MIAMI — The hum of traffic and clanking, gaseous sounds of a front-end loader are the few noises to disturb the stillness around Sean Taylor’s grave in the middle of the summer. It’s hot, humid and clear in Woodlawn Park Cemetery South. A small group just out of earshot is going through a funeral, standing together and looking down, about 100 yards from Taylor’s plot.

A red “21” is engraved in the middle of a football on his headstone. It is one of three etched in black lines to represent his three levels in the sport. An illustration of Taylor upending a Dallas Cowboys player commands the middle. A pot filled with giant sunflowers sits off the left edge. A clear glass case with a bouquet of red flowers is on the right. Just two days after the Major League Baseball All-Star Game in Miami, a Washington Nationals hat sits atop the headstone.

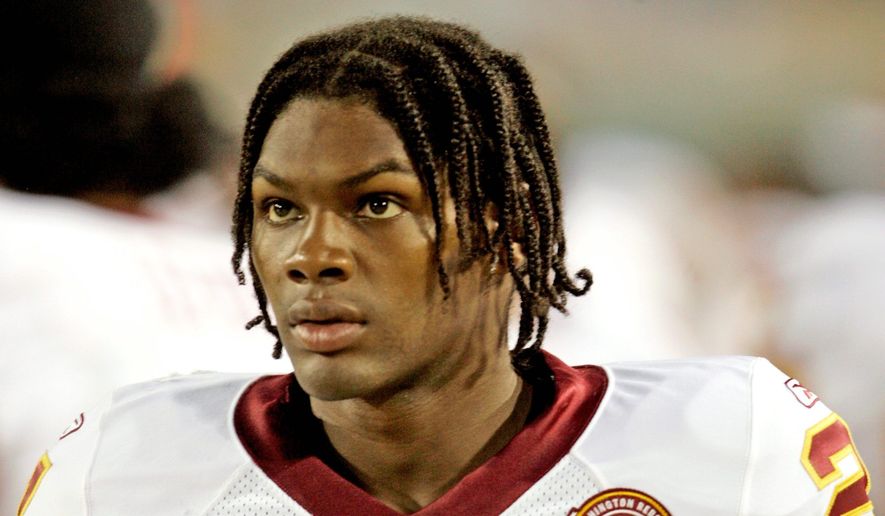

Taylor died 10 years ago Monday following a botched burglary attempt in his Palmetto Bay home. Greed prompted the break-in. Surprise that he was present led to tragedy.

In the decade since, Taylor’s legacy has flourished, anchored in nostalgia for what was and wonder of what could have been. His jersey is still worn by fans. Current players still revere him. The Redskins still miss him.

His then-infant daughter has grown to be a young woman who delivers speeches, his younger half-brother is a two-sport athlete at the same preparatory school he attended, his father remains in law enforcement and around the Redskins community.

The Internet has preserved his ferocity on the field. It’s easy to find footage of Taylor, a burgeoning 24 years old at the time of his death, hammering a punter in the Pro Bowl or a Florida State wide receiver during his halcyon days at the U. Combined, the highlight videos on YouTube have well over a million views. Two refer to Taylor as “God’s safety.” Various clips are dissected, discussed and absorbed by current safeties like Seattle’s Kam Chancellor and Washington’s D.J. Swearinger. Those two are trying to channel what Taylor had, what was taken from him, his family, the Redskins and the league. The videos help everyone remember, even if that hurts.

“You can’t be scared of death,” Taylor told ESPN 980 in September of 2007, just two months before the break-in. “When that time comes, it comes. … You never see a person who has lived their life to the fullest. They sometimes feel sorry for like a child, maybe, that didn’t get a chance to do some of the things they thought that child might have had a chance to do in life. I’ve been blessed. God’s looked out for me, so, I’m happy.”

***

The houses along Eureka Drive in southeast Miami become progressively nicer and larger as the Biscayne Bay Aquatic Preserve draws closer. An accurate sign marks the entrance to the green-filled area: “Welcome to Palmetto Bay, village of Parks.”

Take a left onto Old Cutler Road. A half mile up is Taylor’s former home, where he was robbed of his life by a ragtag band of five men who are now imprisoned in various facilities across Florida. The white wall and black fence out front of the four-bedroom, four-bathroom home are the same. The new owner purchased the property from a bank in 2011 for $460,000, almost half of the $900,00 Taylor paid in 2005. Just up the street is a library surrounded by parks. Nothing indicates this was or could be a place of violence.

