Using a chicken bone for a quill and ink made of blood and rust from prison bars, prisoners in Syria’s secret jails scrawled 82 names on five pieces of cloth.

One prisoner, a tailor, sewed the cloth into a shirt to be worn by the first man released — to smuggle the names out and tell their families of their fate.

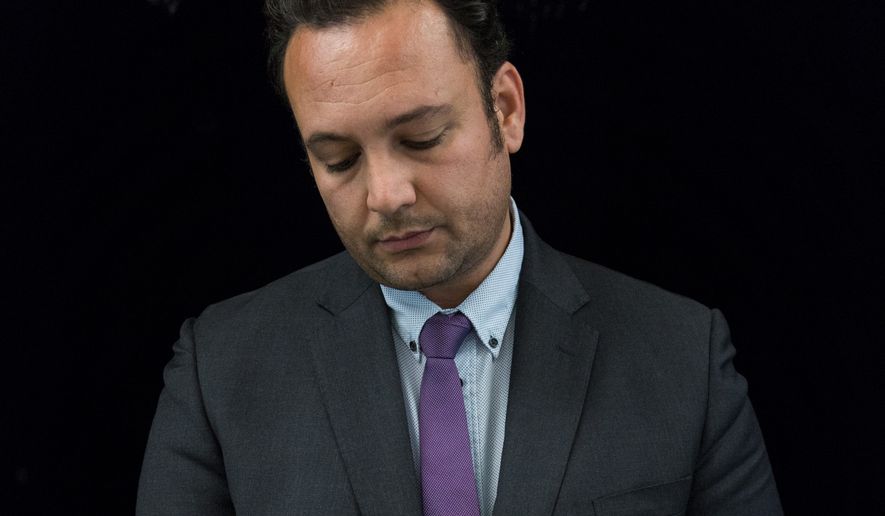

Those five pieces of cloth now are part of a new exhibit at the U.S. Holocaust Memorial Museum called “Please don’t forget us.” It tells the story of Mansour Omari (the smuggler), his fellow prisoners and the atrocities of the Syrian regime against its people.

“So now I can say, ’Now we have this exhibition. I somehow fulfilled the promise I made to them that we wouldn’t forget,’” Mr. Omari said Thursday at the museum. “Everyone who comes to the exhibition will bear witness.”

The exhibit is part of the museum’s ongoing mission to alert the world to crimes against humanity, said Cameron Hudson, director of the Simon-Skjodt Center for the Prevention of Genocide.

“We look at those cases where mass killings, mass atrocity, genocide are occurring in the world today, and I think there’s probably no better example of that than in Syria — maybe the worst example is Syria,” Mr. Hudson said. “How do you tell that story of such staggering numbers? You do it through the stories of individuals, and that’s what we’ve tried to do here today.”

The temporary exhibit spans two rooms in the Holocaust museum.

“When you come into the first room, we try to give an overview of what’s going on in Syria, how civilians are being threatened and this less known story about how people are being disappeared,” said exhibit curator Jill Savitt.

Two videos are presented — one introducing Mr. Omari and his story, the other relating the efforts of “Caeser,” the alias of a Syrian government defector who smuggled out 55,000 photos of tortured and murdered civilians and political prisoners.

“I have never in my life seen pictures of bodies that were subjected to such criminality, except when I saw the pictures of the victims of the Nazi regime,” Caeser is quoted as saying.

In the next room, visitors can view the five pieces of cloth Mr. Omari smuggled out — each in its own display case, the Arabic names faded and hard to make out.

The room is dark and shadowy to evoke the feeling of a crowded prison. The cases are separated by scrim partitions and each one features an interview with Mr. Omari discussing his journey.

“As you walk around the room, it’s not a linear narrative but you do get a sense of what these clothes represent — which are human beings,” Ms. Savitt said.

Since the outbreak of Syria’s civil war in 2011, more than 500,000 people have been killed, 11 million displaced and hundreds of thousands of civilians arrested, imprisoned, tortured and disappeared — their fate unknown.

“The government denies that it has all those detainees,” Mr. Omari said of the motivation for his work, “so I think it was very important to get the names and the information for the families that your sons are alive.”

Much of the attention on Syria in recent years has focused on the fight against the Islamic State, or ISIS, but as the terrorist group is expelled from the country, Mr. Omari said he hopes attention will turn to holding the regime of Syrian President Bashar Assad accountable.

“Assad is the ISIS for Syrians,” he said.

Before his arrest in 2012, Mr. Omari was working for the Syrian Center for Media and Freedom of Expression, documenting disappeared peoples. That February, his office was raided by Syrian air force intelligence.

He believes the only reason he’s alive today is that one of the employees was able to get free and alerted the international media.

“Our news that ’The Syrian Center was arrested,’ was on Al Jazeera, Al Arabiya — even a French official, he made a statement asking to release us. This, I think, saved our lives,” Mr. Omari said.

He was taken to a makeshift prison three floors beneath a converted military facility.

“Already it’s not prepared to keep people. It was so dark, we had only one faint light and they switched it off most of the time and we never saw the daylight. The whole period I spent there we had to wear blindfolds all the time, for nine months,” he said.

His fellow prisoners were a mix of Syrian society — university students, media activists, doctors. There was at least one heart surgeon and a radiologist, and others who were arbitrarily rounded up by regime forces during neighborhood raids.

For breakfast, they were given two or three olives and some bread. In the evening, a pitiful portion of rice or bulgar.

“It was not for human consumption,” Mr. Omari said, adding that the cells were dirty, and their clothes were soon tattered and destroyed.

His main motivation though was to continue documenting the names and identities of the disappeared. The prisoners were able to take a few scraps of cloth — five in total. Concerned about creating an ink that wouldn’t fade, one prisoner cut his gums and spit the blood into a bag. They mixed it with rust from the bars and scribbled the names with a chicken bone.

They recorded 82 names. A tailor then sewed the pieces into a shirt.

On the day Mr. Omari’s name was called to be released, he was given the shirt to wear. All the prisoners gathered around him to hug him and were crying, repeating to him, “Don’t forget us.”

Transferred to a civilian detention center with less security, Mr. Omari was able to buy a notebook into which he transferred the names on the cloths, which he preserved between the pages.

Released to his family in 2013, he spent six days in Syria before fleeing to Turkey. He spent a year there before receiving asylum in Sweden.

His story was part of a BBC documentary on Syrian detainees and caught the attention of the Holocaust museum, which planned a the exhibit to preserve the pieces of cloth.

The exhibit opens Tuesday for six months. Admission is free.

• Laura Kelly can be reached at lkelly@washingtontimes.com.

Please read our comment policy before commenting.