OPINION:

Police officers, intelligence agents, national security experts and others in the business of providing protection may swear by the benefits of facial recognition software — may insist that the technology tool gives them unrivaled abilities to track suspects and halt criminals and terrorists in their tracks, oftentimes before the crimes are even committed. But there’s a law of unintended consequences at play here.

Where else will this technology be used?

Congress found one answer to that question the hard way after the American Civil Liberties Union put Amazon’s “Rekognition” software to the test and found the A.I.-driven program mistakenly labeled 28 lawmakers as criminal suspects. Legislators soon after called CEO Jeff Bezos to the carpet, demanding he explain the error.

But if members of Congress can be so grossly maligned, just think of the possibilities for mischief when this technology’s applied to the rest of us — to the lesser-knowns of the country. Artificial intelligence, after all, is only as good as its programmers.

Whatever biases are inherent in humans are bound to manifest in the technology, too.

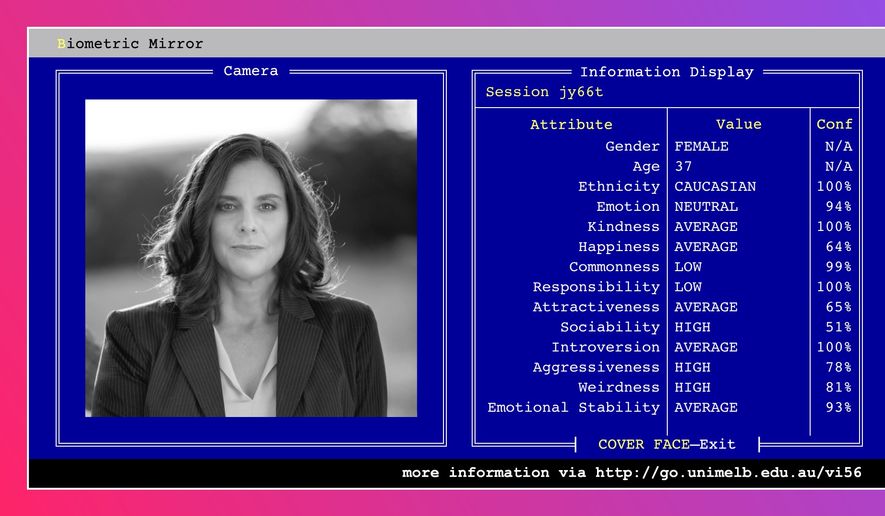

To help make this point, Niels Wouters and his team of Melbourne, Australia, researchers created the Biometric Mirror, a facial recognition program that takes a photograph of a human face, analyzes it, and spits out 14 key characteristics about that person, from happiness to sociability.

Its accuracy is negligible. But then again, that’s the point.

“Indeed,” Wouters said, “Biometric Mirror shows how the [facial recognition] technology is currently still in its infancy.”

To arrive at its ratings, Biometric Mirror uses data previously fed it from 33,430 volunteering humans who analyzed 2,222 photographs of faces and scored them on these same 14 traits. In other words, if the majority of the humans who participated in the research project thought a certain type of facial expression reeked of, say, aggressiveness, then so, too, will Biometric Mirror.

Fun and games? On one hand, yes. On the other, raise the red flags and sound some gongs.

To test Biometric Mirror’s biases, and to see how artificial intelligence might rate my personality based on a snapshot, I submitted a photo to Wouters for analysis. The findings were interesting, particularly the parts where I scored low for responsibility, average for introversion and high for sociability, aggressiveness and weirdness.

Truly, responsibility is my middle name, and on the socialization and extroversion fronts, I’m about one up from a hermit. As for weirdness — who can say. This is how Biometrics Mirror researchers defined this category, on their web page: “Weirdness displays the estimated public perception … reflecting a striking oddness or unusualness, especially in an unsettling way.”

Perhaps Biometric Mirror found my aggressiveness to be so unsettling?

“Important to note is that Biometric Mirror is seen as a ’fun’ experience,” Wouters said. [But] imagine you score low on responsibility and this would make you ineligible for management positions.”

Yes, imagine that. Imagine this, too, that a high score on aggressiveness might make you an automatic suspect to police.

Then there’s this, from Wouters: “At the end of the week, when I haven’t shaved my beard, I turn out to be 10 years older and more aggressive than on a Monday morning. Similarly, smiling will bring someone’s ratings into the higher values.”

That’s right — photos can lie.

These biases, depending on how facial recognition technology is used, carry real consequences. They’re potentially damaging and harmful to the individual. Yet the race to bring facial recognition technology into the mainstream goes forth, and with discomforting rapidity.

Faception, for example, a private personality profiling company founded in 2014, now uses machine learning technology to help companies screen employees, law enforcement surveil street scenes, security agents scope out crowds.

On its website, the company even promises it “goes beyond Biometrics. Our solution analyzes a person’s facial image and automatically reveals his personality.”

That’s unsettling.

America, as Biometrics Mirror demonstrates, should go slow in the commercial roll-out of facial recognition technology. It’s one thing for Congress to be called out as a pack of criminals. It’s quite another for both private and public sectors in this country to use facial recognition to determine somebody’s job worth, or propensity to commit an illegal act, or ability to serve in particular role.

Indeed, left to a machine to decide, my own job prospects going forward could very well be on shaky ground.

• Cheryl Chumley can be reached at cchumley@washingtontimes.com or on Twitter @ckchumley.

Please read our comment policy before commenting.