Federal law enforcement seized roughly 7,500 cellphones and other mobile devices during the last year incapable of being examined for possible criminal evidence, Deputy Attorney General Rod Rosenstein said Tuesday, quantifying the cost of tech companies manufacturing increasingly secure but supposedly “warrant-proof” smartphones.

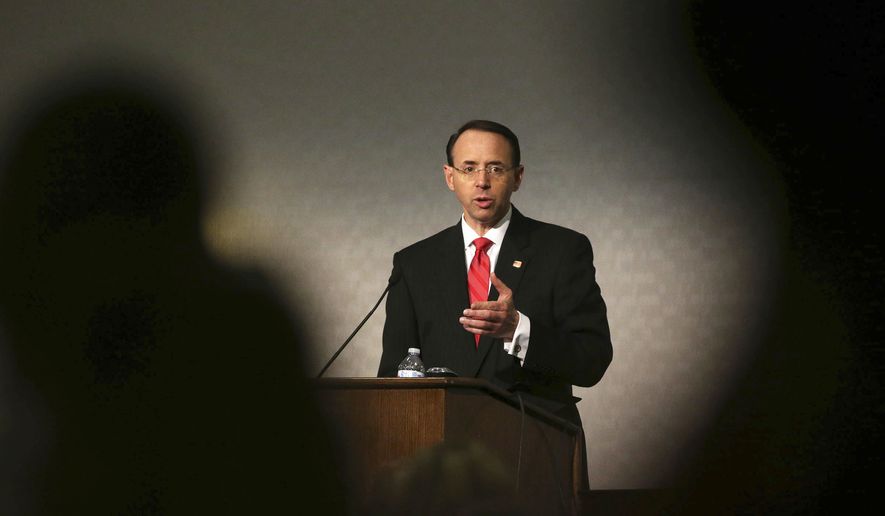

Mr. Rosenstein mentioned the previously unpublicized statistic while reiterating his concerns with criminal suspects using increasingly ubiqutous technology including robust encryption and password-protected devices to obfuscate their digital communications from authorities — a phenomenon the FBI commonly refers to as “Going Dark” — during an address at the U.S. Naval Academy in Annapolis, Maryland, according to a copy of his prepared remarks released by the Justice Department.

“Today, thousands of seized devices sit in storage, impervious to search warrants,” Mr. Rosenstein said, according to the transcript. “Over the past year, the FBI was unable to access about 7,500 mobile devices submitted to its Computer Analysis and Response Team, even though there was legal authority to do so.”

“Police and prosecutors were the first to recognize the danger posed by the ’going dark’ trend, but the public bears the cost,” Mr. Rosenstein added, according to the transcript. “When investigations of violent criminal organizations come to a halt because we cannot access a phone, lives may be lost. When child molesters can operate anonymously over the internet, children may be exploited. When terrorists can communicate covertly without fear of detection, chaos may follow.”

While the FBI’s “Going Dark” dilemma has frustrated investigators for years, the bureau’s inability to access digital evidence worsened after Apple and Google, manufacturers of the nation’s most popular smartphones, introduced added security measures in 2014 making it difficult for authorities to glean data from seized devices.

The issue took center stage the following year after federal investigators recovered a password-protected iPhone from the scene of a mass shooting in San Bernardino, California, prompting a widely-reported legal battle between the Department of Justice and Apple that was eventually resolved out of court.

Nearly two years after the shooting, Mr. Rosenstein’s remarks suggests the FBI is encountering obstacles accessing smartphones more often than ever when compared to previous comments.

James B. Comey, the former director of the FBI ousted earlier this year by President Trump, testified in May that encryption prevented authorities from accessing digital evidence from about 46 percent of the roughly 3,000 smartphones and other electronic devices seized by criminal investigators during a preceding six-month span.

Mr. Rosenstein’s latest comments on encryption constitutes the second time in two weeks the deputy attorney general has publicly discussed encryption — last week he said that “warrant-proof” encryption has created a “serious problem” for law enforcement deserving of a “candid public debate.”

• Andrew Blake can be reached at ablake@washingtontimes.com.

Please read our comment policy before commenting.