The Ron Paul Revolution has lost much of its political force.

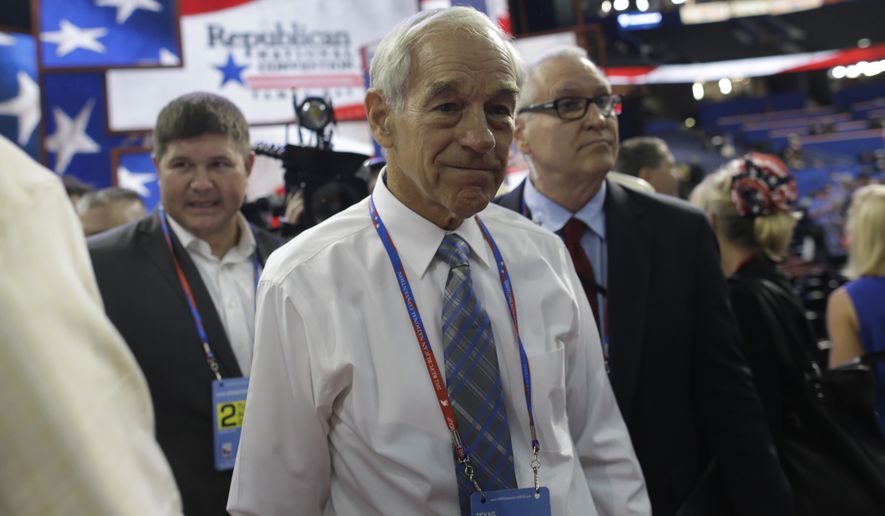

A little over a decade ago, Mr. Paul, a congressman and Republican presidential candidate, was a 2008 campaign-season sensation, drawing tens of thousands of followers, some decked in Colonial-era tricorn hats and/or Guy Fawkes masks, eager to hear their hero explain the gold standard and decry U.S. monetary and foreign policy.

Although his 2008 and 2012 presidential runs didn’t make much of a mark on the election, they did threaten to upend the Republican Party, with Paul acolytes grabbing control of state parties and sparking major rules changes, and demanding that the party adopt his libertarian-infused ideas.

But somewhere along the way, the revolution ran aground.

Though Mr. Paul and his son, Sen. Rand Paul, Kentucky Republican, remain active in politics, the movement they spawned is a shell of what it once was, torn asunder by the twin forces of Donald Trump on the one hand, and frustration on the other.

“Those Ron Paulers who stuck around — we are still trying to work within the system to right the ship of state, to expose the deep state, those political bureaucrats that have kind of captured our government. No matter who is elected, they seem to retain control,” said Carl Bunce, who led Nevada operations for the senior Mr. Paul and is now chairman of the Clark County Republican Party. “That is what we were fighting from the very beginning.”

Yet Mr. Bunce figures only about one-quarter of the people Mr. Paul counted as followers are still engaged. The rest, he said, are so disgusted with politics that they “probably hate that they ever got involved.”

“Some are living in the middle of the wilderness. … They’ve just checked out completely,” he said.

Mr. Paul made his mark in Congress as “Dr. No,” famous for voting against nearly every bill to spend taxpayers’ money. Representing Texas, he also opposed the Iraq War, voted against the Patriot Act, demanded an end to the federal war on drugs — and, of course, delivered withering critiques of American monetary policy.

He mounted his first presidential campaign as the nominee of the Libertarian Party in 1988, winning about 0.5 percent of the vote. But the rise of internet politicking gave him a broader reach and a chance to organize, and his 2008 campaign set fundraising records and drew new blood into politics.

Those newcomers helped shape Mr. Paul as much as he shaped them — including devising the concept of the “moneybomb,” a one-day online fundraising blitz, and pioneering new methods of outside spending to back a candidate.

But as innovative as his campaigns were, they achieved only moderate success at the polls. He came in fourth in the number of votes among Republican primary contenders in 2008 and did the same in 2012.

His impact, though, was felt far beyond those numbers.

His supporters launched takeovers of some state parties and forced rules changes at the national level, as leaders tried to fend off future insurgencies.

Mr. Paul’s followers say some of the libertarian ideas he championed have become mainstream in the past decade — and not just in politics.

“Uber and Air B&B, the decentralization of products and services, the whole ’Live and Let Live’ credo I think is flourishing today,” said David Fischer, the Iowa co-chair for Mr. Paul’s 2008 and 2012 campaigns. “Look at what is happening with cannabis. … Look at the growth of home-schooling and how it has gone mainstream.”