Jailing the men who entered Taylor’s home Nov. 26, 2007, in search of money and expecting Taylor not to be there, was laborious, but is finally done.

Jason Mitchell will spend the rest of his life in Columbia Correctional Institution in Lake City. Venjah Hunte, who pleaded guilty to second-degree murder and burglary charges, was sentenced to 29 years in the Desoto Annex Correctional Facility in Arcadia. He can get out May 29, 2036. Charles Wardlow is serving a 30-year sentence in Martin Correctional Institute in Indiantown. Timmy Lee Brown, Wardlow’s cousin who was 16 at the time of the crime and has a teardrop tattoo on the corner of his left eye, received an 18-year sentence following a guilty plea. He can be released from Jackson Correctional Institute in Malone on Aug. 12, 2025, when he is 34 years old, the age Taylor would have turned in April of this year.

Eric Rivera’s trial lasted the longest because multiple attorney changes stalled his conviction for allegedly shooting Taylor. Two shots were fired. One struck Taylor’s femoral artery. Massive blood loss took Taylor’s life the next day. Rivera, who was 17 at the time, was not convicted until Nov. 4, 2013 and was found guilty of second-degree murder, not first, since the jury concluded he was not in the possession of a firearm at the time of the murder. He was sentenced Jan. 23, 2014, by then 23 years old and having removed his dreadlocks. Rivera was sentenced to 57 years and six months in Liberty Correctional Institute in Bristol. He is eligible for release Feb. 17, 2065, at which time the “laugh now” mask tattoo on his left arm and “cry later” mask tattoo on his right will be well faded.

“We have to live with this,” Pedro “Pete” Taylor, Sean’s father, said.

***

Under a small red tent to the left of the entrance at Redskins training camp in Richmond is a table stacked with books. Pedro Taylor takes a picture with a large fan in a Taylor jersey. Not far is another tent doubling as the Redskins’ merchandise store at training camp. Taylor’s jersey hangs between those belonging to Kirk Cousins and Josh Norman. It costs $155.

Person after person walked past books — and Pedro Taylor — until a guy in a Sean Taylor jersey takes a second look. He realizes this is somebody he thinks he recognizes. He wanders in, picks up a book, then begins to smile.

Progressively, more people start to come over instead of heading past the gate on Fan Appreciation Day, annually the most well-attended day of training camp in Richmond. Part of the crowd is drawn by shouts from the tent. “Meet Sean Taylor’s dad!”

“It’s a proud moment,” Pedro Taylor said of the ongoing fan interest. “It’s a sign of appreciation and it’s a sign of just carrying on that he represented the great Washington Redskins well.”

Sean Taylor’s ubiquitous jersey is part of his ongoing thread with the organization. Twice, he was named to the Pro Bowl, once posthumously, and even there he was leveling the opposition, memorably clobbering the AFC’s unexpecting punter, Brian Moorman, with a crunching blow in 2006.

Taylor should have been nearing the end of his playing career now, 34 years old and in his 14th season (if his body could handle his football style for that long). That could have resulted in 200 games, as opposed to the 55 that were enough to get him in the Redskins’ Ring of Fame.

Washington has not found another Pro-Bowl safety since Taylor was posthumously named to the game in 2007. In fact, finding stability at that position has been elusive as any.

LaRon Landry was moved to free safety in 2008 before splitting time at the safety spots the following season, moving back to strong safety and having his time in the Redskins’ back end dwindle. Kareem Moore’s chance in 2010 ended because of a knee injury. In 2011, it was O.J. Atogwe’s turn. He started eight games in what became his final NFL season. Madieu Williams was up in 2012. He started all 16 games, then never played again. Next was Brandon Meriweather, then Ryan Clark in his final season. Dashon Goldson followed and Will Blackmon, converted from cornerback, came after him. Which brings the calendar to 2017, the year Swearinger, a Taylor disciple, is playing free safety for the Washington Redskins.

Swearinger bought Taylor’s original number in Washington, 36, for $75,000 from former Redskins player Su’a Cravens back in the spring. Both wanted it to honor Taylor. Cravens, then still in the league on a rookie-level deal, opted for the flood of cash to swap jerseys. Swearinger couldn’t do without the digits.

