OPINION:

Critics know what’s wrong with the European Union. It suffers from what they call a “democratic deficit.” Democracy is often loud, usually messy and everyone gets a voice. This is inconvenient for the elites and the bureaucrats.

The unelected Eurocrats embrace all the politically correct positions on climate change, capital punishment, immigration and genetically modified foods, but they know in their hearts they’re acting against the hopes and wishes of many ordinary Europeans. The Eurocrats in Brussels issue regulations, overrule local taxing officials and pass judgment on member states’ fidelity to classic-liberal political ideals. Bureaucrats in Europe, like those here, never have to face a voter.

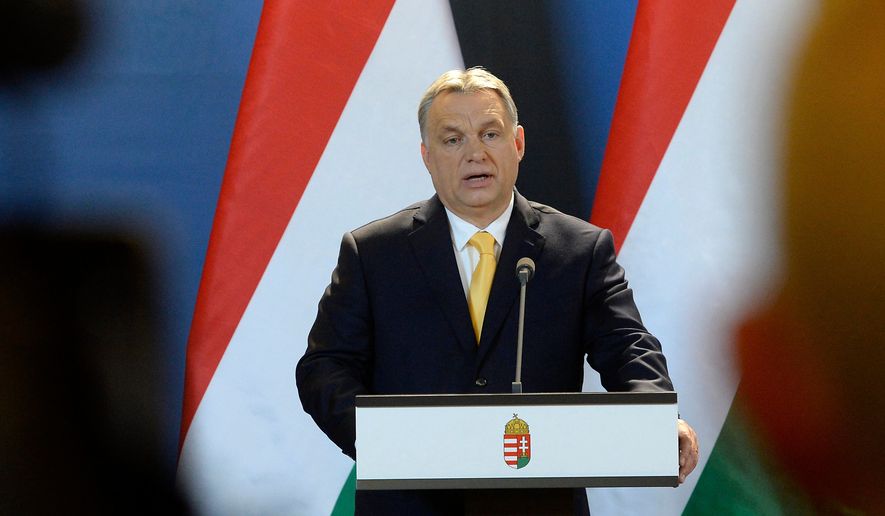

This disease at the heart of the European project is getting a fresh look in the stand-off between the powers-that-be in Brussels and the popular government in Hungary. Prime Minister Viktor Orban, an immigration skeptic whom the European left loves to hate, won a remarkable victory in the parliamentary elections April 8, winning a third four-year term. His governing Fidesz Party and the allied Christian Democratic People’s Party won just under 50 percent of the vote and 134 seats in the 199-seat parliament. Left-leaning parties won only 38 seats.

Mr. Orban, 54, is no Boy Scout. Once considered the face of the wave of Eastern European democratic leaders which has emerged in the wake of the collapse of the Soviet Union, he has taken a tough line on critics at home and abroad, notably in his feud with George Soros, the left-wing billionaire Hungarian-American financier who pokes his finger in politics in a lot of unlikely places, including the United States.

To the consternation of his critics, Mr. Orban refuses to toe the line laid down by the bureaucrats in Brussels on immigration. He argues that the flood of unchecked migrants poses both a security and a cultural problem for Hungary. He is accused of peddling prejudice against Islam because he appeals to the traditional Christian values echoed across the region.

Anyone listening to Mr. Orban’s critics will detect an echo of the elitist response to President Trump’s improbable electoral success here. A blogger on Foreign Policy.com warns that the “coming years will show how much democratic backsliding is possible in a country that is a member of the European Union.” The Civil Liberties, Justice and Home Affairs Committee of the toothless European Parliament is pushing now to strip Hungary of its voting rights in the European Council because Mr. Orban’s electoral triumph has undermined “the fundamental rights of its citizens.”

The British daily Guardian headlined an account the day before the April 8 vote “Hungary’s war on democracy is a war on democracy everywhere.”

What the critics can’t see is that, whatever else Mr. Orban’s victory was, it was not undemocratic. There were the usual cavils about press favoritism and the advantages of incumbency, but Mr. Orban and his allies won because they got the most votes. That’s how elections work, which losers there, like here, have trouble understanding. Populism, particularly conservative populism that doesn’t mock voters’ long-held beliefs and values, turns out to be popular with most voters.

Mr. Orban’s ideas on immigration and other issues may be “retrograde” to what is becoming the losing class, but his government has the Hungarian economy humming, foreign investment booming, and wages rising. Hungarians, despite the hyperventilating in the salons of Western Europe, were hardly tricked into voting for a government that has a record of eight years in power on which to be judged. Some former skeptics concede that Mr. Orban and other regional leaders such as Polish Prime Minister Mateusz Morwiecki offer a model for how a country can be a contributing member of the EU, NATO and the broader fraternity of liberal democracies without losing its distinctive identity.

Jens Spahn, the German health minister regarded as a possible successor to Chancellor Angela Merkel, favorably compares Mr. Orban’s stance to that of Angela Merkel, who was badly burned in 2015 by her experiment with wide-open borders. “There’s much criticism of Viktor Orban, but he imposes European law on the border and secures Europe’s border,” Mr. Spahn recently told a Swiss newspaper.

If there’s a short-circuiting of democracy in Europe, it’s in Brussels, not Budapest. The leaders of the European Union could take a page from Mr. Orban’s playbook and actually listen to the people they claim to represent. If they continue to send Olympian diktats from on high, they must be prepared to see proud countries like Hungary following the British to the exits.

Please read our comment policy before commenting.