The Democratic Republic of the Congo is half a world away, but stopping the Ebola outbreak that’s claimed nearly 60 people in the African nation is still an integral part of President Trump’s goal of “putting America first,” the nation’s top disease fighter said Wednesday.

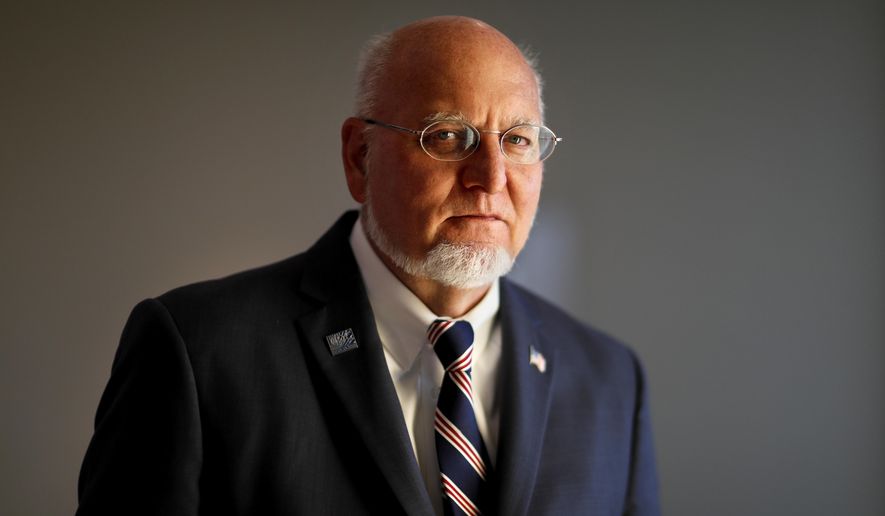

Dr. Robert R. Redfield, director of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, just returned from a visit and said U.S. efforts there are critical to stopping spread of the disease that terrorized the globe just a few years ago, during a previous outbreak in West Africa.

“I would argue it’s a really critical component of, if you will, putting America first in making sure that we can identify, detect and prevent global health threats that could negatively impact the state and well-being of Americans,” Dr. Redfield told The Washington Times.

The virus is infecting health workers and exacting an ever-larger death toll in a province riven by armed conflict, and public health officials fear the conditions are right for it to spread to neighboring countries.

Dr. Redfield said the CDC is embedding an employee inside the DRC’s health ministry to keep abreast, and nearly 30 CDC employees are coordinating the response from Beni, at the heart of the outbreak, to Kinshasa, the nation’s capital, to Geneva, Switzerland, which is home to the World Health Organization.

The agency’s also trained 30 Congolese to track down local contacts of infected persons through its field epidemiology program.

Dr. Redfield faces a series of domestic challenges, from opioid-fueled overdose deaths to food-borne disease outbreaks, yet he views global health security as one of his leading priorities.

“The truth is, part of our mission to protect the health and well-being of America is to identify and curtail these epidemics and [their] potential where they are. Stop them where they are,” he said. “Some people try to demarcate international versus domestic. I think we kind of passed over that somewhere in the early ’80s, where we became global. I don’t know if a lot of us recognized it, but it happened.”

Influenza strains from China and microbial that develop resistance to antibiotics in India can swiftly become a problem for Americans.

And recent global scares like mosquito-borne Zika virus, which has been linked to birth defects, and Ebola, an often-fatal illness that spreads from human to human through the bodily fluids of people with symptoms, have grabbed headlines.

An Ebola outbreak in another part of the DRC was quickly stamped out earlier this year, yet the new outbreak — in North Kivu province — is already more deadly and threatens borders with Uganda and Rwanda.

Dr. Redfield said his weeklong trip was to size up the situation personally.

“It’s better to over-respond at the beginning and then pull back,” he said. “The reason I went is just to make sure, ’Are we giving all the support that needs to be done at this moment in time?’”

He said the availability of a trial vaccine, supplied by Merck, seemed to help responders in identifying contacts of those who are infected.

More than 2,100 people have received a trial vaccine, and thousands of additional doses are on their way, he said.

“Sometimes, contacts didn’t really want to be identified,” he said. “Now that you know that if you’re a contact, that you can maybe get a vaccine that will prevent you from getting sick, maybe contacts want to be identified.”

So far, the World Health Organization been able to follow up with known contacts, or they’re working with health workers within difficult zones to access them.

The center of the outbreak is in Mangina, a secure and accessible area, though there are surrounding areas that are difficult to reach due to active conflict in the region between government and rebel militia factions.

“No cases have been identified in hard-to-reach areas,” said WHO spokesman Tarik Jasarevic.

As of Monday, the outbreak had been linked to 102 confirmed or probable cases and 59 deaths.

The director said the next seven to 10 days could determine the arc of the outbreak, as they monitor and treat identified patients and see whether the incubation period for Ebola — 21 days — begins to lapse without new groups of infections cropping up.

In the meantime, the CDC will keep helping the DRC wherever it can.

“We know how to do this,” Dr. Redfield said. “This is what we do for a living.”

• Tom Howell Jr. can be reached at thowell@washingtontimes.com.

Please read our comment policy before commenting.