OPINION:

As a Vietnam veteran, I was reluctant to push the Ken Burns Vietnam documentary film button. Would it be little more than painful propaganda? This apprehension was only half right. It’s not propaganda. Every American should see it.

Of course, Mr. Burns can’t tell us everything and the picture he presents, however sharply and excruciatingly lucid, is in one aspect out of focus and incomplete, not by what he shows, but what he doesn’t.

Increasingly apprehensive about the success of the South Vietnamese regime of President Ngo Dinh Diem and his brother, Ngo Dinh Nhu, of the secret police, the Communists (VC/NVA) initiated a vicious guerrilla war against it, and by the summer of 1963 it seemed doomed.

Yet there was another option in the person of Mieczyslaw Maneli, Polish delegate to the International Control Commission. The ICC, India, Canada and Poland, monitored the Geneva Accords ending the French war.

Maneli was a resistance fighter in World War II. Interned in Auschwitz in 1943, he escaped in early 1945; post-war he taught law until assigned to the ICC.

Arriving in Saigon in early 1963, Maneli, along with his Indian counterpart, Ramchundur Goburdhun, had established a back channel between Saigon and Hanoi.

They had help. John Kenneth Galbraith, America’s ambassador to India, in “despair” about Vietnam, supported by India’s Prime Minister, Jawaharlal Nehru, formulated a peace initiative. This called for neutralization of South Vietnam — a cease-fire and a coalition government. Galbraith recalled that Kennedy said “to pursue the subject immediately.”

Maneli and Goburdhun picked up the Galbraith baton. Goburdhun conferred with Diem and then Maneli visited Hanoi in March. Encouraged, Maneli made several trips from Saigon to Hanoi.

On April 1 Galbraith met with JFK urging his peace proposal, but Averell Harriman, under secretary of State, and the Joint Chiefs resisted. Nevertheless Kennedy admonished, “to be prepared to seize upon any favorable moment to reduce our commitment,” even though it “might yet be some time away.”

Later Kennedy replaced Ambassador Frederick Nolting, opposed to removing Diem, with Henry Cabot Lodge, a hard liner favoring a coup, who arrived on August 22. Then, two days later, Kennedy authorized the infamous “August 24 Cable” to Lodge, demanding the removal of Nhu and threatening “the possibility that Diem himself cannot be preserved,” if he did not cooperate.

Maneli then met with Nhu publicly on August 25 and clandestinely on September 2. The latter, discovered by the CIA, was reported to Lodge. Rumors flew in Saigon about a “secret deal” between Diem-Nhu and Ho Chi Minh.

Alarmed, on September 13, Lodge cabled Secretary of State Dean Rusk asking “what our response should be if Nhu, in the course of a negotiation with North Vietnam, should ask the U.S. to leave South Vietnam or to make a major reduction in forces?”

On September 16, Nhu met with South Vietnamese generals (ARVN) revealing the Maneli back channel, emphasizing that the North was interested in trade, and that Maneli was “ready to fly to Hanoi at a moment’s notice.”

Then on September 18, Joseph Alsop, a hawkish American journalist visiting Saigon, published an article titled “Very Ugly Stuff” in The Washington Post disclosing the Maneli negotiations. A blaze became a firestorm.

Kennedy’s “favorable moment” had arrived and he had just been handed the key to an unopened door. The crises of 1963 and the Galbraith initiative offered both the rationale and means of exiting Vietnam. But would he use it?

Instead, JFK dithered: on September 21, he sent Robert McNamara and Maxwell Taylor to Saigon. On October 2, they reported the war could be won by late 1965, with new leadership. No adviser in the field bought it, but Kennedy bought the hope of it. He bought that hope because he wanted to buy it; because he, like LBJ after him, wanted reelection in 1964, and neither wished it charged that they had “lost Indo-China.”

He authorized the coup of November 1. Diem and Nhu were executed as an ARVN general pronounced them “traitors” for negotiating with Hanoi. However, following the fall of a despot, the first day is frequently the best.

President Kennedy was assassinated, and the U.S. was set in an upward spiral of mismanaged military half measures resulting in the climacteric of April 30, 1975, when it all collapsed.

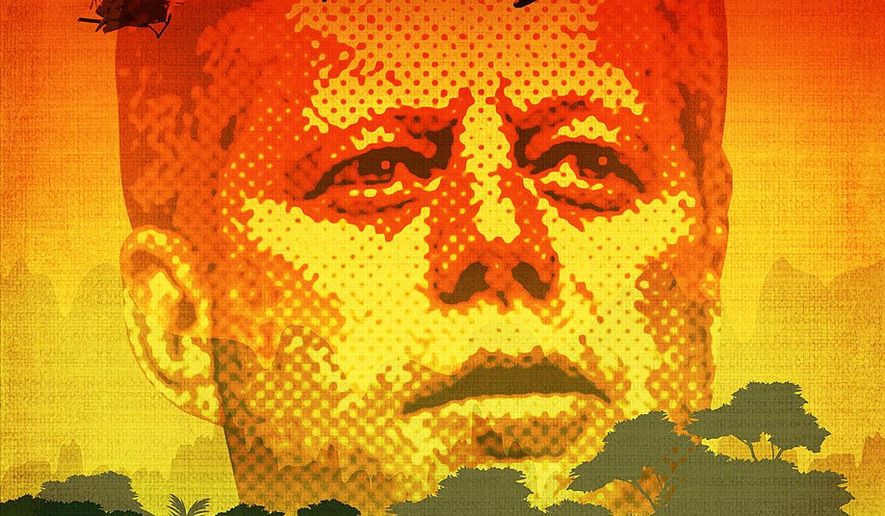

After almost 12 more years of war, with 58,318 American, 250,000 ARVN, 1,000,000 VC/NVA, and at least as many civilian deaths, we see America in the last helicopter finally passing through that exit door in abject defeat. Ken Burns shows us that cataclysm almost too well, but riding in that chopper was the one worthy thing America would ever salvage from Vietnam, the heroism and sacrifice of those it sent.

• Phillip McMath, the son of a former Democratic governor of Arkansas, is a lawyer in Little Rock.

Please read our comment policy before commenting.