OPINION:

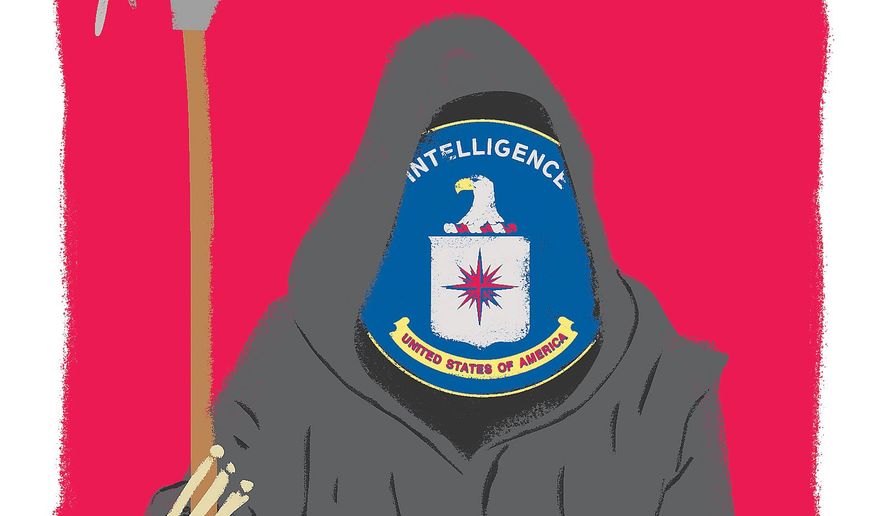

The Central Intelligence Agency’s authority to use lethal force is usually discussed only in the quietest corners of the intelligence community. These authorities are usually implemented pursuant to carefully-prescribed top-secret “presidential determinations” that authorize specific actions.

Over its history, the CIA’s successes in using lethal force are unknown to the public. We only know the times when the CIA tried to use it — such as the much-mocked attempts in the 1960s to kill Fidel Castro — and was embarrassed by public failures. In 1984, President Reagan, in Executive Order 12333, prohibited our intelligence agencies from planning or participating in political assassinations.

Reports that CIA Director Mike Pompeo is pushing for wider authority to use drone strikes in active war zones including — but, importantly, not limited to — Afghanistan has ignited a public debate. President Trump reportedly favors granting Mr. Pompeo’s request and the Pentagon apparently is divided in its position. Advisors to former President Obama are, predictably, against it.

One New York Times report quotes Luke Hartig, a National Security Council official in the Obama administration, who said that transparency in discussing military operations such as drone strikes with allies was of utmost importance. That report quoted Mr. Hartig as saying any decrease in transparency would be. ” a big strategic and moral mistake.”

Let’s set aside, for the moment, the fact that Mr. Obama’s Afghanistan policy failed utterly. What we cannot set aside is the fact that one of the reasons — if not the main reason — that the 2011 SEAL mission to kill or capture Osama bin Laden succeeded was that it was kept secret from both the Pakistanis and the Afghanis until it was almost over.

Secrecy, not transparency, is the sine qua non of military and intelligence operations. Transparency is essential in dealing with reliable allies such as some of the NATO nations and Israel, but it has proved both counter-productive, and sometimes deadly, to our forces in dealing with governments such as Afghanistan’s and Pakistan’s.

John Brennan, when he became CIA director in 2013, significantly cut back the CIA’s paramilitary operations. Among them were the CIA’s operations of killer drones. Mr. Pompeo apparently wants to return the CIA’s operations to the pre-Brennan era and perhaps go farther.

Strategically, what Mr. Pompeo is proposing theoretically could enable the CIA to successfully target people such as Taliban leaders and the leaders of the Haqqani network, a tribal-based terror group that is part of the Taliban. The latter is the most deadly threat to us in parts of Afghanistan. Beheading those snakes won’t completely end the threats they pose, but they will necessarily result in slowing, or stopping entirely (but temporarily) their operations against us and our NATO partners in Afghanistan.

Defense Secretary Mattis reportedly hasn’t objected to Mr. Pompeo’s idea, but others reportedly worry — correctly — that our troops (and NATO’s) will bear the brunt of any counterattacks. Part of those objections is the military’s normal reluctance to let anyone else have a finger on the trigger.

For nearly 16 years, the military and the CIA have worked together in Afghanistan, Iraq and elsewhere. That partnership has produced some good results, such as the death of bin Laden, but that may be the exception to the rule.

Our war efforts in Afghanistan and Iraq (and elsewhere) have suffered from many things ranging from Mr. Bush’s ill-advised nation-building strategy to Mr. Obama’s unreasonably restrictive rules of engagement and — as Mr. Hartig implied — placing greater importance on political appearances such as “transparency” than progress toward victory.

The question of granting the CIA’s desire for greater authority to act on its own in Afghanistan, Iraq and elsewhere boils down, like so many questions of tactics and strategy, to balancing risk against reward.

The most important variable in that equation, like almost everything else in this war, is the ability to gather actionable intelligence which both the CIA and the military do.

If the CIA could gather, analyze and apply intelligence to operational forces better and faster than the military can, the CIA could target and kill them as fast or faster than the military can.

The CIA and the military, at least supposedly, cooperate and share intelligence. But both are bureaucracies with their own hierarchies. Such entities don’t naturally cooperate.

If the president grants the CIA’s request he will have, intentionally or otherwise, created a competition between the military and the CIA. That could be good in the short run, each side wanting to try harder to get the credit. In the longer term it will certainly be a very bad idea, causing each to conceal what intelligence they have from the other. That will save many terrorists’ lives.

It would be far better for the president to prevent that competition from arising by introducing “jointness” into the intelligence community.

“Jointness” — an awkward word even by Pentagon standards — means forcing cooperation among agencies by requiring assignment of people to each other’s agencies to train and operate with them. Though successes such as the bin Laden raid resulted from cooperation among agencies, requiring real jointness between the military and intelligence communities will break down the kind of barriers that Mr. Pompeo’s idea will create. It will kill more terrorists in less time than anything else the president can mandate.

• Jed Babbin, a deputy undersecretary of defense in the George H.W. Bush administration, is the author of “In the Words of Our Enemies.”

Please read our comment policy before commenting.