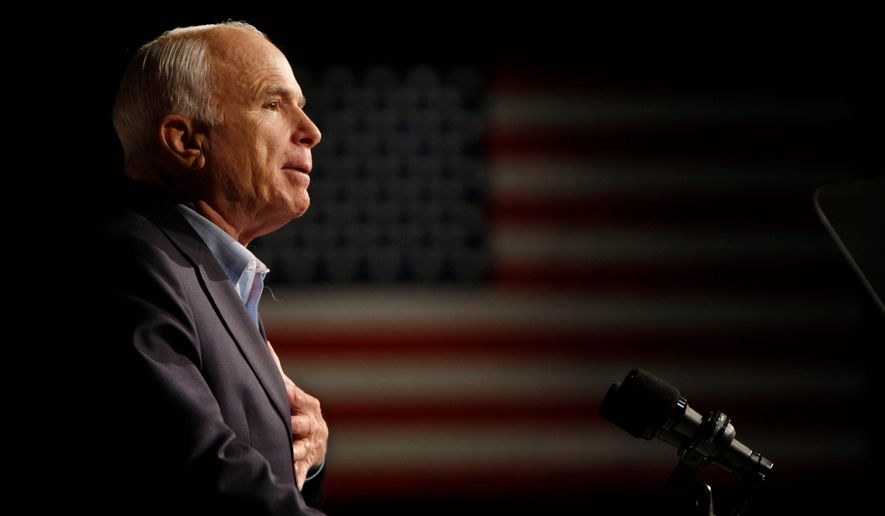

Many people have disproved F. Scott Fitzgerald’s axiom that there are no second acts in American lives. But Sen. John McCain proved there can be third and even fourth acts.

Mr. McCain, a veteran of the Vietnam War with more than 35 years in Washington, two presidential campaigns and countless personal and political revivals, died Saturday after a yearlong bout with brain cancer, leaving a legislative legacy unmatched by any other Republican of his generation.

“John McCain is one American who will never be forgotten,” said Arizona Gov. Doug Ducey. “He was a giant. An icon. An American hero.”

Mr. McCain’s family announced Friday morning that he was ending his cancer treatments, saying “the progress of disease and the inexorable advance of age render their verdict.”

Flags across the country were lowered to half-staff, and the U.S. Capitol and the Arizona Statehouse made plans for Mr. McCain to lie in state this week, as his colleagues sought ways to pay respect.

His return to Washington will be his first since December, when he cast his last votes before taking a long absence to battle the disease from his home near Sedona. He used his final months to complete one last book, welcome visitors from among the political elite and weigh in from afar about the goings-on in Washington.

SEE ALSO: John McCain to lie in state at U.S. Capitol Rotunda

President Trump and Russian President Vladimir Putin were favorite targets for the ailing senator, who saw them as dangerous to the international order. He cheered on colleagues as they worked to complete the annual defense policy bill — this one named in his honor — faster than it had been done in decades.

Mr. McCain was one of the few grandees who managed to transcend party, serving at times as a loyal Republican and other times as a massive thorn in the side of the party. He staked out issues that won him adulation from a liberal press and made him a popular legislative companion for Democrats, even as his own party leaders steamed.

One of his final votes in the Senate was dealing the fatal blow to Mr. Trump’s plan to repeal Obamacare.

Tributes poured in from political allies and opponents, who called Mr. McCain irreplaceable.

“Few of us have been tested the way John once was, or required to show the kind of courage that he did. But all of us can aspire to the courage to put the greater good above our own. At John’s best, he showed us what that means,” said former President Barack Obama.

Sen. John Thune, South Dakota Republican, called Mr. McCain “one of the most courageous men of the century.”

SEE ALSO: John McCain, Ali found common ground despite differences

Sen. Ben Sasse, Nebraska Republican, said simply: “Our nation aches for truth-tellers. This man will be greatly missed.”

’The Punk’

Mr. McCain showed an early talent for winning friends and infuriating people at Episcopal High School in Alexandria, Virginia, where the yearbook dubbed him “The Punk.”

“His magnetic personality has won for him many life-long friends. But, as magnets must also repel, some have found him hard to get along with,” the editors concluded.

Also clear from the start was that Mr. McCain was headed for Annapolis and a life in the Navy, where he was a legacy. His father, Adm. John S. McCain Jr., attended. So did his father’s father, Adm. John S. McCain Sr. Like them, Mr. McCain fought the rules and regimentation of the school and came in near the bottom of his class.

His path to naval greatness took a detour through Vietnam, where he repeatedly sought combat duty, surviving the fire on the USS Forrestal before he was shot down while on a bombing mission on Oct. 26, 1967.

His North Vietnamese rescuers first bayonetted him and smashed his shoulder, then took him to the infamous prisoner of war camp dubbed the “Hanoi Hilton.” Beatings were frequent over the next 5 years, and he was tortured into making an anti-American propaganda “confession” at one point. Yet after his father was made commander of all American forces in the Vietnam War and his captors offered him early release, hoping for a propaganda victory, he refused.

Released in 1973, Mr. McCain stayed in the Navy and eventually wound up in Washington as a service liaison to Congress.

With chances for advancement in the Navy dim, his time on Capitol Hill set him on the path to a second career in politics. Along the way, he divorced his first wife and quickly married Cindy Hensley, who was from Arizona.

Career in Congress

Mr. McCain won election to a U.S. House seat from Arizona in 1982 and won his Senate seat in 1986, becoming one of the rare lawmakers whose influence ran from legislating to investigating to budgeting, and he excelled at each.

