11 attacks on New York and Washington, is 53 years old.

Ms. Greenberg suggested that’s a real possibility and that the military commission process has gone so far off the rails that it will be virtually impossible to put it back on track.

“I see endless delays that will play out forever,” she said. “These are the forever defendants.”

’They were on fire’

Ms. Michaels said the prosecution attorneys in the case are doing the best they can in a nearly impossible situation. Among other complicating factors, Mr. Nevin and other members of the defense team regularly grant interviews to the media, while the prosecution team for the most part has been silent, allowing just one side of the narrative to reach the public.

“This team of prosecutors are selfless, determined and patriotic,” Ms. Michaels said. “They will never forget” the Sept. 11 victims.

Those prosecutors have at their disposal thousands of hours of interviews with Mohammed and other materials that they say detail his work in planning the Sept. 11 attacks. In seeking a conviction, their strategy requires ensuring that the horror of that day hasn’t faded from memory after 17 years.

“For all intents and purposes, this chapter of [the 9/11 era] is coming to an end. It started with the death of [Osama] bin Laden [and] the decimation of [the Islamic State in Iraq and Syria] as an offshoot of al Qaeda,” said Ms. Greenberg, adding that popular demands to bring the remaining perpetrators to justice will continue to fade over time.

As was the case in the Moussaoui proceeding, the government likely will use video as a reminder of the brutality of the attacks and to prove that the victims were, as a legal matter, murdered.

Ms. Michaels said their video, along with their eyewitness accounts, prove that in graphic detail.

“We saw the people who chose to jump, and those who were forced to jump. … There were those who are absolutely blown out by fire,” she said. “They were murdered. That’s the word I want. ’Jumping’ sounds like they had a choice. For the people who were forced out of the building that day, there was no other choice. They were on fire.”

• Ben Wolfgang can be reached at bwolfgang@washingtontimes.com.

Please read our comment policy before commenting.