Charles Werth was nearing the end of his first three-year term as an adviser to the Environmental Protection Agency, and had hopes of being kept on for another stint under President Trump.

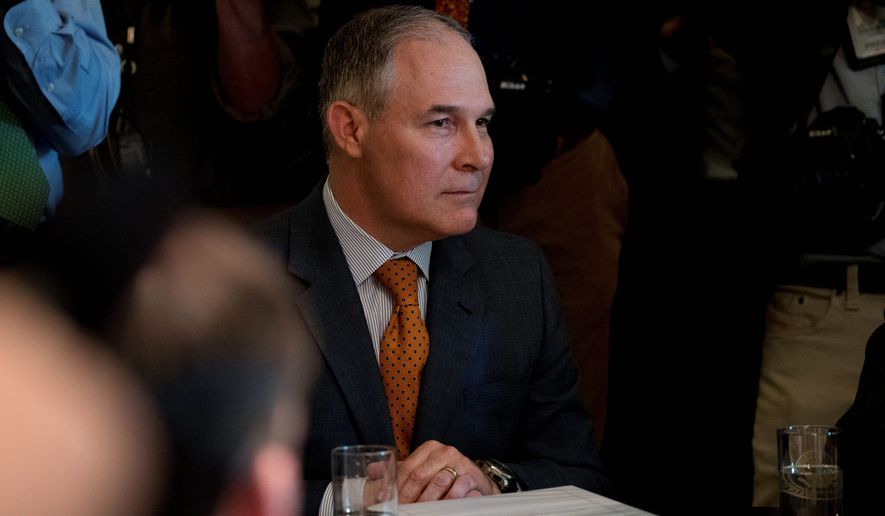

But the University of Texas professor also recently used federal grant money to study drinking water treatment. That, he said, seemed to be enough to sink his chances at another term on the Scientific Advisory Board, after EPA Administrator Scott Pruitt said anyone taking agency money couldn’t also be advising.

“I knew Pruitt had wanted more industrial representation on the board, and my first three-year term was ending,” Mr. Werth told the Washington Times. EPA officials said “they were re-upping me, nominating me for a second three-year term. But I knew there were signs it wouldn’t go through.”

Mr. Werth is one of dozens of professors and researchers who were either kicked off EPA panels or who didn’t get new terms under Mr. Pruitt, and many of them are victims of the new grant money rule.

In many cases, their work for the EPA had little or nothing to do with the research they were conducting at their universities, but the Trump administration’s blanket ban bars anyone who’s using federal grants, regardless of how the money is spent.

For some members, they got virtually no warning, learning of their dismissal just as Mr. Pruitt announced the sweeping change Oct. 31.

“I found out about it right when the press release came out,” Mr. Pruitt said.

Mr. Pruitt and his supporters say the move will help prevent any conflicts of interest on the committees, which review agency-produced science and act as something of a top-level peer-review system before the federal government proposes new regulations, adjusts existing ones, or scraps rules.

“Whatever science comes out of EPA shouldn’t be political science,” the administrator said late last month. “From this day forward, EPA advisory committee members will be financially independent from the agency.”

The policy is the latest example of how Mr. Pruitt, the former attorney general of Oklahoma who had battled the agency throughout the Obama era, intends to reshape the research community’s relationship with the EPA.

The agency says that over the last three years, members of the three EPA boards — the Scientific Advisory Board, the Clean Air Scientific Advisory Committee and the Board of Scientific Counselors — had gotten at least $77 million in grant funding while serving on those panels.

But former members of the committee say it’s simply false to argue that somehow their government-funded research would have an impact on the work they did for the agency.

Not only do they say that they have the most knowledge of the subject matters at hand, they also contend that the EPA is in no way bound by the research they provide, and in the end can make whatever regulatory decisions they want.

“I don’t think it makes sense to exclude the people who know the most about what the EPA is doing,” said Robyn Wilson, a professor of risk analysis and decision science at Ohio State University. “What the EPA decides to do has no bearing on what I do as a researcher There’s no gravy train where the EPA is providing lavish vacations for scientists. It’s funny to me they’re willing to make this trade off, excluding people with legitimate expertise.”

Ms. Wilson, who said she learned she was about to be removed from the Scientific Advisory Board after getting a phone call from a reporter, had been part of a $750,000 EPA-funded grant program studying Great Lakes restoration. About $150,000 of that, she said, was coming to her team at Ohio State.

She was in the second year of her first three-year term when she was removed.

Critics of the change say the EPA already has in place strict rules for ensuring there are no conflicts of interest facing researchers, and that there was no real danger of scientists somehow producing flawed studies simply because they get taxpayer funding.

“All EPA grant applicants must formally declare that there is no conflict of interest posed by receiving such awards,” Chris McEntee, executive director of the American Geophysical Union, said after the announcement.

Mr. Pruitt’s supporters have a much different view.

“When science advisers are receiving millions of dollars from the very agency they are influencing, serious concerns are raised about the independence of those scientists and call into question the integrity of the process as a whole,” said Sen. Jim Inhofe, Oklahoma Republican.

Days after announcing the change, Mr. Pruitt appointed a host of new members to the three panels, including state regulators and representatives from energy giants such as Phillip 66 and Covanta Energy. Professors, researchers and even members of green groups such as the Environmental Defense Fund also remain on the boards.

In total, the Scientific Advisory Board will have 18 new members out of 44 spots; the Clean Air panel had three new appointments of its seven-member body; and the Board of Scientific Counselors has 45 new appointments out of 83 slots, according to the EPA. At least two board members chose to stay on as advisers by disassociating themselves with federal grant funding, the agency said.

• Ben Wolfgang can be reached at bwolfgang@washingtontimes.com.

Please read our comment policy before commenting.