Yet many of the political issues Mr. Paul thrust into the national discussion have also faltered.

Mr. Paul’s demand for deep spending cuts and a full audit of the Federal Reserve System have stalled on Capitol Hill, and his calls for lawmakers to put the Constitution front and center in congressional debates have fallen by the wayside.

His supporters say the Paulist philosophy is still resonating outside of Washington — particularly with younger generations.

“It remains true that the biggest single gateway drug to libertarianism over the past 10 to 12 years has been Ron Paul,” said Matt Welch, editor-at-large of the libertarian magazine Reason. “No one thought you could run anti-interventionist or anti-war politics in the Republican Party and succeed, and Ron Paul demonstrated that at least it could be a topic that could galvanize people.”

Mr. Welch pointed to the *Young Americans for Liberty, which grew out of Mr. Paul’s 2008 campaign, and Students for Liberty as examples of groups that have flourished.

But the Republican Party has trended away from libertarian ideas, particularly in the past few years as Mr. Trump has captured leadership of the party.

“In spite of what some people thought of Ron Paul’s campaigns, it was a movement of ideas. It was not about Ron Paul the individual; it was about the message of freedom, prosperity and peace,” Mr. Fischer said. “Sometimes I think the Trump phenomenon is more personality-based, and I get that given the enormity of Trump’s personality. I feel like ours was more cerebral and issues-based rather than personality-based.”

Mr. Welch said it comes down to priorities: “The people that were going to Ron Paul rallies in 2007 and 2008, those people were not mad necessarily about NFL players kneeling for the national anthem.”

Still, that’s not to say Paul backers don’t find any common ground with the president or that none of them is committed to Mr. Trump.

They applaud him for pulling out of the Paris agreement on climate change, pushing for peace on the Korean Peninsula and bucking the political establishment to try to get along with Russia. They celebrate his tax cuts, push for criminal justice reform and deregulation efforts.

On the other hand, some say they are not thrilled about his lying. Some question his commitment to curbing the surveillance state and reducing the national debt. Some opposed his airstrikes in Syria and say his approach to economic policies has been scattershot.

“His solutions are not necessarily the solutions we need,” said A.J. Spiker, vice chairman of Mr. Paul’s 2012 Iowa campaign who has since returned to his real estate business. “We really need more free markets and open markets. As much as tariffs may excite the working class, at the end the day they are the ones that are paying for tariffs. I think that gets lost on people.”

Others have been taken aback by how willing some Paul supporters have been to embrace Mr. Trump wholesale.

“Ron Paul, if he taught us one thing, it was right from wrong and not partisanship,” said Jane Aitken, co-founder the New Hampshire Tea Party Coalition and taxpayer advocate. “I am finding that people have forgotten that they are all of a sudden very partisan.”

“We saw it with the Obamabots; we are seeing it with Trump now,” she said. “People put all their eggs in one basket with one person. It goes against common sense.”

She has become jaded when it comes to national politics and has decided she can do more at the state and local levels.

Drew Ivers, a longtime political hand who ran presidential campaigns in Iowa for Pat Robertson in 1988 and Pat Buchanan in 1996, before running Mr. Paul’s 2008 and 2012 operations, said he is done with it all.

“I retired politically after the 2014 cycle and did not engage in the 2016 cycle and plan not to engage in this 2018 cycle,” Mr. Ivers said in an email. “The globalist/nationalist battle is much more transparent than it has been over the past few decades and is manifested more and more politically and overtly as the true war it is.”

Mr. Bunce said the Ron Paul movement has evolved over the past decade.

’We thought we can elect this one guy and everything will get fixed,” he said. “It was naive, but again we were very young and new to the process. … Believe me, it was a fun ride thinking we could change the world in one political cycle.

“If we got Ron Paul elected, would he do what Donald Trump did? Maybe not,” Mr. Bunce said. “Maybe Donald Trump is the guy who can break up the deep state so someone like Ron or Rand can get in and legislate to make the changes we want.

“After all,” he said, “to make changes you have to cut the dragon’s head off.”

* (Correction: A previous version of the story incorrectly identified the name of a group. The correct name is the Young Americans for Liberty. The story has been updated.)

• Seth McLaughlin can be reached at smclaughlin@washingtontimes.com.

Please read our comment policy before commenting.