OPINION:

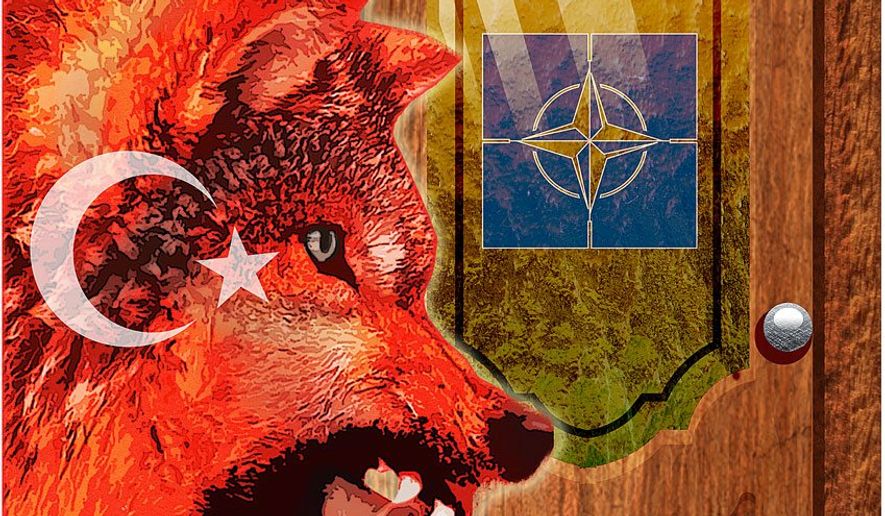

The North Atlantic Treaty Organization, known as NATO, faces an existential problem.

No, it’s not about getting member states to fulfill agreed-upon spending levels on defense. Or finding a role after the Soviet collapse. Or standing up to Russia’s Vladimir Putin. Rather, it’s about Recep Tayyip Erdogan, the Islamist, dictatorial ruler of Turkey whose policies threaten to undermine this unique alliance of 29 states that has lasted nearly 70 years.

Created in 1949, NATO’s founding principles ambitiously set out the alliance goal “to safeguard the freedom, common heritage and civilization of [member states’] peoples, founded on the principles of democracy, individual liberty and the rule of law.” In other words, the alliance exists to defend Western civilization.

For its first 42 years, until the USSR collapsed in 1991, this meant containing and defeating the Warsaw Pact. Today, it means containing and defeating Russia and Islamism. Of these latter two, Islamism is the deeper and longer-lasting threat, being based not on a single leader’s personality but on a highly potent ideology, one that effectively succeeded fascism and communism as the great radical utopian challenge to the West.

Some major figures in NATO appreciated this shift soon after the Soviet collapse. Already in 1995, Secretary-General Willy Claes noted with prescience that “Fundamentalism is at least as dangerous as communism was.” With the Cold War over, he said, “Islamic militancy has emerged as perhaps the single gravest threat to the NATO alliance and to Western security.”

In 2004, Jose Maria Aznar, Spain’s former prime minister, warned that “Islamist terrorism is a new shared threat of a global nature that places the very existence of NATO’s members at risk.” He advocated that NATO focus on combating “Islamic jihadism and the proliferation of weapons of mass destruction” and called for “placing the war against Islamic jihadism at the center of the allied strategy.”

But, instead of a robust NATO on the Claes-Aznar model leading the battle against Islamism, it was internally hobbled by Mr. Erdogan’s opposition. Rather than assert the fight against Islamism, the other 28 members dismayingly deferred to the Islamist within their ranks.

The 28 stay mum about the near-civil war the Turkish regime wages in southeastern Anatolia against its own Kurdish citizens. The emergence of a private army (called SADAT) under Mr. Erdogan’s exclusive control seems not to bother them.

Likewise, they appear oblivious to Ankara’s unpredictably limiting access to the NATO base at Incirlik, the obstructed relations with friendly states such as Austria, Cyprus and Israel, and the vicious anti-Americanism symbolized by the mayor of Ankara hoping for more storm damage to be inflicted on the United States.

Maltreatment of NATO-member state nationals hardly bothers the NATO worthies: Not the arrest of 12 Germans (such as Deniz Yucel and Peter Steudtner) nor the attempted assassination of Turks in Germany (such as Yuksel Koc), not the seizure of Americans in Turkey as hostages (such as Andrew Brunson and Serkan Golge), nor repeated physical violence against Americans in the United States (such as at the Brookings Institute and at Sheridan Circle).

NATO seems unfazed that Ankara helps Iran’s nuclear program, develops an Iranian oil field, and transfers Iranian arms to Hezbollah. Mr. Erdogan’s talk of joining the Moscow-Beijing dominated Shanghai Cooperation Organization ruffles few feathers, as do joint exercises with the Russian and Chinese militaries. A Turkish purchase of a Russian missile defense system, the S-400, appears to be more an irritant than a deal-breaker. A mutual U.S.-Turkish ban on visas fazed no one.

NATO faces a choice. It can, hoping that Mr. Erdogan is no more than a colicky episode and Turkey will return to the West, continue with the present policy. Or it can deem NATO’s utility too important to sacrifice to this speculative possibility, and take assertive steps to freeze the Republic of Turkey out of NATO activities until it again behaves like an ally. Those steps might include:

• Removing nuclear weapons from Incirlik.

• Closing NATO’s operations at Incirlik.

• Canceling arms sales, such as the F-35 aircraft.

• Exclude Turkish participation from weapons development.

• Refuse to share intelligence.

• Refuse to train Turkish soldiers or sailors.

• Reject Turkish personnel for NATO positions.

A unified stance against Mr. Erdogan’s hostile dictatorship permits the grand NATO alliance to rediscover its noble purpose “to safeguard the freedom, common heritage and civilization” of its peoples. By confronting Islamism, NATO will again take up the mantle it has of late let down, nothing less than defending Western civilization.

• Daniel Pipes is president of the Middle East Forum.

Please read our comment policy before commenting.