OPINION:

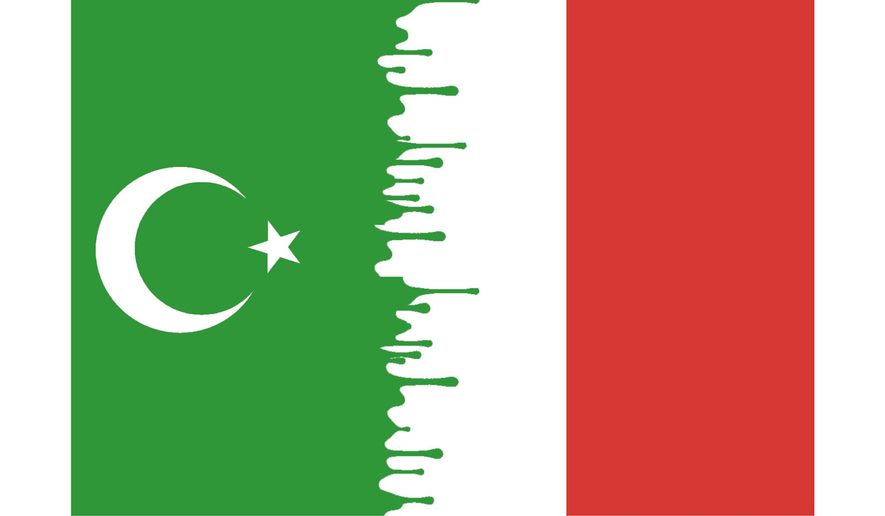

ROME | When thinking about migrants and Islam, Italy is not a country that comes to mind.

Unlike its northern neighbors, Italy had no economic miracle that required the massive importation of labor. It lacks a deep bond to some major source of migration, such as South Asia for Great Britain. It has not experienced major acts of jihadi violence such as France has. Unlike Sweden, one does not hear tales of crazy appeasement and unlike Belgium, there are no partial no-go zones. Unlike the Netherlands, no flamboyant anti-Islamic politician has emerged comparable to Geert Wilders and unlike Germany, no anti-immigration party has become a significant political force.

But, no less than its northern counterparts, Italy deserves attention, for it is undergoing massive changes. Arguably, they are even more pressing, far-reaching and denied more than in the better-known countries.

For starters, there’s geography. Not only does Italy’s famous boot stick prominently into the Mediterranean Sea, making the country a tempting target for seaborne illegal migrants, but Italian territory reaches into North Africa: The small island of Lampedusa, population 6,000, lies just 70 miles off the coast of Tunisia and 184 miles from Libya. In 2016, 181,000 migrants entered Italy, nearly all of them illegal, nearly all by sea.

It was challenge enough when Libya’s Moammar Gadhafi turned the migrant flow on and off, thereby winning concessions from Italy in a game that anticipated what Turkey’s Recep Tayyip Erdogan now plays with Germany. But since Gadhafi’s overthrow in October 2011, the anarchy in Libya presents even greater problems. At least Gadhafi could efficiently be paid off; how much more difficult to deal with a myriad of local strongmen and people-smugglers.

Exacerbating the trend toward what the French intellectual Renaud Camus calls a grand replacement of populations, 285,000 Italians left their homeland in 2016, a major increase over prior years.

Then there’s history. The Muslim presence in Sicily lasted nearly five centuries, 827-1300, and although less celebrated than Andalusia, Islamists remember that era and want Sicily back. Rome, the seat of the Catholic Church, represents a paramount symbol of Islamist ire and ambition, making it highly likely to be a target of jihadi violence.

Demographic trends are even worse than in northern Europe, with a Total Fertility Rate (the number of children per woman) of 1.3, well below that of neighboring France (2.0). Journalist Giulio Meotti tells me that the migrant TFR is almost 2.0 and the indigenous Italian is about 0.9. Some small towns face extinction; One of them, Candela, which has seen its population shrink from 8,000 in the 1990s to 2,700 today, has responded by offering cold cash to induce economically productive immigrants to settle there. Italy’s health minister, Beatrice Lorenzin, has called the demographic trend “an apocalypse.”

In combination, these factors spell a civilizational crisis for Italy. But the wall of denial is close to complete. Yes, the Northern League and the Five-Star Movement oppose unfettered immigration, but this is not their focus. However lopsided and dismissive the debate about immigration and Islamism in the north, it is yet worse in Italy. Voices that confronted these issues a decade ago, such as Magdi Allam, Oriana Fallaci, Fiamma Nirenstein, Emanuele Ottolenghi, and Marcello Pera, no longer resonate. Denial prevails.

Pope Francis has established himself as a leading advocate of unimpeded migration and the uncritical welcoming of migrants, rendering more difficult a critical discussion of this issue. Adding to the political drift, the clueless government of Prime Minister Paolo Gentiloni promotes standard left-wing bromides, barely acknowledging the tectonic shift now underway.

After traveling to 12 cities and towns in Italy, I came away with the impression that the crisis is just too awful for most Italians to cope with. (American readers might compare this to their countrymen’s reluctance to confront the threat of electromagnetic pulse.) A vignette captured the new Italy for me in a park in Padua: A statue is surrounded by four benches. Seven elderly Italian women squeeze onto one bench while eight African men spread out on the other three benches. This scene summed up both mutual distaste and the migrants’ abundant sense of superiority.

What will it take for Italians to wake up and begin to deal with the demographic and civilizational catastrophe facing their uniquely attractive culture? My guess: A major jihadi attack in Rome.

• Daniel Pipes is president of the Middle East Forum.

Please read our comment policy before commenting.