“It was the only way I could be happy in a Redskins jersey, is if I get a 36,” Swearinger said. “I wouldn’t be happy in a 29, in a 26. It had to be 36 or 21. That’s the only way I’d be happy.”

Count Swearinger, Chancellor and New York’s Landon Collins among those currently in the league who still turn to highlight reels of Taylor to prepare for Sunday.

Chancellor, who grew up in Norfolk, Virginia, was a two-star high school quarterback when Taylor debuted for the Redskins. Eventually, Chancellor was moved to free safety his third season at Virginia Tech. Watching Taylor made Chancellor understand the path for his frame — 6 foot 3, 225 pounds — at the position.

In New York, safety Landon Collins has long idolized Taylor. He keeps pictures of Taylor on his cell phone and wears No. 21 because of him. But, neither Chancellor nor Collins feels the weight of a burgundy No. 36 on their backs, the way Swearinger does.

He began watching Taylor in middle school, honing in on him during the 2003 Fiesta Bowl between Miami and Ohio State. Sundays, or Thursdays, he types “Thuggish Ruggish Bone” and Taylor’s name into YouTube. He knows the highlight video is 3:32. He watches the compilation of Taylor’s playing essence that includes interceptions, pass deflections, and, of course, stout hits, again and again.

“He has so many splash plays and flashy plays, you can’t ignore it,” Swearinger said. “I haven’t seen anybody that does the things that he did down in the box when he was coming down hitting in the box, when he was covering the whole field, scooping up a fumble, taking it to the house, a pick-six to the house, delivering a blow across the middle. Just an all-around game that he had. It was unbelievable. And to be that size was incredible.

“That’s why a lot of guys look to him, because when you put on the tape, that’s what you want to be as a safety. You want to be a guy that puts fear in wide receivers’ hearts, puts fear in the quarterbacks — he knows he can’t throw the ball deep and just put air up under it — running backs coming across the middle. Once they get through the first level, and knowing where Sean was, you got to know where he’s at because you could get an earhole any time he’s on the field. He’s hitting home when he blitzes. He did everything well and that’s why his legacy lives so long.”

***

Ten years ago, Jackie Taylor was an infant hiding under the sheets with her mom when a band of bungling burglars cost her father his life in the hallway just beyond the bedroom door. October 13, 2017, she stood in front of the crowd at the University of Miami Ring of Honor luncheon, by far the youngest and most diminutive representative of the five players included in the ceremony.

She’s 11 now, and was behind a clear podium to give a 68-second speech about her dad, whom she spent just 18 months with. To her right was Taylor’s Miami Hurricanes jersey in a frame.

“My name is Jackie Taylor, and I am honored to be here to receive this award on behalf of my father, Sean Taylor,” she said. “My dad worked very hard in his life to achieve his dreams. He believed that getting to the next level meant working hard on his game while everyone else was resting. I’m so proud of how hard my father worked to receive this honor. He took a lot of pride in his career as a Hurricane.” She closed by thanking Miami for inducting Taylor into its Ring of Honor, and for the school allowing her to represent him at the ceremony. Substantial applause followed.

“She did an awesome job and she represented well,” Pedro Taylor said. “I know she would love to see her father in life. But, at the same time, there’s nothing you can do.”

Moments like that are why Taylor’s legacy endures. It maintains through his daughter, the players he inspired with explosive hits, the jerseys fans wear, the people who type his name into a search box to again watch him on video.

Another reminder was delivered when Taylor’s No. 21, his number in his final three seasons, was sprayed into the grass outside of FedEx Field on Thursday, two 8-foot-by-8-foot yellow numbers framed in white. The numbers show up annually around this time of year, a specifically tricky time for Pedro Taylor. Thanksgiving arrives, with all its reminders of joy, giving, and, of course, football. It’s also a celebration just days away from Nov. 27, a time, even 10 years later, that is still hard to manage.

“You can tell, when I talk I get emotional,” Pedro Taylor said when asked what this part of the calendar is like for him. “…I don’t know…. It’s an emotional time. I never want to see another young man go through the same thing.”

• Todd Dybas can be reached at tdybas@washingtontimes.com.

Please read our comment policy before commenting.