ATHENS — After spending 10 years in maximum security prisons in Turkey — including stints of isolation and torture — Turgut Kaya, a prominent local journalist and dissident, decided it was time to flee.

Like thousands of his fellow Turks in recent years, his destination was nearby Greece, which has traditionally had a complicated and wary relationship with its neighbor across the Aegean.

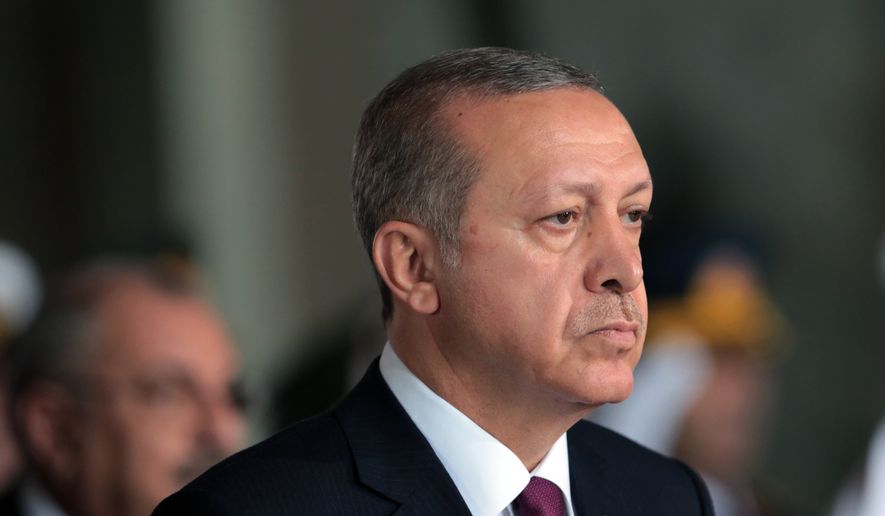

“It’s not just me,” the 45-year-old Mr. Kaya, recently given asylum after a 55-day hunger strike, said at an Athens cafe. Turkish President Recep Tayyip Erdogan “is attacking students, academics, teachers and many other people that have no relations with any of the organizations he considers his enemies.”

“They don’t have any proof to go after me or these people — even judges are now in prison or exile,” he said.

Since surviving a coup attempt in July 2016, Mr. Erdogan has intensified a crackdown on Turkish journalists and domestic critics like Mr. Kaya. But critics say the sweep has been all-encompassing and massive and has ensnared thousands of people from all walks of life.

As of July, tens of thousands of Turks were in prisons and more than 100,000 investigations had been launched against members of the military, teachers, lawyers, doctors, and even Supreme Court justices and prosecutors, who are suspected of either being members of Kurdish separatist organizations or are linked to an organization headed by exiled, U.S.-based cleric Fethullah Gulen, a onetime ally of the president whom Mr. Erdogan now accuses of masterminding the failed coup.

“It’s definitely a witch hunt,” said Spyros Sofos, a researcher at the Center of Middle Eastern Studies at Lund University in Sweden. “Everyone in the opposition is being criminalized. Also, anyone with a personal animosity against someone else can just accuse them of being a member of [Mr. Gulen’s organization] or the Kurdish organizations, and because no one is willing to investigate the claims, these people are easily included in the list of suspects.”

As a result, the numbers of Turkish citizens applying for asylum in Greece skyrocketed from just over three dozen in 2015 to 1,827 in 2017 and 1,152 in the first six months of this year.

More than 3,000 Turkish refugees have settled mostly in Athens and Thessaloniki, a city close to Turkish hearts as the birthplace of Kemal Ataturk, the founder of the modern Turkish state. Thessaloniki also boasted a Turkish enclave until the 1920s, when a population exchange between the two countries took place.

Some, like Mr. Kaya, apply for political asylum. Others come with student visas or have work permits. And the better-off buy property: Some 1,000 Turks have bought homes valued at at least $283,000, the minimum necessary for buyers to get the European Union visa that enables them to stay in Greece and secure the right to freely move around other EU countries.

Some, like Serkan Zihli, 38, say Greece is an obvious choice because of its proximity to Turkey.

Mr. Zihli, who until three years ago co-owned an Istanbul public relations company that employed 10 people, said he knew he would be targeted by the Erdogan government. He had participated in protest in 2013 against the president’s plans to turn a central Istanbul park into a mall. The protest later turned into a nationwide movement that badly rattled the government.

Mr. Zihli was highly visible in the protests, widely quoted in the media and followed on Twitter. He was prosecuted under laws against insulting the president. Then came the visits by tax authorities to his business, visits he believes was deliberate harassment.

Mr. Zihli decided to sell everything and move to Greece, where he found a job and where his family can visit because of its easy travel connections.

“I was sued for insulting the president and the government on Twitter even though I was just criticizing the government,” he said. “But you can get prosecuted even if you just retweet something. … This is done to frighten ordinary people. I’m never going back to Turkey.”

The surge in asylum claims has resulted in further tension between the two countries. Mr. Erdogan is demanding extradition of the asylum-seekers, including an Interpol arrest warrant this month targeting Mr. Kaya. The Greek Justice Ministry refused, even though a Greek court approved the extradition.

Mr. Erdogan has been using such cases to boost his own political base, and exiles like Mr. Zihli are bracing for a long period away from home. Mr. Zihli works in customer support at an Athens telecommunications company and acknowledges he is vastly underemployed.

“This is the only job that I can do here because they provide me with the visa,” said Mr. Zihli. “[I’m in] an entry-level position, thanks to Erdogan. But the most important thing is I’m free.”

Please read our comment policy before commenting.