His name adorns the most important campaign-finance legislation in history, the 2002 McCain-Feingold law; he launched the investigation that exposed the corrupt dealings of megalobbyist Jack Abramoff; he led the effort to end interrogation tactics such as waterboarding that were used during the war on terror; and he railed against pork-barrel spending such as the “Bridge to Nowhere,” eventually helping end the practice of lawmakers tucking pet projects into massive spending bills.

“It’s pretty hard to think of any serious issues facing our nation without recalling the role John played,” Senate Majority Leader Mitch McConnell, Kentucky Republican, said after paying a visit to Mr. McCain in Arizona in early May.

His legislative dominance was matched by a personality that was at times gallant and other times truculent toward presidents, congressional colleagues, military leaders, Capitol Hill and administration staffers, and reporters.

That latter category he sometimes referred to as his “constituency,” a recognition of the on-again, off-again affair the American media had with the man they dubbed “the maverick.”

Reporters particularly loved chronicling Mr. McCain’s feuds with fellow Republicans, and it was the press that boosted Mr. McCain before and during the 2000 presidential campaign, then helped cement him as a legislative force on Capitol Hill. It helped that in many of his crusades, such as campaign finance or immigration reform, the battles he fought were in line with the editorial policies of the country’s dominant media establishment.

His penchant for bipartisanship went so far that in 2004 — in between his two runs for president as a Republican — Democrats sounded him out about being their vice presidential nominee.

He was also one of the country’s most ardent supporters of the men and women serving in the military, though the same could not be said for the top brass, who regularly faced withering questions from Mr. McCain in the Armed Services Committee, which he chaired at the time of his death.

Presidential runs

It’s a bizarre twist of history that America, which has loved its war heroes as presidents, elected three draft-avoiders from the Vietnam era to the Oval Office while rejecting two major-party nominees who served, in John F. Kerry, the former senator and secretary of state, and Mr. McCain.

The first of Mr. McCain’s rejections came in 2000, when he faced off against Texas Gov. George W. Bush in the Republican primary. Mr. McCain scored a surprising showing in New Hampshire but was unable to overcome the inevitability of a second Bush in the White House.

Eight years later, Mr. McCain tried again, emerging as the early favorite on the Republican side for a country that had wearied of Mr. Bush. Again, Mr. McCain stumbled early, overspending and struggling in the polls.

He cut back his staff so much that he famously began to carry his own bags on the campaign trail. The bare-bones approach fit him well, and he easily surmounted Mitt Romney to claim the party’s nomination.

Any other year he would have been formidable in a general election — but eight years of Mr. Bush and the enticing opportunity for voters to elect the first black president, in Democratic nominee Barack Obama, were again too much for him to surmount.

Mr. McCain responded to the losses with characteristic self-deprecating humor.

“I’ve been sleeping like a baby,” he told late-night show host Jay Leno after his 2008 defeat. “Sleep two hours, wake up and cry, sleep two hours, wake up and cry.”

Bipartisan pushes

Mr. McCain survived scandals that doomed his colleagues, emerging scarred but no less powerful in the corridors of Congress, nor less beloved by the press.

When he did penance, the country did it along with him.

That was the case after he was snared in the Keating Five, a handful of senators accused of flexing their influence to try to head off a federal investigation of a wealthy Phoenix businessman. After reprimands and admonishments by the Senate ethics committee in 1991, most of the senators announced retirements.

Mr. McCain was chastened but turned the episode into a defining political moment. He began to rail against the system he blamed for allowing corruption into Congress, resulting in the 2002 Bipartisan Campaign Reform Act, better known as McCain-Feingold, which he co-sponsored with Sen. Russell Feingold, Wisconsin Democrat.

The law was controversial from the beginning — indeed, even as he signed the bill Mr. Bush said parts of it were unconstitutional.

Mr. McConnell led the push against his fellow Republican senator, even taking the matter to the Supreme Court. Mr. McCain’s law prevailed in the first go-around in 2003, but by 2010 the high court had whittled it down, leaving the chaotic, interest-group-dominated system that prevails today.

Mr. McConnell said he and Mr. McCain spent a decade in that fight and then worked to rebuild their relationship: “You’d rather be on his side than not,” the Kentucky Republican concluded.

Mr. McCain also teamed up with Sen. Edward M. Kennedy, Massachusetts Democrat, in 2006 to write a massive immigration overhaul bill. McCain-Kennedy became the blueprint for every comprehensive immigration bill since, even though Mr. McCain wasn’t always on board. He said at times that the country needed more border security first.

Mr. McCain and Mr. Kennedy came to symbolize the era of Big Legislators — senators who struck deals, made compromises and then built their own coalitions, even if it meant going around party leaders.

Yet Mr. McCain also wasn’t bound by past stances, including on immigration, where he would take a stiffer stance toward the illegal side of the equation in his 2008 presidential campaign, only to emerge a legalization support after his loss.

One area on which Mr. McCain had no such wobbles was pro-life issues. The movement counted him among its best supporters.

He was also wary of Russia and warned Americans to be cautious of Mr. Putin early on. After Mr. Bush said he saw in the Russian leader’s eyes the look of a man who could do business, Mr. McCain retorted that when he looked at Mr. Putin, “I saw three letters: K-G-B.”

The inability to pigeonhole Mr. McCain has often confounded voters, and he is more beloved among Democrats than in his own party. That is particularly true in Arizona, where a CBS News poll in June found 62 percent of Democrats had a favorable view of him, compared with 20 percent of Republicans.

• Stephen Dinan can be reached at sdinan@washingtontimes.com.

Please read our comment policy before commenting.